arxiv_id

stringlengths 11

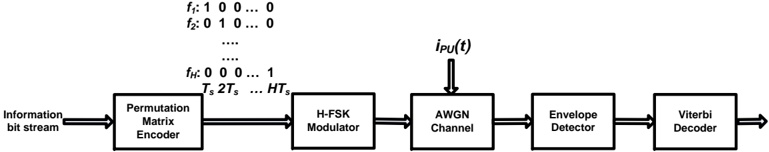

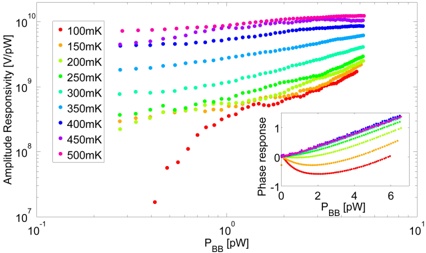

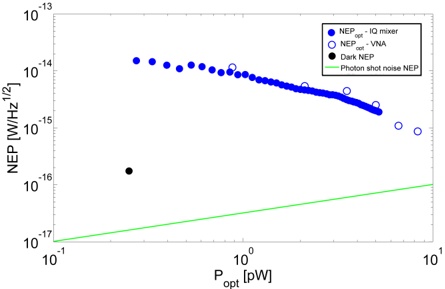

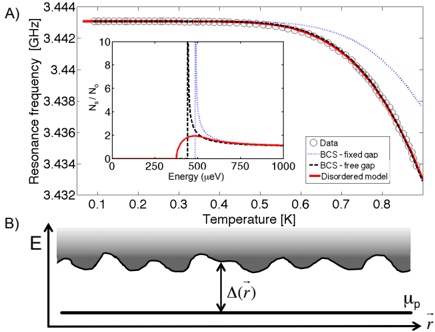

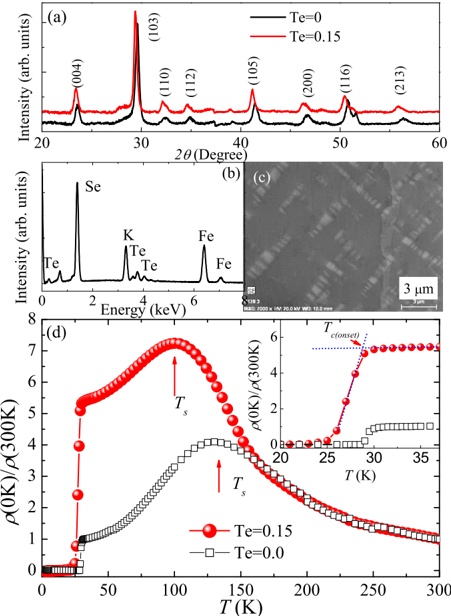

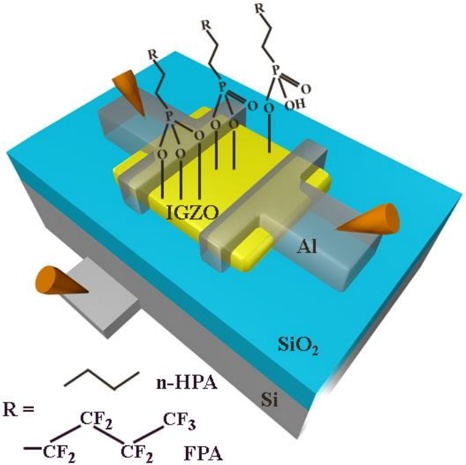

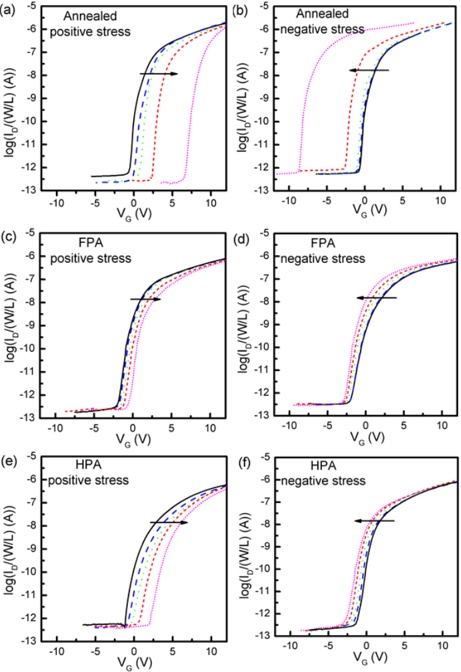

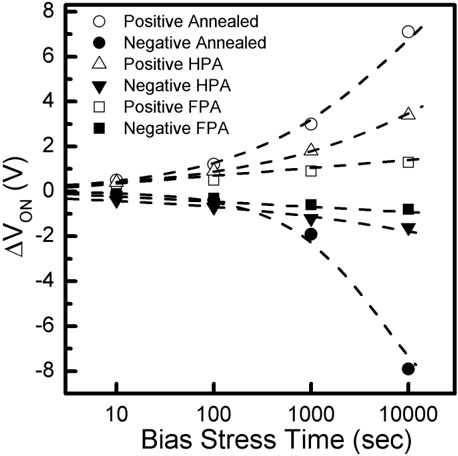

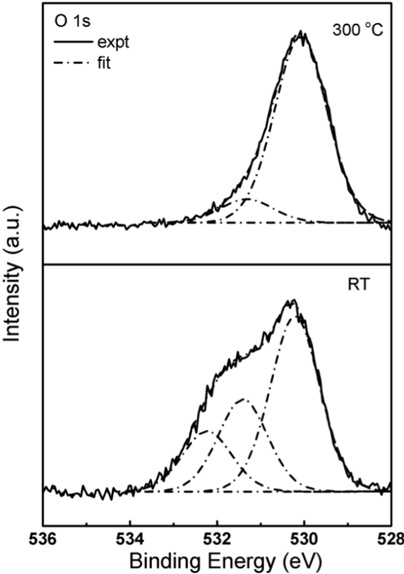

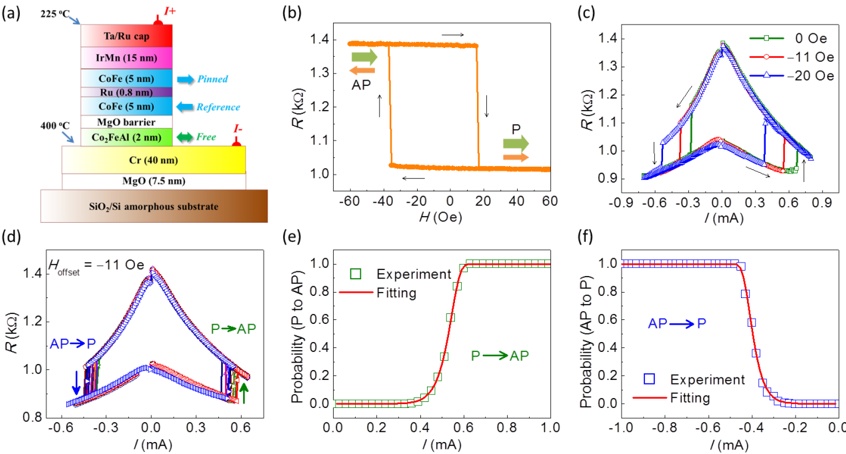

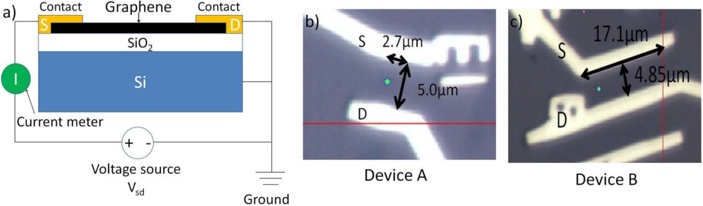

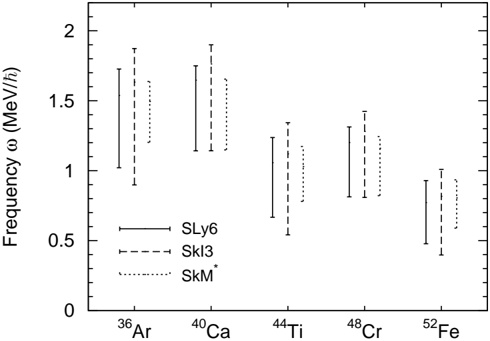

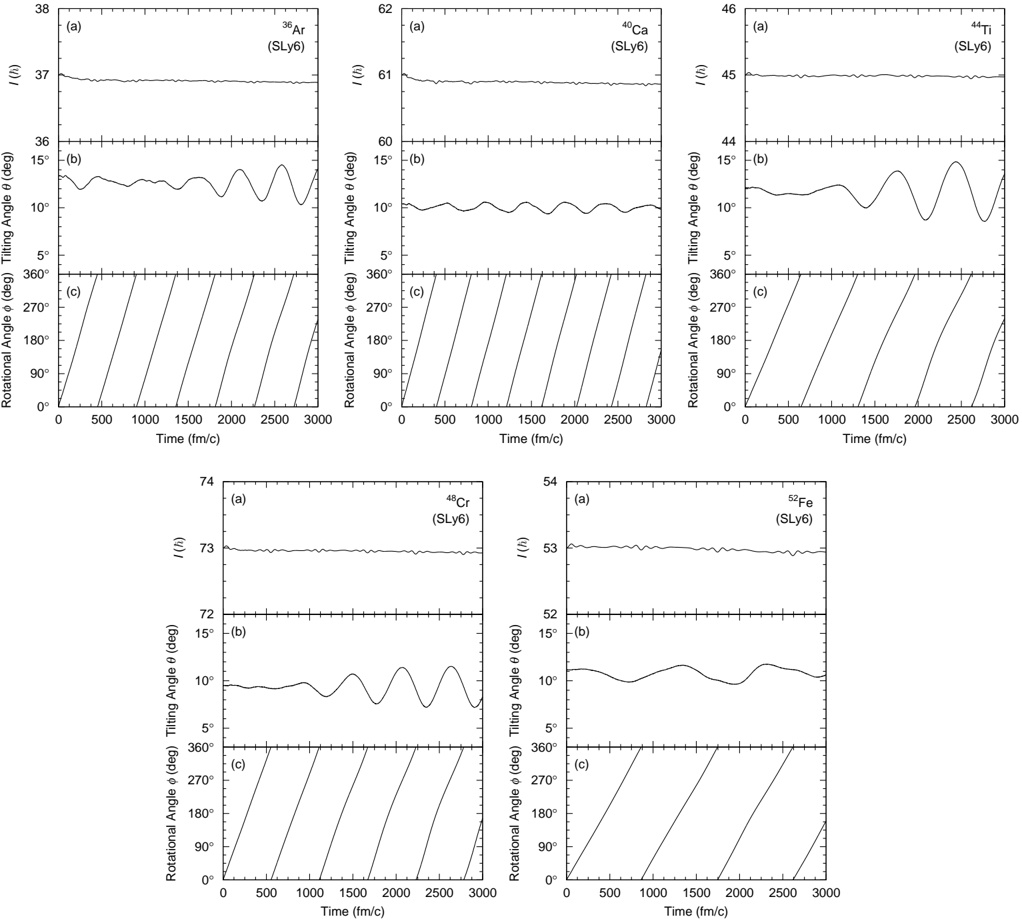

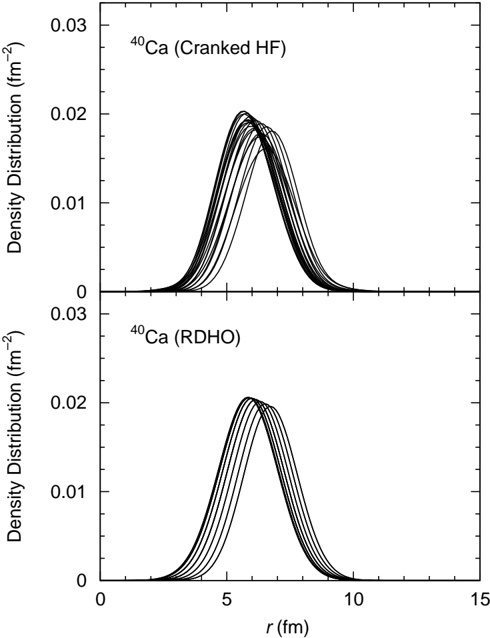

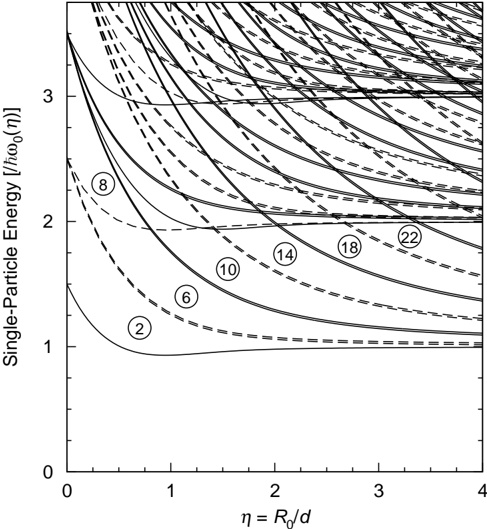

13

| markdown

stringlengths 2.09k

423k

| paper_doi

stringlengths 13

47

⌀ | paper_authors

sequencelengths 1

1.37k

| paper_published_date

stringdate 2014-06-03 19:36:41

2024-08-02 10:23:00

| paper_updated_date

stringdate 2014-06-27 01:00:59

2025-04-23 08:12:32

| categories

sequencelengths 1

7

| title

stringlengths 16

236

| summary

stringlengths 57

2.54k

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1408.0238v1 | ## On the Second Approximate Matsumoto Metric

A. Tayebi, T. Tabatabaeifar and E. Peyghan

August 4, 2014

## Abstract

In this paper, we study the second approximate Matsumoto metric F = α + β + β /α 2 + β /α 3 2 on a manifold M . We prove that F is of scalar flag curvature and isotropic S-curvature if and only if it is isotropic Berwald metric with almost isotropic flag curvature.

Keywords : Isotropic Berwald curvature, S-curvature, almost isotropic flag curvature. 1

## 1 Introduction

The flag curvature in Finsler geometry is a natural extension of the sectional curvature in Riemannian geometry, which is first introduced by L. Berwald. For a Finsler manifold ( M,F ), the flag curvature is a function K ( P, y ) of tangent planes P ⊂ T M x and directions y ∈ P . F is said to be of scalar flag curvature if the flag curvature K ( P, y ) = K ( x, y ) is independent of flags P associated with any fixed flagpole y . F is called of almost isotropic flag curvature if

$$\mathbf K = \frac { 3 c _ { x ^ { m } } y ^ { m } } { F } + \sigma,$$

where c = c x ( ) and σ = σ x ( ) are scalar functions on M . One of the important problems in Finsler geometry is to characterize Finsler manifolds of almost isotropic flag curvature [11].

To study the geometric properties of a Finsler metric, one also considers non-Riemannian quantities. In Finsler geometry, there are several important non-Riemannian quantities: the Cartan torsion C , the Berwald curvature B , the mean Landsberg curvature J and S-curvature S , etc [6][9][11][18]. These are geometric quantities which vanish for Riemnnian metrics.

Among the non-Riemannian quantities, the S-curvature S = S ( x, y ) is closely related to the flag curvature which constructed by Shen for given comparison theorems on Finsler manifolds. A Finsler metric F is called of isotropic S -curvature if

$$\mathbf S = ( n + 1 ) c F,$$

1 2010 Mathematics subject Classification: 53C60, 53C25.

for some scalar function c = c x ( ) on M . In [11], it is proved that if a Finsler metric F of scalar flag curvature is of isotropic S-curvature (2), then it has almost isotropic flag curvature (1).

The geodesic curves of a Finsler metric F = F x, y ( ) on a smooth manifold M , are determined by ¨ c i +2 G c i ( ˙) = 0, where the local functions G i = G x,y i ( ) are called the spray coefficients. A Finsler metric F is called a Berwald metric, if G i are quadratic in y ∈ T M x for any x ∈ M . A Finsler metric F is said to be isotropic Berwald metric if its Berwald curvature is in the following form

$$B ^ { i } _ { \ j k l } = c \Big \{ F _ { y ^ { j } y ^ { k } } \delta ^ { i } _ { \ l } + F _ { y ^ { k } y ^ { l } } \delta ^ { i } _ { \ j } + F _ { y ^ { l } y ^ { j } } \delta ^ { i } _ { \ k } + F _ { y ^ { j } y ^ { k } y ^ { l } } y ^ { i } \Big \}, \quad \quad ( 3 ) \\ \text{where } c = c ( x ) \text{ is a scalar function on } M \ [ 6 ].$$

where c = ( ) is a scalar function on c x M [6].

As a generalization of Berwald curvature, B´cs´-Matsumoto proposed the a o notion of Douglas curvature [1]. A Finsler metric is called a Douglas metric if G i = 1 2 Γ i jk ( x y y ) j k + P x, y y ( ) i .

In order to find explicit examples of Douglas metrics, we consider ( α, β )-metrics. An ( α, β )-metric is a Finsler metric of the form F := αφ ( β α ), where φ = φ s ( ) is a C ∞ on ( -b 0 , b 0 ) with certain regularity, α = √ a ij ( x y y ) i j is a Riemannian metric and β = b i ( x y ) i is a 1-form on M . This class of metrics is were first introduced by Matsumoto [10]. Among the ( α, β )-metrics, the Matsumoto metric is special and significant metric which constitute a majority of actual research. The Matsumoto metric is expressed as

$$F = \alpha & \left [ 1 + \frac { \beta } { \alpha } + ( \frac { \beta } { \alpha } ) ^ { 2 } + ( \frac { \beta } { \alpha } ) ^ { 3 } + \cdots \right ]. \\ \text{as introduced by Matsumoto as a realization of}$$

This metric was introduced by Matsumoto as a realization of Finsler's idea 'a slope measure of a mountain with respect to a time measure' [19]. In the Matsumoto metric, the 1-form β = b y i i was originally to be induced by earth gravity. Hence, we could regard b i ( x ) as the the infinitesimals and neglect the infinitesimals of degree of b i ( x ) more than two [12][13][14][15][16]. An approximate Matsumoto metric is a Finsler metric in the following form

$$F = \alpha \left [ \sum _ { k = 0 } ^ { r } ( \frac { \beta } { \alpha } ) ^ { k } \right ], \\ \text{more information see [13]} \text{ \ This metric was introduced}$$

where | β | < α | | (for more information, see [13]). This metric was introduced by Park-Choi in [13]. By definition, the Matsumoto metric is expressed as lim r →∞ L α, β ( ) = α 2 α -β .

In this paper, we consider second approximate Matsumoto metric F = α + β + β 2 α + β 3 α 2 with some non-Riemannian curvature properties and prove the following.

Theorem 1.1. Let F = α + β + β 2 α + β 3 α 2 be a non-Riemannian second approximate Matsumoto metric on a manifold M of dimension n . Then F is of scaler flag curvature with isotropic S -curvature (2), if and only if it has isotropic Berwald curvature (3) with almost isotropic flag curvature (1). In this case, F must be locally Minkowskian.

## 2 Preliminaries

Let M be a n-dimensional C ∞ manifold. Denote by T M x the tangent space at x ∈ M , by TM = ∪ x ∈ M x T M the tangent bundle of M , and by TM 0 = TM \ { 0 } the slit tangent bundle on M . A Finsler metric on M is a function F : TM → [0 , ∞ ) which has the following properties: (i) F is C ∞ on TM 0 ;

- (ii) F is positively 1-homogeneous on the fibers of tangent bundle TM ;

- (iii) for each y ∈ T M x , the following quadratic form g y on T M x is positive definite,

$$\mathbf g _ { y } ( u, v ) \coloneqq \frac { 1 } { 2 } \frac { \partial ^ { 2 } } { \partial s \partial t } \left [ F ^ { 2 } ( y + s u + t v ) \right ] | _ { s, t = 0 }, \ u, v \in T _ { x } M. \\ \text{et } x \in M \text{ and } F _ { x } \coloneqq F | _ { T _ { x } M }. \text{ To measure the non-Euclidean feature of } F _ { x }$$

Let x ∈ M and F x := F | T M x . To measure the non-Euclidean feature of F x , define C y : T M x ⊗ T M x ⊗ T M x → R by

$$\mathbf C _ { y } ( u, v, w ) \coloneqq \frac { 1 } { 2 } \frac { d } { d t } \left [ \mathbf g _ { y + t w } ( u, v ) \right ] | _ { t = 0 }, \ u, v, w \in T _ { x } M. \\ \intertext { a l m v \, } \mathbf C \coloneqq \{ \mathbf C _ { x } \} _ { \sim \mathbf T _ { M } } \text{ is called the Cartan torsion. It is well known } t$$

The family C := { C y } y ∈ TM 0 is called the Cartan torsion. It is well known that C = 0 if and only if F is Riemannian [17]. For y ∈ T M x 0 , define mean Cartan torsion I y by I y ( u ) := I i ( y u ) i , where I i := g jk C ijk . By Diecke Theorem, F is Riemannian if and only if I y = 0.

The horizontal covariant derivatives of I along geodesics give rise to the mean Landsberg curvature J y ( u ) := J i ( y u ) i , where J i := I i s | y s . A Finsler metric is said to be weakly Landsbergian if J = 0.

Given a Finsler manifold ( M,F ), then a global vector field G is induced by F on TM 0 , which in a standard coordinate ( x , y i i ) for TM 0 is given by G = y i ∂ ∂x i -2 G x,y i ( ) ∂ ∂y i , where

$$G ^ { i } \coloneqq \frac { 1 } { 4 } g ^ { i l } \left [ \frac { \partial ^ { 2 } ( F ^ { 2 } ) } { \partial x ^ { k } \partial y ^ { l } } y ^ { k } - \frac { \partial ( F ^ { 2 } ) } { \partial x ^ { l } } \right ], \quad y \in T _ { x } M. \\ \text{-} \text{-} \text{allad to an even a-occuritized $t_{\mathbb{ }T}_{M}_{F}\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb { }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{t_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathBB{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T$_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathfrak{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T _\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb

}T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{ \mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{

}T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T _$_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\tilde{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T._\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{\ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{ \mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb`T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{ }T_{\mathbb{$$

The G is called the spray associated to ( M,F ). In local coordinates, a curve c t ( ) is a geodesic if and only if its coordinates ( c i ( )) satisfy ¨ t c i +2 G c i ( ˙) = 0.

For a tangent vector y ∈ T M x 0 , define B y : T M x ⊗ T M x ⊗ T M x → T M x and E y : T M x ⊗ T M x → R by B y ( u, v, w ) := B i jkl ( y u v ) j k w l ∂ ∂x i | x and E y ( u, v ) := E jk ( y u v ) j k where

$$B ^ { i } _ { \ j k l } \coloneqq \frac { \partial ^ { 3 } G ^ { i } } { \partial y ^ { j } \partial y ^ { k } \partial y ^ { l } }, \ \ E _ { j k } \coloneqq \frac { 1 } { 2 } B ^ { m } _ { \ j k m }.$$

The B and E are called the Berwald curvature and mean Berwald curvature, respectively. Then F is called a Berwald metric and weakly Berwald metric if B = 0 and E = 0 , respectively.

A Finsler metric F is said to be isotropic mean Berwald metric if its mean Berwald curvature is in the following form

$$E _ { i j } = \frac { n + 1 } { 2 F } c h _ { i j }, \quad \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \

\quad. \quad.$$

where c = ( ) is a scalar function on c x M and h ij is the angular metric [6].

Define D y : T M x ⊗ T M x ⊗ T M x → T M x by D y ( u, v, w ) := D i jkl ( y u v ) i j w k ∂ ∂x i | x where

$$\ v n e r e \quad & D ^ { i } _ { \ j k l } \coloneqq B ^ { i } _ { \ j k l } - \frac { 2 } { n + 1 } \{ E _ { j k } \delta ^ { i } _ { l } + E _ { j l } \delta ^ { i } _ { k } + E _ { k l } \delta ^ { i } _ { j } + E _ { j k, l } y ^ { i } \}. \\ \cdots \quad \cdots \quad \cdots \quad \cdots \quad \cdots \quad.$$

We call D := { D y } y ∈ TM 0 the Douglas curvature. A Finsler metric with D = 0 is called a Douglas metric. The notion of Douglas metrics was proposed by B´cs´-Matsumoto as a generalization of Berwald metrics [1]. a o

For a Finsler metric F on an n -dimensional manifold M , the BusemannHausdorff volume form dV F = σ F ( x dx ) 1 · · · dx n is defined by

∣ In general, the local scalar function σ F ( x ) can not be expressed in terms of elementary functions, even F is locally expressed by elementary functions. Let G i denote the geodesic coefficients of F in the same local coordinate system. The S-curvature can be defined by

$$\cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdot \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \colon \\ \sigma _ { F } ( x ) \coloneqq \frac { \text{Vol} ( \mathbb { B } ^ { n } ( 1 ) ) } { \text{Vol} \left \{ ( y ^ { i } ) \in R ^ { n } \, \Big | \ F \left ( y ^ { i } \frac { \partial } { \partial x ^ { i } } | _ { x } \right ) < 1 \right \} \\ \text{al, the local scalar function $\sigma_{F} ( x ) \, \text{ can not be expressed in}$} \\ \text{ry functions, even $F$ is locally expressed by elementary funct}$$

$$\mathbf S ( \mathbf y ) \coloneqq \frac { \partial G ^ { i } } { \partial y ^ { i } } ( x, y ) - y ^ { i } \frac { \partial } { \partial x ^ { i } } \left [ \ln \sigma _ { F } ( x ) \right ], \\ \frac { \partial } { \partial x } | _ { x } \in T _ { r } M. \text{ It is proved that } \mathbf S = 0 \text{ if } F \text{ is a Be}$$

where y = y i ∂ ∂x i | x ∈ T M x . It is proved that S = 0 if F is a Berwald metric. There are many non-Berwald metrics satisfying S = 0. S said to be isotropic if there is a scalar functions c x ( ) on M such that S = ( n +1) ( c x F ) .

The Riemann curvature R y = R i k dx k ⊗ ∂ ∂x i | x : T M x → T M x is a family of linear maps on tangent spaces, defined by

$$R ^ { i } _ { \ k } = 2 \frac { \partial G ^ { i } } { \partial x ^ { k } } - y ^ { j } \frac { \partial ^ { 2 } G ^ { i } } { \partial x ^ { j } \partial y ^ { k } } + 2 G ^ { j } \frac { \partial ^ { 2 } G ^ { i } } { \partial y ^ { j } \partial y ^ { k } } - \frac { \partial G ^ { i } } { \partial y ^ { j } } \frac { \partial G ^ { j } } { \partial y ^ { k } }.$$

For a flag P = span { y, u } ⊂ T M x with flagpole y , the flag curvature K = K ( P, y ) is defined by

$$\mathbf K ( P, y ) \coloneqq \frac { \mathbf g _ { y } ( u, \mathbf R _ { y } ( u ) ) } { \mathbf g _ { y } ( y, y ) \mathbf g _ { y } ( u, u ) - \mathbf g _ { y } ( y, u ) ^ { 2 } }. \\ \text{a Finsler metric $F$ is of scalar curvature if for any $u$}$$

We say that a Finsler metric F is of scalar curvature if for any y ∈ T M x , the flag curvature K = K ( x, y ) is a scalar function on the slit tangent bundle TM 0 . In this case, for some scalar function K on TM 0 the Riemann curvature is in the following form

$$R ^ { i } _ { \ k } = \mathbf K F ^ { 2 } \{ \delta ^ { i } _ { k } - F ^ { - 1 } F _ { y ^ { k } } y ^ { i } \}. \\ \text{hon } F \text{ is said to be of content } \text{a} \, \text{a} \, \text{$c}$$

If K = constant , then F is said to be of constant flag curvature. A Finsler metric F is called isotropic flag curvature , if K = K ( x ).

## 3 Proof of Theorem 1.1

Let F = αφ s ( ), s = β α be an ( α, β )-metric, where φ = φ s ( ) is a C ∞ on ( -b 0 , b 0 ) with certain regularity, α = √ a ij ( x y y ) i j is a Riemannian metric and β = b i ( x y ) i is a 1-form on a manifold M . Let

$$r _ { i j } \coloneqq \frac { 1 } { 2 } \left [ b _ { i | j } + b _ { j | i } \right ], \quad s _ { i j } \coloneqq \frac { 1 } { 2 } \left [ b _ { i | j } - b _ { j | i } \right ]. \\ r _ { j } \coloneqq b ^ { i } r _ { i j }, \quad s _ { j } \coloneqq b ^ { i } s _ { i j }. \\ \quad \,.$$

where b i j | denote the coefficients of the covariant derivative of β with respect to α . Let

$$r _ { i 0 } \coloneqq r _ { i j } y ^ { j }, \ s _ { i 0 } \coloneqq s _ { i j } y ^ { j }, \ r _ { 0 } \coloneqq r _ { j } y ^ { j }, \ s _ { 0 } \coloneqq s _ { j } y ^ { j }.$$

Put

$$Q & = \frac { \phi ^ { \prime } } { \phi - s \phi }, \\ \Theta & = \frac { \phi \phi ^ { \prime } - s ( \phi \phi ^ { \prime \prime } + \phi ^ { \prime 2 } ) } { 2 \phi \left [ ( \phi - s \phi ^ { \prime } ) + ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ) \phi ^ { \prime \prime } \right ] } \\ \Psi & = \frac { \phi ^ { \prime \prime } } { 2 \left [ ( \phi - s \phi ^ { \prime } ) + ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ) \phi ^ { \prime \prime } \right ] }. \\ \text{urvature is given by} \\ \prime \quad \underset { \theta } { \sim } \cap \quad \ \overline { \nu } \cap \overline { \nu } \cap \ \overline { \nu } \cap \ \overline { \nu } \end{pmatrix}$$

Then the S -curvature is given by

$$\mathbf S = \left [ Q ^ { \prime } - 2 \Psi Q s & - \ 2 ( \Psi Q ) ^ { \prime } ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ) - 2 ( n + 1 ) Q \Theta + 2 \lambda \right ] s _ { 0 } \\ & + \ 2 ( \Psi + \lambda ) s _ { 0 } + \alpha ^ { - 1 } \left [ ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ) \Psi ^ { \prime } + ( n + 1 ) \Theta \right ] r _ { 0 0 }. \\ \text{Let us put}$$

Let us put

$$\Delta & \coloneqq \ 1 + s Q + ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ) Q ^ { \prime }, \\ \Phi & \coloneqq \ - ( n \Delta + 1 + s Q ) ( Q - s Q ^ { \prime } ) - ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ) ( 1 + s Q ) Q ^ { \prime \prime }. \\ \vdots \sim \sim \ \sim \ \sim \ \cdot \quad \cdot \quad \cdot \quad \cdot \quad \cdot \quad \cdot \quad \cdot \quad \cdot \quad \cdot$$

In [5], Cheng-Shen characterize ( α, β )-metrics with isotropic S-curvature.

Lemma 3.1. ([5]) Let F = αφ β/α ( ) be an ( α, β )-metric on an n -manifold. Then, F is of isotropic S-curvature S = ( n + 1) cF , if and only if one of the following holds

## (i) β satisfies

$$r _ { i j } = \varepsilon \left \{ b ^ { 2 } a _ { i j } - b _ { i } b _ { j } \right \}, \quad s _ { j } = 0, & & ( 8 ) \\ x ) \text{ is a scalar function, and } \phi = \phi ( s ) \text{ satisfies}$$

where ε = ( ) is a scalar function, and ε x φ = φ s ( ) satisfies

$$\Phi = - 2 ( n + 1 ) k \frac { \phi \Delta ^ { 2 } } { b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } }, \\ \prod _ { \text{out in to each } } \varepsilon = \iota _ { \varepsilon }$$

where k is a constant. In this case, c = k/epsilon1 .

(ii) β satisfies

In this case, c = 0.

Let

$$\Psi _ { 1 } \, \coloneqq \, & \sqrt { b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } } \Delta ^ { \frac { 1 } { 2 } } \left [ \frac { \sqrt { b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } } \Phi } { \Delta ^ { \frac { 3 } { 2 } } } \right ] ^ { \prime }, \\ \Psi _ { 2 } \, \coloneqq \, & 2 ( n + 1 ) ( Q - s Q ^ { \prime } ) + 3 \frac { \Phi } { \Delta }, \\ \theta \, \coloneqq \, & \frac { Q - s Q ^ { \prime } } { 2 \Delta }. \\ \text{rmula for the mean Cartan torsion of an } ( \alpha, \beta ) \text{-metric is given by}$$

Then the formula for the mean Cartan torsion of an ( α, β )-metric is given by following

$$I _ { i } & = \frac { 1 } { 2 } \frac { \partial } { \partial y ^ { i } } \left [ ( n + 1 ) \frac { \phi ^ { \prime } } { \phi } - ( n - 2 ) \frac { s \phi ^ { \prime \prime } } { \phi - s \phi ^ { \prime } } - \frac { 3 s \phi ^ { \prime \prime } - ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ) \phi ^ { \prime \prime \prime } } { ( \phi - s \phi ^ { \prime } ) + ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ) \phi ^ { \prime \prime } } \right ] \\ & = - \frac { \Phi ( \phi - s \phi ^ { \prime } ) } { 2 \Delta \phi \alpha ^ { 2 } } ( \alpha b _ { i } - s y _ { i } ). \\ \vdots \, \vdots \, \vdots \, \dots \, \dots \, \vdots \, \vdots \, \vdots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \vdots \, \vdots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \vdots \, \vdots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \vdots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \vdots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \dots \, \end{array}$$

In [7], it is proved that the condition Φ = 0 characterizes the Riemannian metrics among ( α, β )-metrics. Hence, in the continue, we suppose that Φ = 0.

/negationslash

Let G i = G x,y i ( ) and ¯ G i α = ¯ G i α ( x, y ) denote the coefficients of F and α respectively in the same coordinate system. By definition, we have

$$G ^ { i } = \bar { G } _ { \alpha } ^ { i } + P y ^ { i } + Q ^ { i },$$

where

$$P \coloneqq \ \alpha ^ { - 1 } \Theta \Big [ - 2 Q \alpha s _ { 0 } + r _ { 0 0 } \Big ] \\ Q ^ { i } \coloneqq \ \alpha Q s ^ { i } _ { 0 } + \Psi \Big [ - 2 Q \alpha s _ { 0 } + r _ { 0 0 } \Big ] b ^ { i }. \\ \text{ yields the following}$$

Simplifying (13) yields the following

$$G ^ { i } = \bar { G } _ { \alpha } ^ { i } + \alpha Q s _ { 0 } ^ { i } + \theta ( - 2 \alpha Q s _ { 0 } + r _ { 0 0 } ) \left [ \frac { y ^ { i } } { \alpha } + \frac { Q ^ { \prime } } { Q - s Q ^ { \prime } } b ^ { i } \right ]. \quad \ ( 1 4 ) \\ \text{Clearly, if } \beta \text{ is parallel with respect to } \alpha \ ( r _ { i j } = 0 \text{ and } s _ { i j } = 0 ), \text{ then } P = 0 \text{ and }$$

Clearly, if β is parallel with respect to α ( r ij = 0 and s ij = 0), then P = 0 and Q i = 0. In this case, G i = ¯ G i α are quadratic in y , and F is a Berwald metric.

For an ( α, β )-metric F = αφ s ( ), the mean Landsberg curvature is given by

$$& \text{For an } ( \alpha, \beta ) \text{-metric } F = \alpha \phi ( s ), \text{ the mean Landsberg curvature is given by} \\ J _ { i } = & \ - \frac { 1 } { 2 \Delta \alpha ^ { 4 } } \left [ \frac { 2 \alpha ^ { 2 } } { b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } } [ \frac { \Phi } { \Delta } + ( n + 1 ) ( Q - s Q ^ { \prime } ) ] ( r _ { 0 } + s _ { 0 } ) h _ { i } \\ & \ + \frac { \alpha } { b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } } ( \Psi _ { 1 } + s \frac { \Phi } { \Delta } ) ( r _ { 0 0 } - 2 \alpha Q s _ { 0 } ) h _ { i } + \alpha \left [ - \alpha Q ^ { \prime } s _ { 0 } h _ { i } + \alpha Q ( \alpha ^ { 2 } s _ { i } - y _ { i } s _ { 0 } ) \\ & \ + \alpha ^ { 2 } \Delta s _ { i 0 } + \alpha ^ { 2 } ( r _ { i 0 } - 2 \alpha Q s _ { i } ) - ( r _ { 0 0 } - 2 \alpha Q s _ { 0 } ) y _ { i } \right ] \frac { \Phi } { \Delta } \right ].$$

$$r _ { i j } = 0, \quad s _ { j } = 0.$$

Contracting (15) with b i = a im b m yields

$$\bar { J } \coloneqq J _ { i } b ^ { i } = - \frac { 1 } { 2 \Delta \alpha ^ { 2 } } \left [ \Psi _ { 1 } ( r _ { 0 0 } - 2 \alpha Q s _ { 0 } ) + \alpha \Psi _ { 2 } ( r _ { 0 } + s _ { 0 } ) \right ]. \quad \ ( 1 6 ) \\ \text{The horizontal covariant derivatives } J _ { i ; m } \text{ and } J _ { i | m } \text{ of } J _ { i } \text{ with respect to } F \text{ and}$$

The horizontal covariant derivatives J i m ; and J i m | of J i with respect to F and α , respectively, are given by

$$J _ { i ; m } = \frac { \partial J _ { i } } { \partial x ^ { m } } - J _ { l } \Gamma ^ { l } _ { i m } - \frac { \partial J _ { i } } { \partial y ^ { l } } N ^ { l } _ { m },$$

$$J _ { i | m } = \frac { \partial J _ { i } } { \partial x ^ { m } } - J _ { l } \bar { \Gamma } ^ { l } _ { i m } - \frac { \bar { \partial J _ { i } } } { \partial y ^ { l } } \bar { N } ^ { l } _ { m }.$$

Then we have

$$J _ { i ; m } y ^ { m } = J _ { i | m } y ^ { m } - J _ { l } ( N _ { i } ^ { l } - \bar { N } _ { i } ^ { l } ) - 2 \frac { \partial J _ { i } } { \partial y ^ { l } } ( G ^ { l } - \bar { G } ^ { l } ). \quad \quad ( 1 7 )$$

Let F be a Finsler metric of scalar flag curvature K . By Akbar-Zadeh's theorem it satisfies following

$$A _ { i j k ; s ; m } y ^ { s } y ^ { m } + \mathbf K F ^ { 2 } A _ { i j k } + \frac { F ^ { 2 } } { 3 } \left [ h _ { i j } \mathbf K _ { k } + h _ { j k } \mathbf K _ { j } + h _ { k i } \mathbf K _ { j } \right ] = 0, \quad ( 1 8 ) \\ \text{where } A _ { i j k } = F C _ { i j k } \text{ is the Cartan torsion and } \mathbf K _ { i } = \frac { \partial \mathbf K } { A. i } \, [ 2 ]. \text{ Contracting } ( 1 8 )$$

$$\Phi _ { \Phi _ { i } ; m } y ^ { m } + \mathbf K F ^ { 2 } I _ { i } + \frac { n + 1 } { 3 } F ^ { 2 } \mathbf K _ { i } = 0. \quad \ \quad \ \ ( 1 9 ) \\ \Phi _ { \Phi _ { i } ; m } \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nu \nolimits \Phi _ { \Phi _ { i } } }$$

where A ijk = FC ijk is the Cartan torsion and K i = ∂ K ∂y i [2]. Contracting (18) with g ij yields

By (17) and (19), for an ( α, β )-metric F = αφ s ( ) of constant flag curvature K , the following holds

$$J _ { i | m } - J _ { l } \frac { \partial ( G ^ { l } - \bar { G } ^ { l } ) } { \partial y ^ { i } } b ^ { i } - 2 \frac { \partial \bar { J } } { \partial y ^ { l } } ( G ^ { l } - \bar { G } ^ { l } ) \mathbf K \alpha ^ { 2 } \phi ^ { 2 } I _ { i } = 0. \quad \ ( 2 0 )$$

Contracting (20) with b i implies that

$$\bar { J } _ { | m } y ^ { m } - J _ { i } a ^ { i k } b _ { k | m } y ^ { m } - J _ { l } \frac { \partial ( G ^ { l } - \bar { G } ^ { l } ) } { \partial y ^ { i } } b ^ { i } - 2 \frac { \partial \bar { J } } { \partial y ^ { l } } ( G ^ { l } - \bar { G } ^ { l } ) + \mathbf K \alpha ^ { 2 } \phi ^ { 2 } I _ { i } b ^ { i } = 0. \ ( 2 1 )$$

There exists a relation between mean Berwald curvature E and the Scurvature S . Indeed, taking twice vertical covariant derivatives of the S-curvature gives rise the E -curvature. It is easy to see that, every Finsler metric of isotropic S-curvature (2) is of isotropic mean Berwald curvature (5). Now, is the equation S = ( n +1) cF equivalent to the equation E = n +1 2 cF -1 h ?

/negationslash

Recently, Cheng-Shen prove that a Randers metric F = α + β is of isotropic S -curvature if and only if it is of isotropic E -curvature [4]. Then, Chun-HuanCheng extend this equivalency to the Finsler metric F = α -m ( α + β ) m +1 for every real constant m , including Randers metric [3]. In [8], Cui extend their result and show that for the Matsumoto metric F = α 2 α -β and the special ( α, β )-metric F = α + /epsilon1β + κ β /α ( 2 ) ( κ = 0), these notions are equivalent.

To prove Theorem 1.1, we need the following.

Proposition 3.2. Let F = α + β + β 2 α + β 3 α 2 be a second approximate Matsumoto metric on a manifold M of dimension n . Then the following are equivalent

- (i) F has isotropic S -curvature, S = ( n +1) ( c x F ) ;

- (ii) F has isotropic mean Berwald curvature, E = n +1 2 c x F ( ) -1 h ;

where c = ( ) c x is a scalar function on the manifold M . In this case, S = 0 . Then β is a Killing 1 -form with constant length with respect to α , that is, r 00 = 0 .

Proof. ( ) i → ( ii ) is obvious. Conversely, suppose that F has isotropic mean Berwald curvature, E = ( n +1) 2 c x F ( ) -1 h . Then we have

$$\mathbf S = ( n + 1 ) [ c F + \eta ],$$

where η = η i ( x y ) i is a 1-form on M . For the second approximate Matsumoto metric, (6) reduces to following

$$\text{etric, (0) requires to following} \\ Q = & - \frac { 1 + 2 s + 3 s ^ { 2 } } { - 1 + s ^ { 2 } + 2 s ^ { 3 } }, \\ \Theta = & \frac { 1 } { 2 } \frac { 1 - 6 s ^ { 2 } - 1 2 s ^ { 3 } - 1 5 s ^ { 4 } - 1 2 s ^ { 5 } } { ( 1 + s + s ^ { 2 } + s ^ { 3 } ) ( 1 - 3 s ^ { 2 } - 8 s ^ { 3 } + 2 b ^ { 2 } + 6 b ^ { 2 } s ) }, \\ \Psi = & \frac { 1 + 3 s } { ( 1 - 3 s ^ { 2 } - 8 s ^ { 3 } + 2 b ^ { 2 } + 6 b ^ { 2 } s ) }. \\ \mu = & \mu \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \colon$$

By substituting (22) and (23) in (7), we have

$$\Psi = & \, \frac { \left ( 1 - 3 s ^ { 2 } - 8 s ^ { 3 } + 2 b ^ { 2 } + 6 b ^ { 2 } s \right ) }. \\ \dots & \, \left ( \infty \, \cdots \, \cdots \, \left ( \infty \, \cdots \, \right ) \, \left ( \infty \, \cdots \, \cdots \, \cdots \, \cdots \,.$$

$$& \gamma - ( 1 - 3 s ^ { 2 } - 8 s ^ { 3 } + 2 b ^ { 2 } + 6 b ^ { 2 } s ) ^ { \cdot } \quad \langle \rangle ^ { \cdot \rangle } \\ \text{By substituting} \, ( 2 2 ) \, \text{and} \, ( 2 3 ) \, \text{in} \, ( 7 ), \, \text{we have} \\ \text{S} & = \, \left [ \frac { 2 ( 1 + 3 s ) ( 1 + s + s ^ { 2 } + s ^ { 3 } ) } { ( - 1 + s ^ { 2 } + 2 s ^ { 3 } ) ^ { 2 } } \, + \, ( 1 - 3 s ^ { 2 } - 8 s ^ { 3 } + 2 b ^ { 2 } + 6 b ^ { 2 } s ) ( - 1 + s ^ { 2 } + 2 s ^ { 3 } ) } \\ & \quad - \frac { 2 ( 5 + 2 6 s + 7 7 s ^ { 2 } + 8 8 s ^ { 3 } - 6 1 s ^ { 4 } - 4 3 0 s ^ { 5 } - 8 0 5 s ^ { 6 } + 4 b ^ { 2 } + 4 0 b ^ { 2 } s + 1 4 8 b ^ { 2 } s ) ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ) } { ( 1 - 3 s ^ { 2 } - 8 s ^ { 3 } + 2 b ^ { 2 } + 6 b ^ { 2 } s ) ^ { 2 } ( - 1 + s ^ { 2 } + 2 s ^ { 3 } ) ^ { 2 } } \\ & \quad + \frac { ( n + 1 ) ( 1 + 2 s + 3 s ^ { 2 } ) ( 1 - 6 s ^ { 2 } - 1 2 s ^ { 3 } - 1 5 s ^ { 4 } - 1 2 s ^ { 5 } ) } { ( - 1 + s ^ { 2 } + 2 s ^ { 3 } ) ( 1 + s + s ^ { 2 } + s ^ { 3 } ) ( 1 - 3 s ^ { 2 } - 8 s ^ { 3 } + 2 b ^ { 2 } + 6 b ^ { 2 } s ) } + 2 \lambda \right ] s _ { 0 } \\ & \quad + 2 \left [ \frac { ( 1 + 3 s ) } { 1 - 3 s ^ { 2 } - 8 s ^ { 3 } + 2 b ^ { 2 } + 6 b ^ { 2 } s } \right ] + \frac { ( 1 ) s ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ) ( 1 + 1 s ^ { 2 } + 1 6 s ^ { 3 } + 2 s ) } { \alpha ( 1 - 3 s ^ { 2 } - 8 s ^ { 3 } + 2 b ^ { 2 } + 6 b ^ { 2 } s ) ^ { 2 } } \right ] r _ { 0 0 } \\ & \quad + \left [ \frac { ( n + 1 ) ( 1 - 6 s ^ { 2 } - 1 2 s ^ { 3 } - 1 5 s ^ { 4 } - 1 2 s ^ { 5 } ) } { 2 \alpha ( 1 + s + s ^ { 2 } + s ^ { 3 } ) ( 1 - 3 s ^ { 2 } - 8 s ^ { 3 } + 2 b ^ { 2 } + 6 b ^ { 2 } s ) } \right ] r _ { 0 0 } \\ & = \, ( n + 1 ) \left [ \alpha ( 1 + s + s ^ { 2 } + s ^ { 3 } ) + \eta \right ]. \quad \, ( 2 4 ) \\ \text{Multiplying} \, ( 2 4 ) \, \text{with} \, ( - 1 + s ^ { 2 } + 2 s ^ { 3 } ) ( 1 + s + s ^ { 2 } + s ^ { 3 } ) ( 1 - 3 s ^ { 2 } - 8 s ^ { 3 } + 2 b ^ { 2 } + 6 b ^ { 2 } s ) ^ { 2 } \alpha ^ { 1 4 } \\ \text{ implies that}$$

$$\text{mases} \text{max} \\ M _ { 1 } + M _ { 2 } \alpha ^ { 2 } + M _ { 3 } \alpha ^ { 4 } + M _ { 4 } \alpha ^ { 6 } + M _ { 5 } \alpha ^ { 8 } + M _ { 6 } \alpha ^ { 1 0 } + M _ { 7 } \alpha ^ { 1 2 } + M _ { 8 } \alpha ^ { 1 4 } \\ + \alpha \left [ M _ { 9 } + M _ { 1 0 } \alpha ^ { 2 } + M _ { 1 1 } \alpha ^ { 4 } + M _ { 1 2 } \alpha ^ { 6 } + M _ { 1 3 } \alpha ^ { 8 } + M _ { 1 4 } \alpha ^ { 1 0 } \\ + M _ { 1 5 } \alpha ^ { 1 2 } + M _ { 1 6 } \alpha ^ { 1 4 } \right ] = 0, \quad ( 2 5 ) \\ 8$$

[ ] Multiplying (24) with ( -1+ s 2 +2 s 3 )(1+ s + s 2 + s 3 )(1 -3 s 2 -8 s 3 +2 b 2 +6 b 2 s ) 2 α 14 implies that (25)

## where

- M 1 := -128( n +1) cβ 15 , M 2 := 2 ( [ n +1) ( [ -385 + 96 b 2 ) cβ 2 -64 ηβ ] +128 ( λ r 0 + s 0 ) β +48 nr 00 ] β 11 , M 3 := -[ ( n +1)[4( -283 b 2 +243 + 18 b 4 ) cβ 2 -6(32 b 2 -59) ηβ ] + [12( -59 + 32 b 2 ) λ r ( 0 + s 0 ) -96((3 n -1) s 0 -r 0 ] β + 3( -24 b 2 +36 -219 n +72 nb 2 ) r 00 ] β , 9 M 4 := [ ( n +1) [ -2(29 -738 b 2 +208 b 4 ) cβ 2 -3( -172 b 2 +21 + 24 b 4 ) ηβ ] + ( -159 nb 2 -132 -39 n +96 b 2 ) r 00 -3( -48 b 2 +123 + 72 nb 2 -277 n s β ) 0 + 3(24 b 2 +86) r β 0 +6 ( λ -172 b 2 +21+24 b 4 )( s 0 + r 0 ) β β , ] 7 M 5 := [ ( n +1)[ -8( -27 b 2 +70 b 4 -41) cβ 2 -4(47 b 4 -40 -32 b 2 ) ηβ ] + (15 nb 2 +20 -55 n +108 b 2 ) r 00 +8 (47 λ b 4 -40 -32 b 2 )( r 0 + s 0 ) β -2 ( [ -262 b 2 +278 + 303 nb 2 -147 n s ) 0 -(94 b 2 +32) r 0 ] β β ] 5 M 6 := 2 ( [ n +1) [ -2(4 b +1)(4 b -1)(4 b 2 +13) cβ 2 -10(1 + 20 b 2 +6 b 4 ) ηβ ] + (11 n -40 b 2 +35 nb 2 +20) r 00 +20 (1 + 20 λ b 2 +6 b 4 )( r 0 + s 0 ) β -2(32 n +51 + 129 nb 2 -294 b 2 ) s β 0 -(30 b 2 -50) r β 0 ] β , 3 M 7 := -[ ( n +1) [ -4( -17 b 2 -7 + 30 b 4 ) cβ 2 -6( -1 + 10 b 4 ) β ] +(3 n +12) b 2 r 00 -12 λ (1 -10 b 4 )( s 0 + r 0 ) -6 ( [ nb 2 -n -2 + 14 b 2 ) s 0 -10 b 2 r 0 ] β β, ] M 8 := 4 ( [ n +1) 2(1 + 2 [ b 2 )(8 b 2 +1) cβ +(1 + 2 b 2 ) 2 η ] -2 λ (1 + 2 b 2 ) 2 ( s 0 + r 0 ) + [ -57 nb 2 -64( n +1) b 4 -8 n -55 b 2 +6 ] r 00 -(2 -4 b 2 ) r 0 + [ n +(4 + 2 n b ) 2 -1 ] s 0 ] , M 9 := -416( n +1) cβ 14 , M 10 := [ ( n +1)[( -1037 + 616 b 2 ) cβ 2 -288 ηβ ] + 576 λ r ( 0 + s 0 ) β +(204 n -6) r 00 ] β 12 , M 11 := -1 2 [ ( n +1)[8(57 b 4 -385 b 2 +143) cβ 2 -2(424 b 2 -267) ηβ ] + 4 (424 [ λ b 2 -267)( r 0 + s 0 ) -4( -115 + 330 n s ) 0 +1320 r 0 ] β + (300 nb 2 +249 -189 n -120 b 2 ) r 00 ] β , 8 M 12 := 4 ( [ n +1)[ -(572 b 4 -932 b 2 -275) cβ 2 -4(39 b 4 -28 -102 b 2 ) ηβ ] -75 nb 2 -62 -89 n +144 b 2 r 00 +8 (39 λ b 4 -28 -102 b 2 )( r 0 + s 0 ) β -6[( -58 b 2 +100 + 81 nb 2 -109 n s ) 0 -(26 b 2 +34) r 0 ] β β , ] 6

$$M _ { 1 3 } \coloneqq \ \left [ ( n + 1 ) [ - 8 ( - 2 4 + 3 5 b ^ { 2 } + 4 7 b ^ { 4 } ) c \beta ^ { 2 } - 6 ( 2 6 b ^ { 4 } - 1 1 + 2 0 b ^ { 2 } ) \eta \beta \right ] \\ & + ( 5 1 n b ^ { 2 } + 3 3 - 6 n + 2 4 b ^ { 2 } ) r _ { 0 0 } + 1 2 \lambda ( 2 6 b ^ { 4 } - 1 1 + 2 0 b ^ { 2 } ) ( s _ { 0 } + r _ { 0 } ) \\ & - 6 ( - 1 1 8 b ^ { 2 } + 5 4 + 8 3 n b ^ { 2 } - 3 n ) s _ { 0 } \beta + 6 ( 2 6 b ^ { 2 } - 1 0 ) r _ { 0 } \beta \right ] \beta ^ { 4 }, \\ M _ { 1 4 } \coloneqq \ \left [ ( n + 1 ) [ - ( 5 6 b ^ { 4 } - 2 7 2 b ^ { 2 } - 3 9 ) c \beta ^ { 2 } - 4 ( 7 ( n + 1 ) b ^ { 4 } - 6 ( 1 + n ) - 2 2 n b ^ { 2 } ) \eta \beta \right ] \\ & + ( - 7 n b ^ { 2 } - 8 - 5 n + 3 2 b ^ { 2 } ) r _ { 0 0 } + 8 \lambda ( 7 b ^ { 4 } - 6 - 2 2 b ^ { 2 } ) ( r _ { 0 } + s _ { 0 } ) \beta \\ & + 2 ( - 1 5 4 b ^ { 2 } + 1 2 + 3 3 n b ^ { 2 } + 1 9 n ) s _ { 0 } \beta + 2 ( 1 4 b ^ { 2 } - 2 2 ) s _ { 0 } \beta \right ] \beta ^ { 2 } \\ M _ { 1 5 } \coloneqq \ \left [ ( n + 1 ) [ 4 ( 2 3 b ^ { 4 } + 5 b ^ { 2 } - 1 ) c \beta ^ { 2 } - ( 1 4 b ^ { 2 } + 1 ) ( 2 b ^ { 2 } + 1 ) \eta \beta \right ] \\ & - \frac { n + 1 } { 2 } ( 8 b ^ { 2 } + 1 ) r _ { 0 0 } - 2 \lambda ( 1 4 b ^ { 2 } + 1 ) ( 2 b ^ { 2 } + 1 ) ( s _ { 0 } + r _ { 0 } ) \beta \\ & - 2 ( - 6 b ^ { 2 } + 3 - 5 n b ^ { 2 } ) s _ { 0 } \beta - 2 ( 4 + 1 4 b ^ { 2 } ) r _ { 0 } \beta \right ], \\ M _ { 1 6 } \coloneqq \ ( n + 1 ) ( 1 + 2 b ^ { 2 } ) ^ { 2 } c \\ The term of ( 2 5 ) which is seemingly does not contain \alpha ^ { 2 } \, is \, M _ { 1 }. \, Since \, \beta ^ { 1 5 } \, is \, not \\ divisible by \alpha ^ { 2 }, \, then \, c = 0 \, \text{which implies that}$$

The term of (25) which is seemingly does not contain α 2 is M 1 . Since β 15 is not divisible by α 2 , then c = 0 which implies that

$$M _ { 1 } = M _ { 9 } = 0.$$

Therefore (25) reduces to following

$$M _ { 2 } + M _ { 3 } \alpha ^ { 2 } + M _ { 4 } \alpha ^ { 4 } + M _ { 5 } \alpha ^ { 6 } + M _ { 6 } \alpha ^ { 8 } + M _ { 7 } \alpha ^ { 1 0 } + M _ { 8 } \alpha ^ { 1 2 } = 0, \text{ \quad \ } ( 2 6 )$$

$$M _ { 1 0 } + M _ { 1 1 } \alpha ^ { 2 } + M _ { 1 2 } \alpha ^ { 4 } + M _ { 1 3 } \alpha ^ { 6 } + M _ { 1 4 } \alpha ^ { 8 } + M _ { 1 5 } \alpha ^ { 1 0 } + M _ { 1 6 } \alpha ^ { 1 2 } = 0. \quad ( 2 7 )$$

By plugging c = 0 in M 2 and M 10 , the only equations that don't contain α 2 are the following

$$8 \left [ 8 ( 2 \lambda ( r _ { 0 } + s _ { 0 } ) - ( n + 1 ) \eta ) + 6 n r _ { 0 0 } \right ] & = \tau _ { 1 } \alpha ^ { 2 }, \quad \quad ( 2 8 ) \\ 6 \left [ 4 8 ( 2 \lambda ( r _ { 0 } + s _ { 0 } ) - ( n + 1 ) \eta ) + ( 3 4 n - 1 ) r _ { 0 0 } \right ] & = \tau _ { 2 } \alpha ^ { 2 }, \quad \quad ( 2 9 )$$

where τ 1 = τ 1 ( x ) and τ 2 = τ 2 ( x ) are scalar functions on M . By eliminating [2 λ r ( 0 + s 0 ) -( n +1) ] from (28) and (29), we get η

$$\check { 6 \left [ 4 8 ( 2 \lambda ( r _ { 0 } + s _ { 0 } ) - ( n + 1 ) \eta ) + ( 3 4 n - 1 ) r _ { 0 0 } \check { \right ] } = \tau _ { 2 } \alpha ^ { 2 }, \quad \ ( 2 9 ) \\ \intertext { here } \tau _ { 1 } = \tau _ { 1 } ( x ) \text{ and } \tau _ { 2 } = \tau _ { 2 } ( x ) \text{ are scalar functions on } M. \text{ By eliminating}$$

$$r _ { 0 0 } = \tau \alpha ^ { 2 },$$

where τ = τ 2 -τ 1 -(18 n +1) . By (28) or (29), it follows that

$$2 \lambda ( r _ { 0 } + s _ { 0 } ) - ( n + 1 ) \eta = 0.$$

By (30), we have r 0 = τβ . Putting (30) and (31) in M 10 and M 11 yield

$$M _ { 1 0 } = & ( 2 0 4 n - 6 ) \tau \alpha ^ { 2 } \beta ^ { 1 2 }, & & ( 3 2 ) \\ & r & & ( 3 0 0 n - 1 0 0 \lambda ^ { 2 } \pm 2 0 n - 1 8 0 n } \quad. \,.$$

$$\stackrel { \cdots \nu } { \cdots } \stackrel { \cdots \cdots } { \cdots } \stackrel { \cdots \cdots } { \cdots } \stackrel { \cdots \cdots } { \cdots } \stackrel { \cdots } { \cdots } \,, \\ M _ { 1 1 } = & \left [ [ ( 6 6 0 n - 2 3 0 ) s _ { 0 } - 6 6 0 r _ { 0 } ] \beta - \frac { ( 3 0 0 n - 1 2 0 ) b ^ { 2 } + 2 4 9 - 1 8 9 n } { 2 } r _ { 0 0 } \tau \alpha ^ { 2 } \right ] \beta ^ { 2 } _ { 0 3 } )$$

By putting (32) and (33) into (27), we have

$$& [ ( 6 6 0 n - 2 3 0 ) s _ { 0 } - 6 6 0 r _ { 0 } ] \beta ^ { 1 0 } - \frac { 3 0 0 n b ^ { 2 } + 2 4 9 - 1 8 9 n - 1 2 0 b ^ { 2 } } { 2 } r _ { 0 0 } \tau \alpha ^ { 2 } \beta ^ { 9 } \\ + & \, ( 2 0 4 n - 6 ) \tau \beta ^ { 1 2 } - M _ { 1 2 } \alpha ^ { 2 } + M _ { 1 3 } \alpha ^ { 4 } + M _ { 1 4 } \alpha ^ { 6 } + M _ { 1 5 } \alpha ^ { 8 } + M _ { 1 6 } \alpha ^ { 1 0 } = 0. \ ( 3 4 )$$

$$n - 6 ) \tau \beta ^ { 1 2 } - M$$

The only equations of (34) that do not contain α 2 is [(204 n -6) τβ 2 +(660 n -230) s 0 -660 r 0 ] β 10 . Since β 10 is not divisible by α 2 , then we have

$$[ ( 2 0 4 n - 6 ) \tau \beta ^ { 2 } + ( 6 6 0 n - 2 3 0 ) s _ { 0 } - 6 6 0 r _ { 0 } ] = 0. \quad \quad ( 3 5 )$$

By Lemma 3.1, we always have s j = 0. Then (35), reduces to following

$$( 2 0 4 n - 6 ) \tau \beta ^ { 2 } - 6 6 0 r _ { 0 } = 0.$$

Thus

$$2 ( 2 0 4 n - 6 ) \tau b _ { i } \beta - 6 6 0 \tau b _ { i } = 0. \quad \quad \quad ( 3 7 )$$

By multiplying (37) with b i , we have

$$\tau = 0.$$

Thus by (31), we get η = 0 and then S = ( n +1) cF . By (30), we get r ij = 0. Therefore Lemma 3.1, implies that S = 0. This completes the proof.

Proof of Theorem 1.1: Let F be an isotropic Berwald metric (3) with almost isotropic flag curvature (1). In [20], it is proved that every isotropic Berwald metric (3) has isotropic S-curvature (2).

Conversely, suppose that F is of isotropic S-curvature (2) with scalar flag curvature K . In [11], it is showed that every Finsler metric of isotropic Scurvature (2) has almost isotropic flag curvature (1). Now, we are going to prove that F is a isotropic Berwald metric. In [6], it is proved that F is an isotropic Berwald metric (3) if and only if it is a Douglas metric with isotropic mean Berwald curvature (5). On the other hand, every Finsler metric of isotropic S-curvature (2) has isotropic mean Berwald curvature (5). Thus for completing the proof, we must show that F is a Douglas metric. By Proposition 3.2, we have S = 0. Therefore by Theorem 1.1 in [11], F must be of isotropic flag curvature K = σ x ( ). By Proposition 3.2, β is a Killing 1-form with constant length with respect to α , that is, r ij = s j = 0. Then (14), (15) and (16) reduce to

$$G ^ { i } - \bar { G } ^ { i } = \alpha Q s ^ { i } _ { \ 0 }, \ \ J _ { i } = - \frac { \Phi s _ { i 0 } } { 2 \alpha \Delta }, \ \ \bar { J } = 0.$$

By (12), we get

$$\lambda I _ { i } b ^ { i } = \frac { - \Phi } { 2 \Delta F } ( \phi - s \phi ^ { \prime } ) ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ).$$

We consider two case:

Case 1. Let dimM ≥ 3. In this case, by Schur Lemma F has constant flag curvature and (21) holds. Thus by (38) and (39), the equation (21) reduces to following

$$\frac { \Phi s _ { i 0 } } { 2 \alpha \Delta } a ^ { i k } s _ { k 0 } + \frac { \Phi s _ { l 0 } } { 2 \alpha \Delta } \Big ( \alpha Q s ^ { l } _ { 0 } \Big ) _ {. i } b ^ { i } - K F \frac { \Phi } { 2 \Delta } ( \phi - s \phi ^ { \prime } ) ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ) = 0. \quad ( 4 0 ) \\ \text{Bv assumption } \Phi \neq 0. \text{ Thus } b v \ ( 4 0 ). \text{ we get}$$

By assumption Φ = 0. Thus by (40), we get

/negationslash

$$s _ { i 0 } s _ { 0 } ^ { i } + s _ { l 0 } \left ( \alpha Q s _ { 0 } ^ { l } \right ) _ {. i } b ^ { i } - K F \alpha ( \phi - s \phi ^ { \prime } ) ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ) = 0. \quad \ ( 4 1 ) \\ \text{The following holds}$$

The following holds

$$\left ( \alpha Q s ^ { l } _ { \, 0 } \right ) _ {. i } b ^ { i } = s Q s ^ { i } _ { \, 0 } + Q ^ { \prime } s ^ { i } _ { \, 0 } ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ). \\ \text{n be rewritten as follows}$$

Then (41) can be rewritten as follows

$$s _ { i 0 } s ^ { i } _ { 0 } \Delta - K \alpha ^ { 2 } \phi ( \phi - s \phi ^ { \prime } ) ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ) = 0.$$

By (11), (23) and (42), we obtain

$$\begin{array} { l l l l } \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \\ & \left [ 1 - \frac { s ( 1 + 2 s + 3 s ^ { 2 } ) } { ( - 1 + s ^ { 2 } + 2 s ^ { 3 } ) } + \frac { 2 ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ) ( 1 + 3 s ) ( 1 + s + s ^ { 2 } + s ^ { 3 } ) } { ( - 1 + s ^ { 2 } + 2 s ^ { 3 } ) ^ { 2 } } \right ] s _ { i 0 } s ^ { i } _ { 0 } \\ & - K ( 1 + s + s ^ { 2 } + s ^ { 3 } ) \alpha ^ { 2 } \left [ 1 + s + s ^ { 2 } + s ^ { 3 } - s ( 1 + 2 s + 3 s ^ { 2 } ) \right ] ( b ^ { 2 } - s ^ { 2 } ) = 0 ( 4 3 ) \\ & \text{Multiplying (43) with (-1 + s ^ { 2 } + 2 s ^ { 3 } ) ^ { 2 } \alpha ^ { 1 2 } \text{ yields} \end{array}$$

Multiplying (43) with ( -1 + s 2 +2 s 3 ) 2 α 12 yields

$$A + \alpha B = 0,$$

where

$$\text{where} \quad \\ A & = - K b ^ { 2 } \alpha ^ { 1 4 } + ( 2 b ^ { 2 } + 1 ) ( K \beta ^ { 2 } + s _ { i 0 } s ^ { i } _ { 0 } ) \alpha ^ { 1 2 } \\ & + 2 ( 3 K b ^ { 2 } \beta ^ { 2 } + 4 s _ { i 0 } s ^ { i } _ { 0 } b ^ { 2 } - K \beta ^ { 2 } - s _ { i 0 } s ^ { i } _ { 0 } ) \beta ^ { 2 } \alpha ^ { 1 0 } \\ & - ( 6 K \beta ^ { 2 } + 1 1 s _ { i 0 } s ^ { i } _ { 0 } + 2 0 K \beta ^ { 2 } b ^ { 2 } - 6 s _ { i 0 } s ^ { i } _ { 0 } ) \beta ^ { 4 } \alpha ^ { 8 } \\ & - ( - 2 0 K \beta ^ { 2 } + 5 K \beta ^ { 2 } b ^ { 2 } + 8 s _ { i 0 } s ^ { i } _ { 0 } ) \beta ^ { 6 } \alpha ^ { 6 } + ( K \beta ^ { 1 0 } ) ( 2 6 b ^ { 2 } + 5 ) \alpha ^ { 4 } \\ & - 2 K \beta ^ { 1 2 } ( 1 3 - 4 b ^ { 2 } ) \alpha ^ { 2 } - 8 K \beta ^ { 1 4 }, & ( 4 4 ) \\ B & = - ( K b ^ { 2 } \beta ) \alpha ^ { 1 2 } + ( 1 + 8 b ^ { 2 } ) ( K b ^ { 2 } \beta ^ { 2 } + s _ { i 0 } s ^ { i } _ { 0 } ) \beta \alpha ^ { 1 0 } \\ & - 2 ( 3 K b ^ { 2 } \beta ^ { 2 } - 4 s _ { i 0 } s ^ { i } _ { 0 } b ^ { 2 } + 4 K \beta ^ { 2 } + 5 s _ { i 0 } s ^ { i } _ { 0 } ) \beta ^ { 3 } \alpha ^ { 8 } \\ & + ( 6 K \beta ^ { 2 } - 1 1 s _ { i 0 } s ^ { i } _ { 0 } - 2 0 K \beta ^ { 2 } b ^ { 2 } ) \beta ^ { 5 } \alpha ^ { 6 } \\ & + ( 5 K \beta ^ { 9 } ) ( 3 b ^ { 2 } + 4 ) \alpha ^ { 4 } + ( 5 K \beta ^ { 1 1 } ) ( - 3 + 4 b ^ { 2 } ) \alpha ^ { 2 } - 2 0 \alpha K \beta ^ { 1 3 }. \\ \text{ Obviously, we have } A = 0 \text{ and } B = 0. \text{ } B \text{ } A = 0 \text{ and the fact that } \beta ^ { 1 4 } \text{ is not divisible by } \alpha ^ { 2 }, \text{ we get } K = 0.$$

Obviously, we have A = 0 and B = 0.

By A = 0 and the fact that β 14 is not divisible by α 2 , we get K = 0. Therefore (43) reduces to following

$$s _ { i 0 } s _ { \, 0 } ^ { i } = a _ { i j } s _ { \, 0 } ^ { j } s _ { \, 0 } ^ { i } = 0.$$

Because of positive-definiteness of the Riemannian metric α , we have s i 0 = 0, i.e., β is closed. By r 00 = 0 and s 0 = 0, it follows that β is parallel with respect to α . Then F = α + β + β 2 α + β 3 α 2 is a Berwald metric. Hence F must be locally Minkowskian.

Case 2. Let dim M = 2. Suppose that F has isotropic Berwald curvature (3). In [20], it is proved that every isotropic Berwald metric (3) has isotropic Scurvature, S = ( n +1) cF . By Proposition 3.2, c = 0. Then by (3), F reduces to a Berwald metric. Since F is non-Riemannian, then by Szab´'s rigidity Theorem o for Berwald surface (see [2] page 278), F must be locally Minkowskian.

Acknowledgment. The authors would like to thank the referee's valuable suggestions.

## References

- [1] S. B´cs´ and M. Matsumoto, a o On Finsler spaces of Douglas type, A generalization of notion of Berwald space , Publ. Math. Debrecen. 51 (1997), 385-406.

- [2] D. Bao, S. S. Chern and Z. Shen, An Introduction to Riemann-Finsler Geometry , Springer-Verlag, 2000.

- [3] X. Chun-Huan and X. Cheng, On a class of weakly-Berwald ( α, β ) -metrics , J. Math. Res. Expos. 29 (2009), 227-236.

- [4] X. Cheng and Z. Shen, Randers metric with special curvature properties , Osaka. J. Math. 40 (2003), 87-101.

- [5] X. Cheng and Z. Shen, A class of Finsler metrics with isotropic Scurvature , Israel. J. Math. 169 (2009), 317-340.

- [6] X. Chen and Z. Shen, On Douglas metrics , Publ. Math. Debrecen. 66 (2005), 503-512.

- [7] X. Cheng, H. Wang and M. Wang, ( α, β ) -metrics with relatively isotropic mean Landsberg curvature , Publ. Math. Debrecen. 72 (2008), 475-485.

- [8] N. Cui, On the S-curvature of some ( α, β ) -metrics , Acta. Math. Scientia, Series: A. 26 (7) (2006), 1047-1056.

- [9] I.Y. Lee and M.H. Lee, On weakly-Berwald spaces of special ( α, β ) -metrics , Bull. Korean Math. Soc. 43 (2) (2006), 425-441.

- [10] M. Matsumoto, Theory of Finsler spaces with ( α, β ) -metric , Rep. Math. Phys. 31 (1992), 43-84.

- [11] B. Najafi, Z. Shen and A. Tayebi , Finsler metrics of scalar flag curvature with special non-Riemannian curvature properties , Geom. Dedicata. 131 (2008), 87-97.

- [12] H. S. Park and E. S. Choi, On a Finsler spaces with a special ( α, β ) -metric , Tensor, N. S. 56 (1995), 142-148.

- [13] H. S. Park and E. S. Choi, Finsler spaces with an approximate Matsumoto metric of Douglas type , Comm. Korean. Math. Soc. 14 (1999), 535-544.

- [14] H. S. Park and E. S. Choi, Finsler spaces with the second approximate Matsumoto metric , Bull. Korean. Math. Soc. 39 (1) (2002), 153-163.

- [15] H. S. Park, I. Y. Lee and C. K. Park, Finsler space with the general approximate Matsumoto metric , Indian J. Pure. Appl. Math. 34 (1) (2002), 59-77.

- [16] H. S. Park, I.Y. Lee, H. Y. Park and B. D. Kim, Projectively flat Finsler space with an approximate Matsumoto metric , Comm. Korean. Math. Soc. 18 (2003), 501-513.

- [17] Z. Shen, Differential Geometry of Spray and Finsler Spaces , Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 2001.

- [18] A. Tayebi and B. Najafi, On isotropic Berwald metrics , Ann. Polon. Math. 103 (2012), 109-121.

- [19] A. Tayebi, E. Peyghan and H. Sadeghi, On Matsumoto-type Finsler metrics , Nonlinear Analysis: RWA. 13 (2012), 2556-2561.

- [20] A. Tayebi and M. Rafie Rad, S-curvature of isotropic Berwald metrics , Sci. China. Series A: Math. 51 (2008), 2198-2204.

Akbar Tayebi and Tayebeh Tabatabaeifar Faculty of Science, Department of Mathematics University of Qom Qom. Iran Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected]

Esmaeil Peyghan

Faculty of Science, Department of Mathematics Arak University 38156-8-8349 Arak. Iran

Email: [email protected] | null | [

"A. Tayebi",

"T. Tabatabaeifar",

"E. Peyghan"

] | 2014-07-31T08:55:09+00:00 | 2014-07-31T08:55:09+00:00 | [

"math.DG",

"53B40, 53C60, 53C25"

] | On the Second Approximate Matsumoto Metric | In this paper, we study the second approximate Matsumoto metric on a manifold

M. We prove that F is of scalar flag curvature and isotropic S-curvature if and

only if it is isotropic Berwald metric with almost isotropic flag curvature. |

1408.0239v1 | ## WIYN OPEN CLUSTER STUDY. LX. SPECTROSCOPIC BINARY ORBITS IN NGC 6819

Katelyn E. Milliman 1,6 , Robert D. Mathieu 1,6 , Aaron M. Geller 2,3 , Natalie M. Gosnell 1 , Søren Meibom 4 , and Imants Platais 5

Draft version August 4, 2014

## ABSTRACT

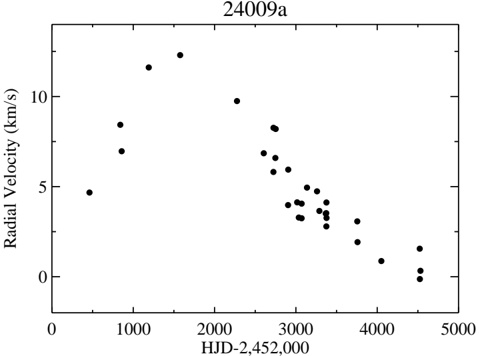

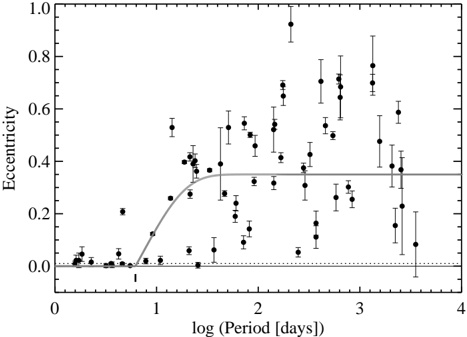

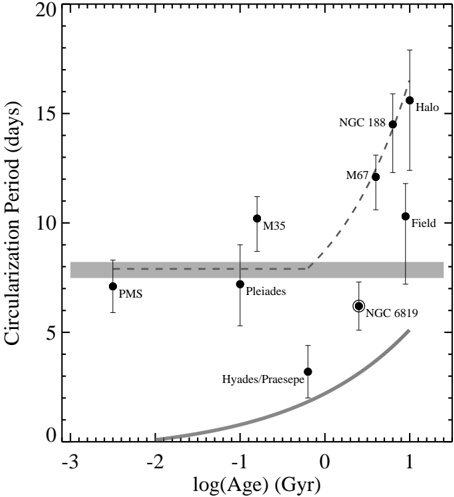

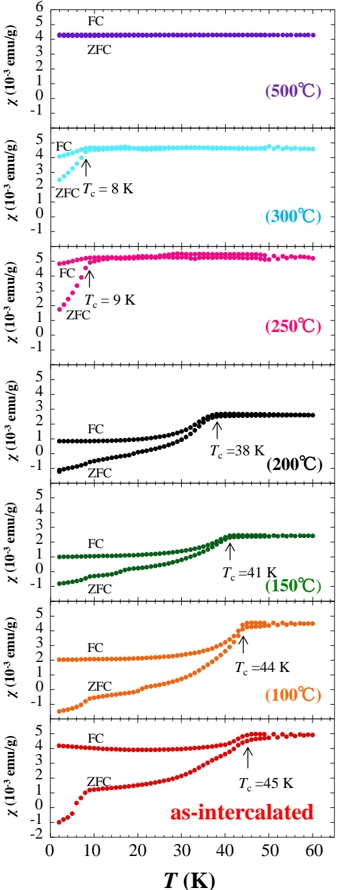

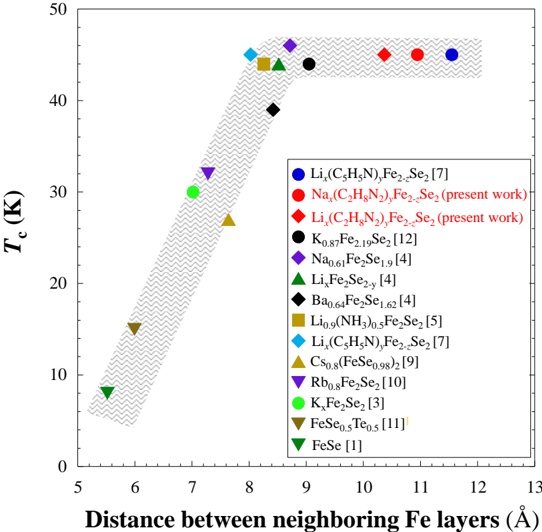

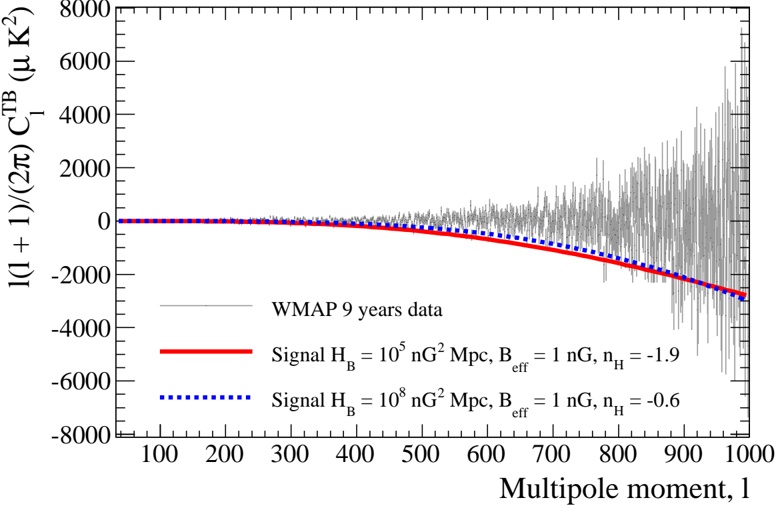

We present the current state of the WOCS radial-velocity (RV) survey for the rich open cluster NGC 6819 (2.5 Gyr) including 93 spectroscopic binary orbits with periods ranging from 1.5 to 8,000 days. These results are the product of our ongoing RV survey of NGC 6819 using the Hydra Multi-Object Spectrograph on the WIYN 3.5 m telescope. We also include a detailed analysis of multiple prior sets of optical photometry for NGC 6819. Within a 1 ◦ field of view, our stellar sample includes the giant branch, the red clump, and blue straggler candidates, and extends to almost 2 mag below the main-sequence (MS) turnoff. For each star observed in our survey we present all RV measurements, the average RV and velocity variability information. Additionally, we discuss notable binaries from our sample, including eclipsing binaries (WOCS 23009, WOCS 24009, and WOCS 40007), stars noted in Kepler asteroseismology studies (WOCS 4008, WOCS 7009, and WOCS 8007), and potential descendants of past blue stragglers (WOCS 1006 and WOCS 6002). We find the incompletenesscorrected binary fraction for all MS binaries with periods less than 10 4 days to be 22% ± 3% and a tidal circularization period of 6 2 . +1 1 . -1 1 . days for NGC 6819.

Subject headings:

## 1. INTRODUCTION

The rich intermediate-age open cluster NGC 6819 (2.5 Gyr; α = 19 41 h m 17 s . 5 (J2000), δ =+40 11 47 ; ◦ ′ ′′ l =74 ◦ . 0, b =+8 ◦ . 5) is one of four open clusters located within the field of view of the Kepler Mission and as such has experienced an increase in interest in recent years. Research on this cluster includes deep photometric studies (Rosvick & Vandenberg 1998, Kalirai et al. 2001, Yang et al. 2013), a time-series study (Street et al. 2002, Street et al. 2005), a moderately high-precision radial-velocity (RV) survey (Hole et al. 2009), studies of metal abundance (Bragaglia et al. 2001, Anthony-Twarog et al. 2013), and proper-motion measurements (Sanders 1972, Platais et al. 2013). Other research has studied the X-ray properties of NGC 6819 (Gosnell et al. 2012) resulting in the discovery of a dozen sources including a candidate quiescent low-mass Xray binary. Kepler data have enabled a number of asteroseismology studies of red giants in NGC 6819 that have investigated cluster membership (Stello et al. 2010, Stello et al. 2011), provided model-independent estimates of cluster parameters such as distance and

Electronic address: email: [email protected]

- 2 Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics (CIERA) and Department of Physics and Astronomy, Northwestern University, 2145 Sheridan Rd, Evanston, IL 60208, USA

- 1 Department of Astronomy, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 475 North Charter St, Madison, WI 53706, USA

- 3 Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Chicago, 5640 S. Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

- 5 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, 3400 North Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA

- 4 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA

6 Visiting Astronomer, Kitt Peak National Observatory, National Optical Astronomy Observatory, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under cooperative agreement with the National Science Foundation.

age (Basu et al. 2011), and integrated red giant branch (RGB) mass-loss (Miglio et al. 2012). Kepler data have also been used to detect eclipsing binaries in NGC 6819 that have yielded stellar mass, radius, and age measurements (Sandquist et al. 2013, Jeffries et al. 2013).

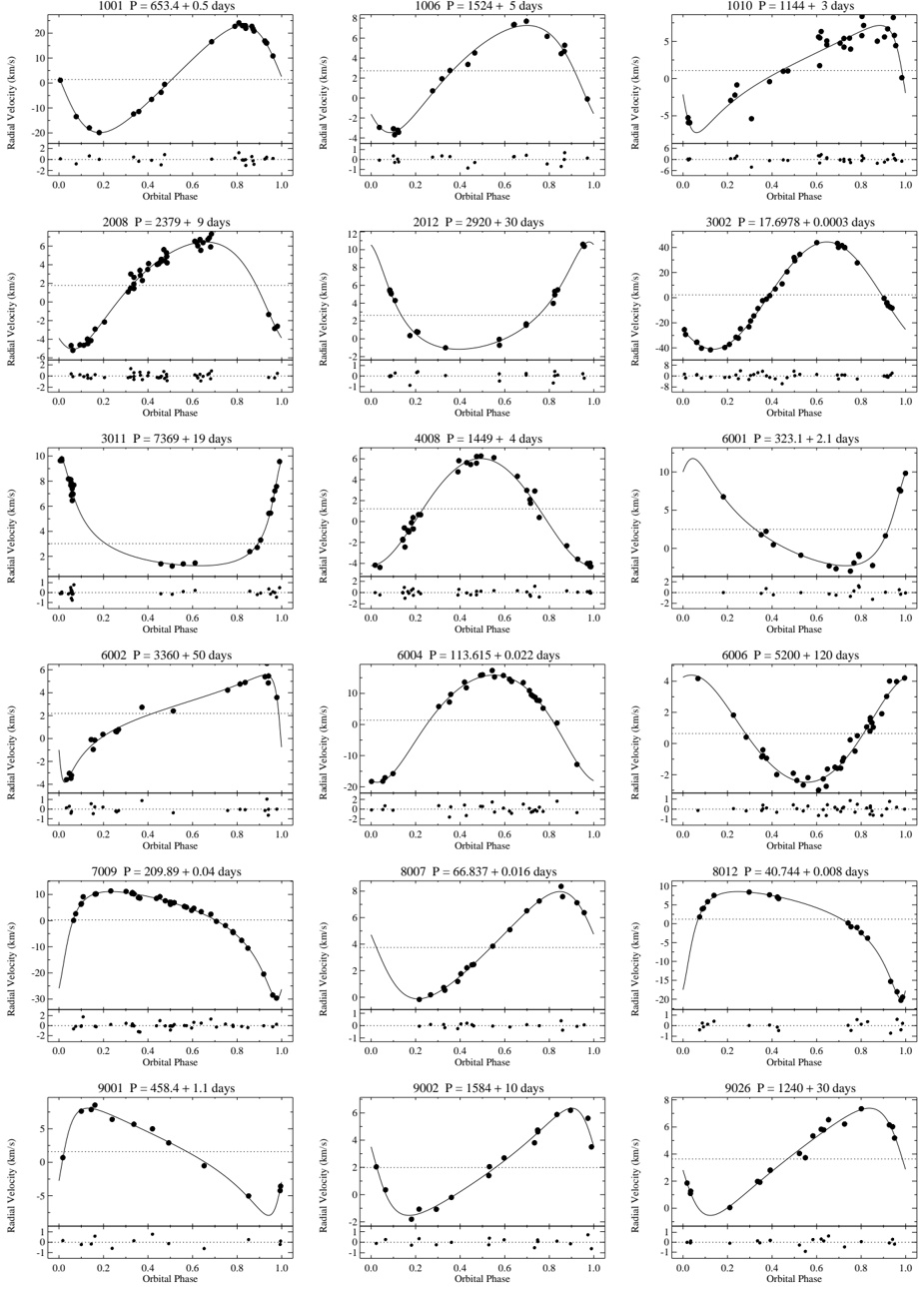

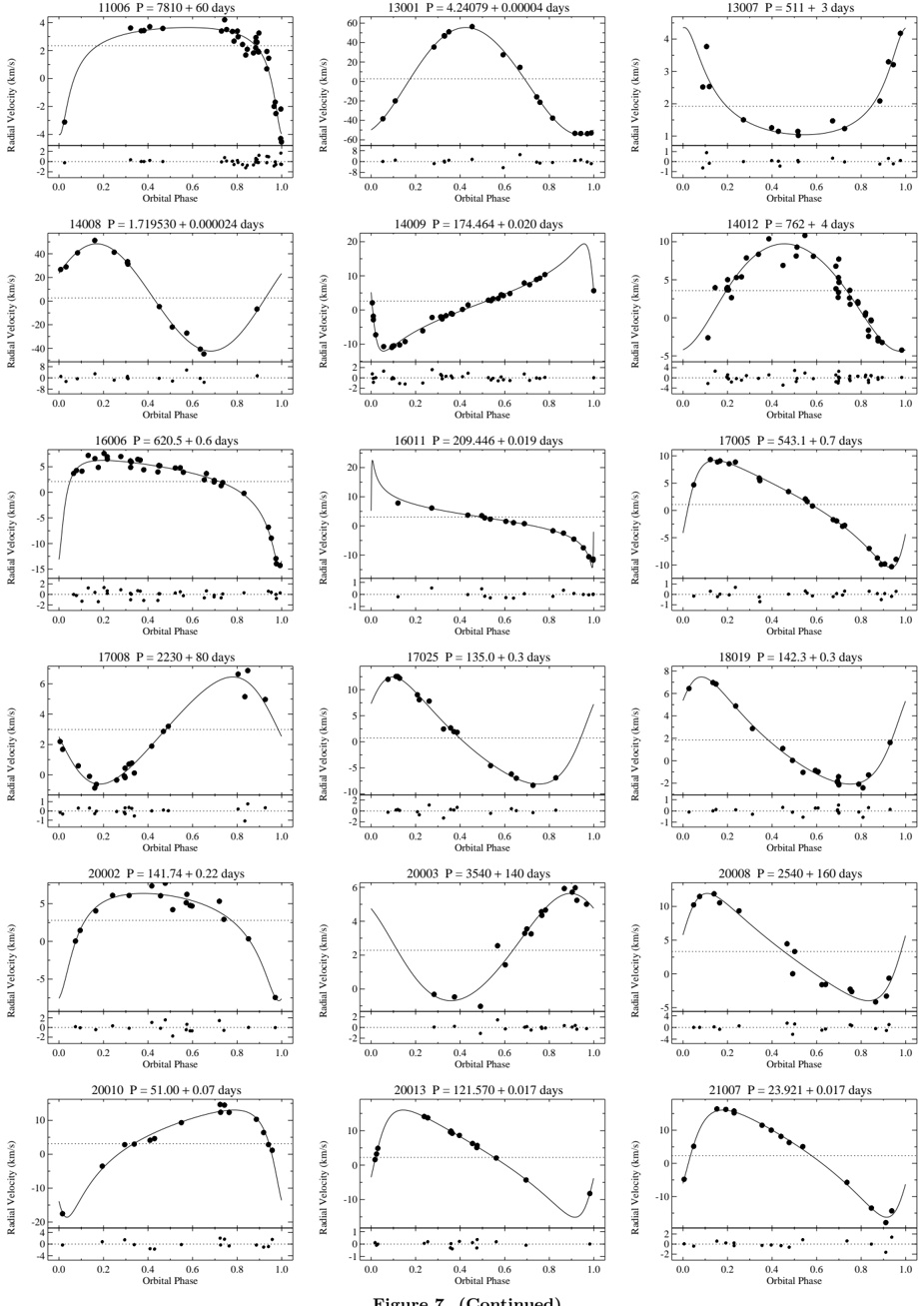

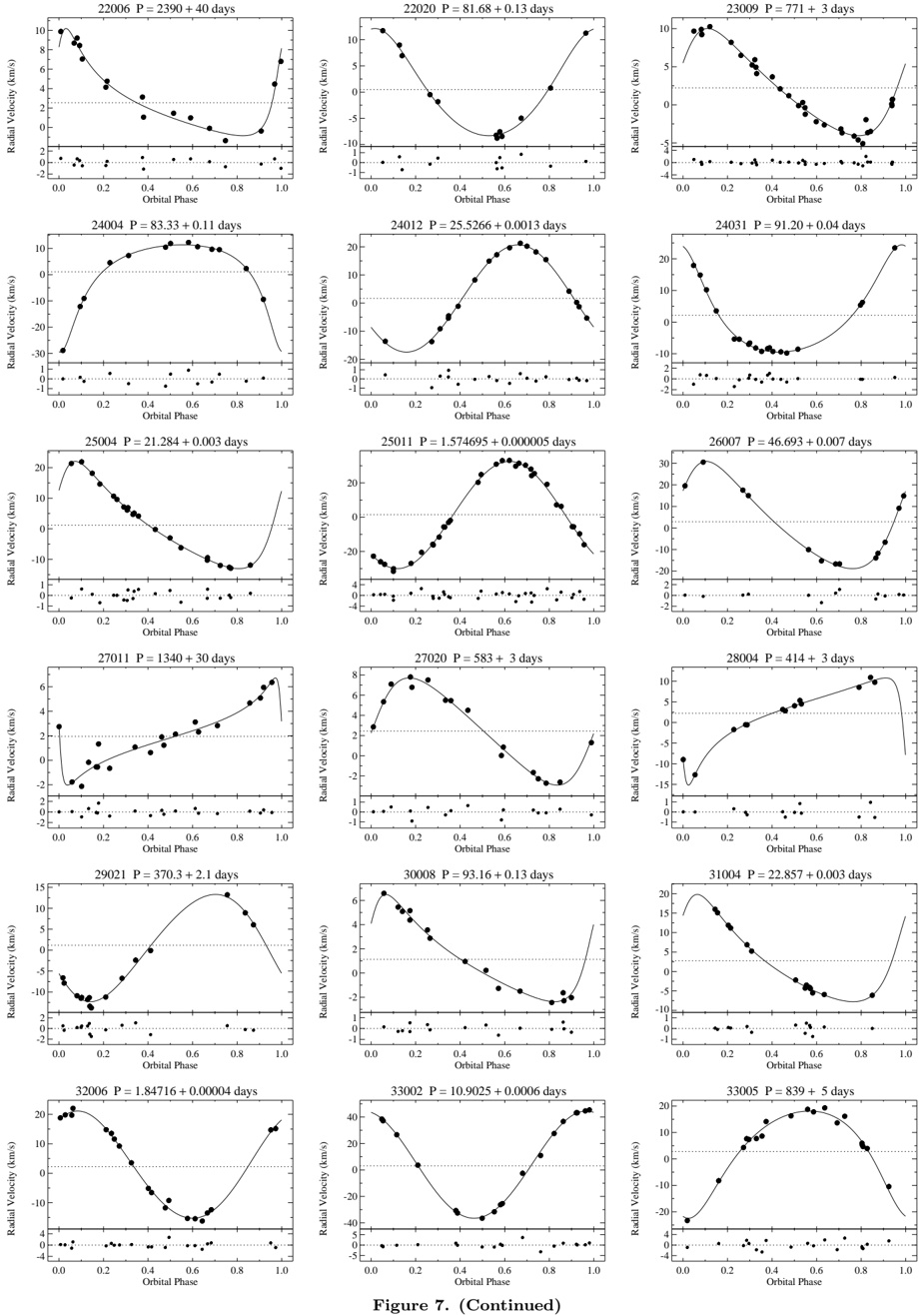

As part of the WIYN Open Cluster Study (WOCS; Mathieu 2000) we have continued the moderately highprecision RV survey of NGC 6819 discussed in Hole et al. (2009). Our ongoing RV survey covers a 1 ◦ diameter region on the sky and includes giant branch, red clump, upper main-sequence (MS), and blue straggler candidates. In this paper we present 93 spectroscopic binary orbits, as well as variability information for all stars observed as part of our RV survey. In Section 2, we discuss the photometry used in this study. Section 3 details the proper-motion membership information presented in Platais et al. (2013) that we have incorporated into our RV survey and analysis of NGC 6819. We describe the details and results of our RV survey in Section 4 including our observations, completeness, and RV membership probabilities. In Section 5, we provide 93 single-lined (SB1) and double-lined (SB2) orbital solutions for binary cluster members of NGC 6819. Binaries identified as interesting stars from XMM Newton -or Kepler observations and stars that are potential triple systems are discussed in Section 6. We analyze the circularization period (CP) of NGC 6819 in Section 7 and the binary frequency for stars with periods under 10 4 days in Section 8. Section 9 summarizes our current results for the WOCS RV survey of NGC 6819.

## 2. CLUSTER PHOTOMETRY

The first WOCS NGC 6819 RV paper, Hole et al. (2009), utilized four sources of CCD BV photometry: Rosvick & Vandenberg (1998), Kalirai et al. (2001), and two sets of WOCS photometry taken at the WIYN 0.9 m telescope in 1998 and 2003 (Sarrazine et al. 2003).

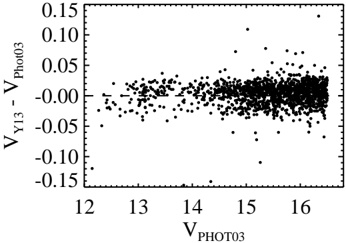

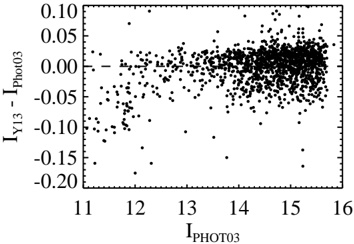

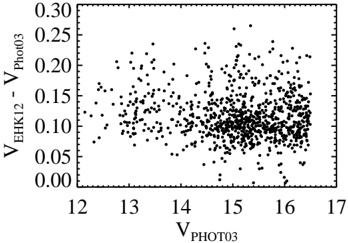

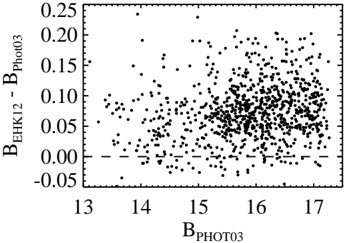

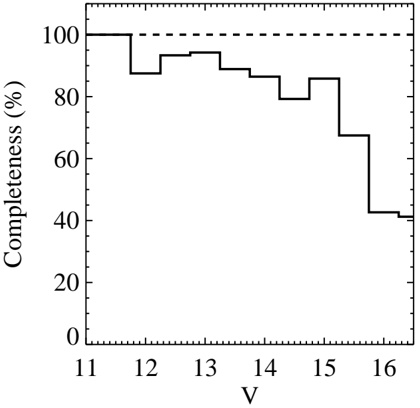

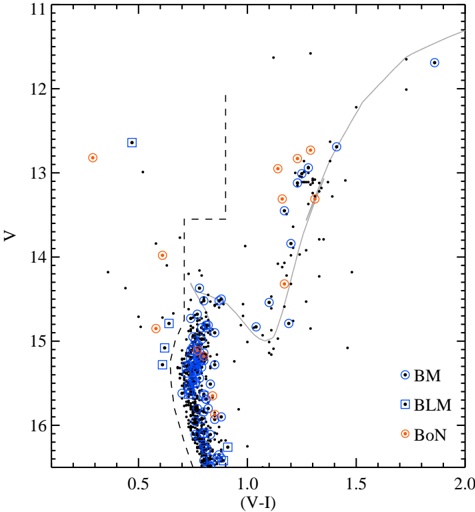

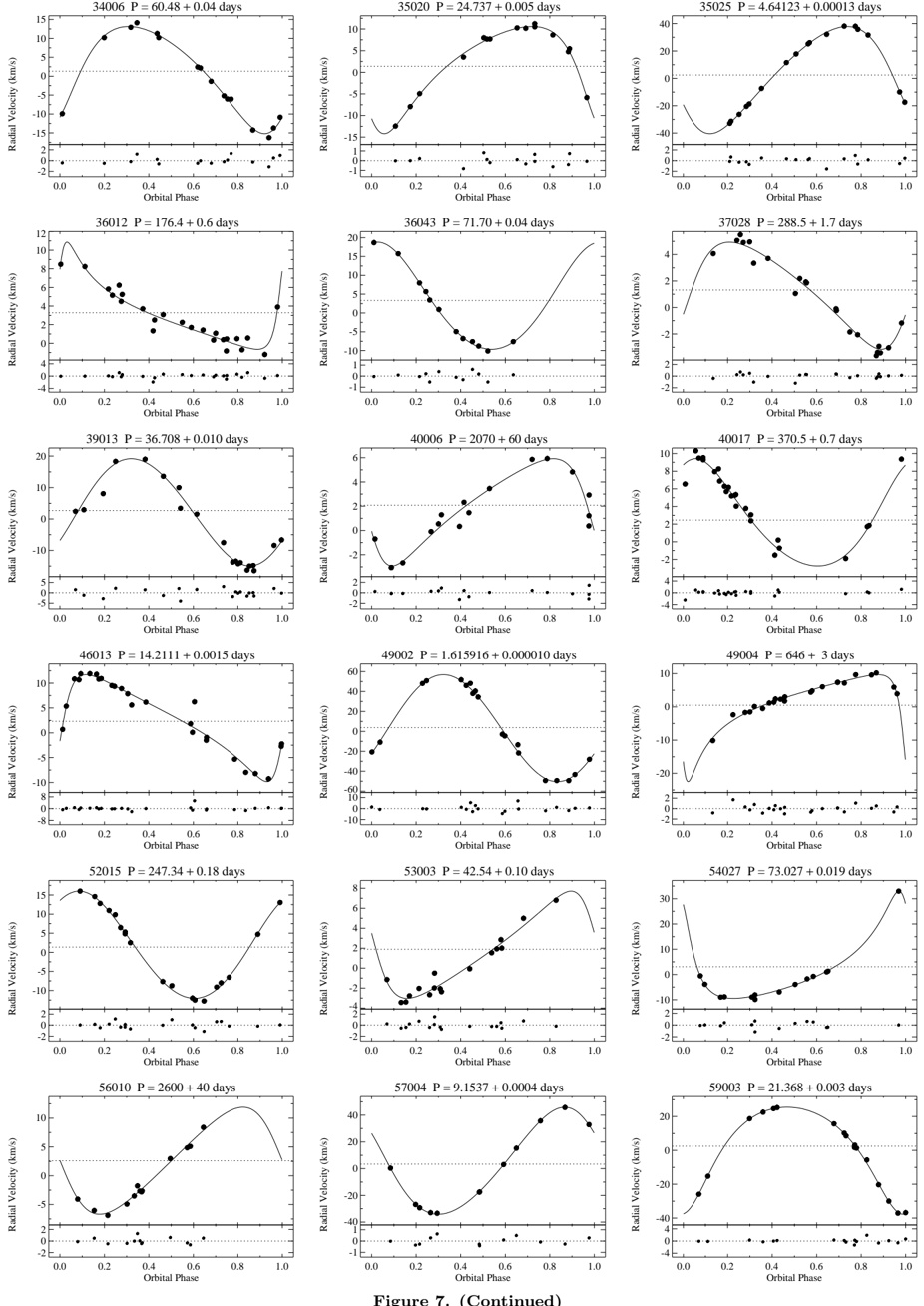

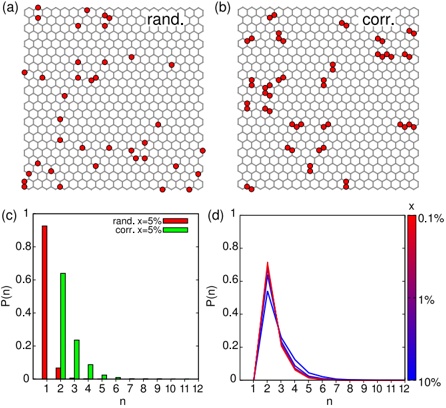

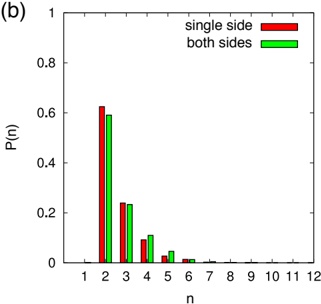

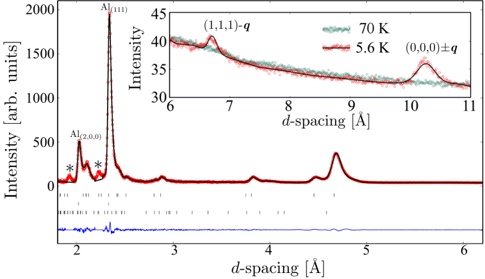

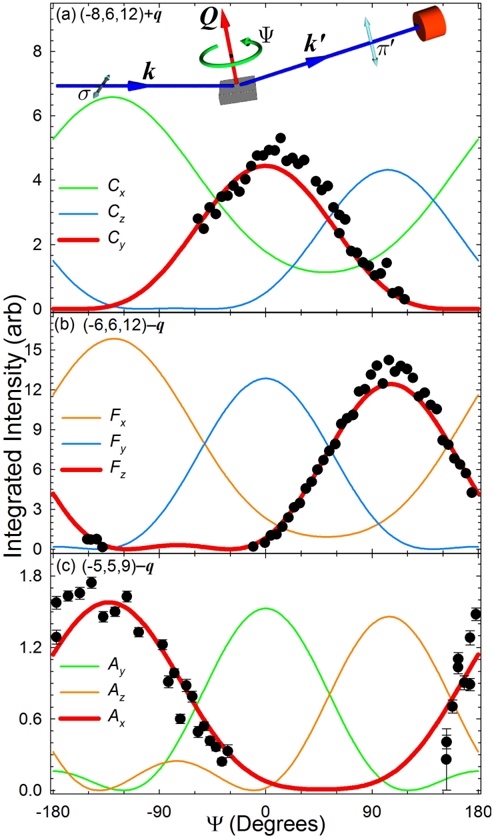

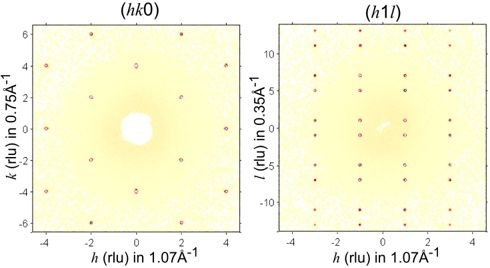

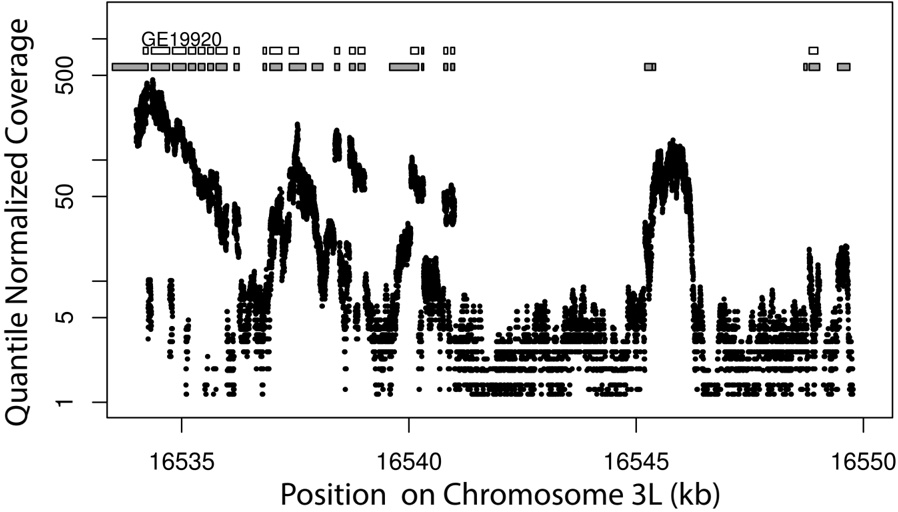

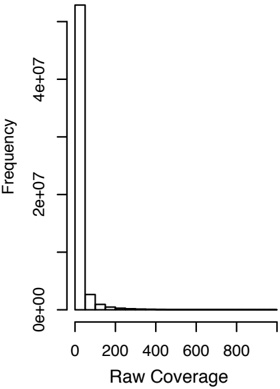

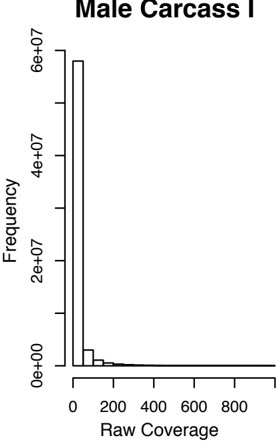

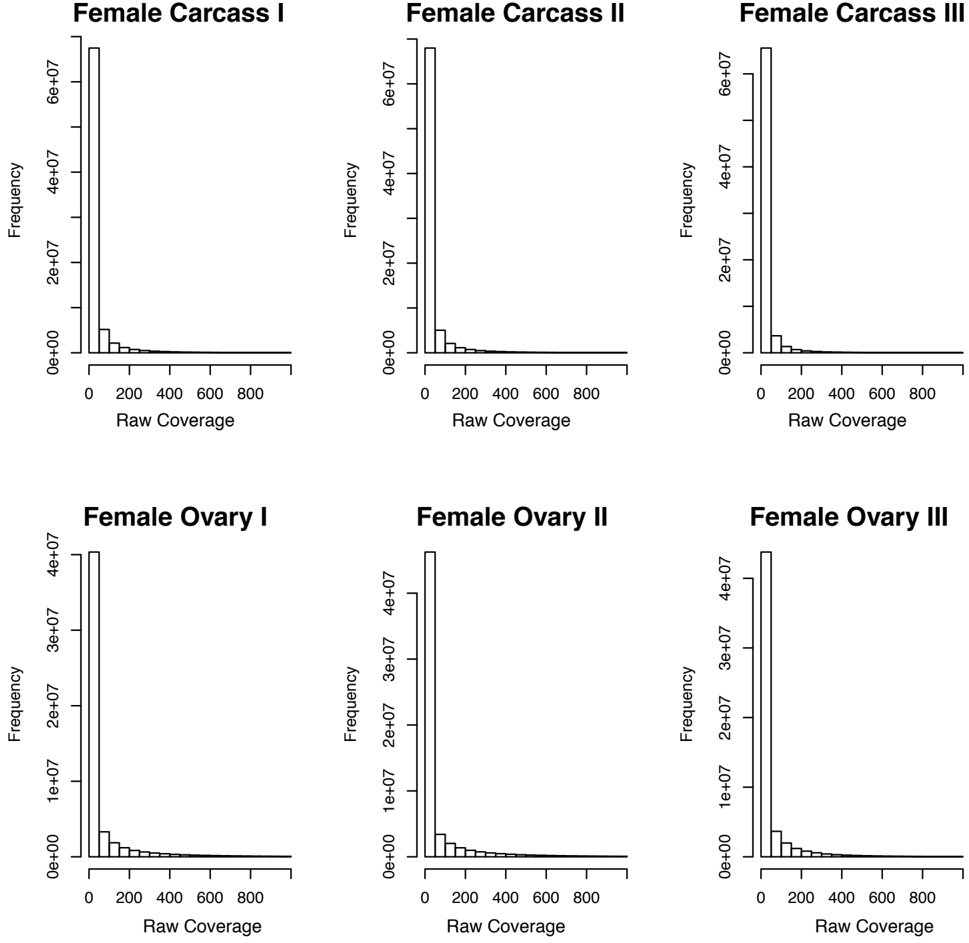

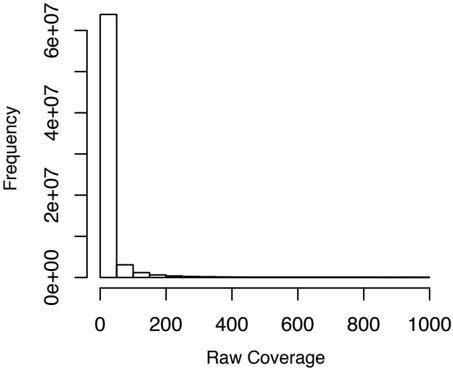

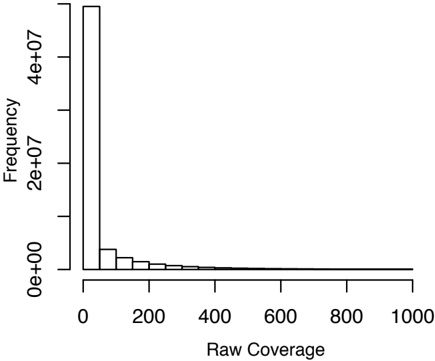

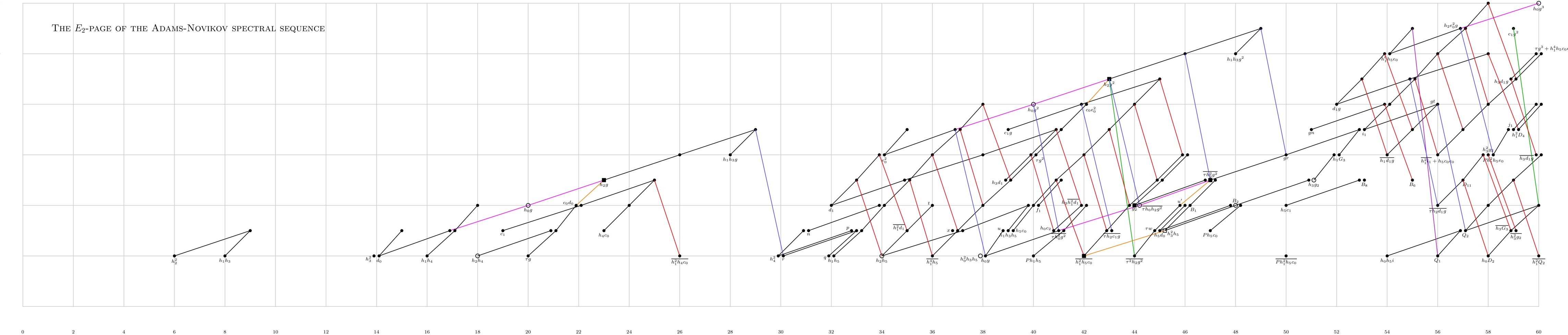

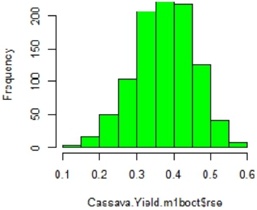

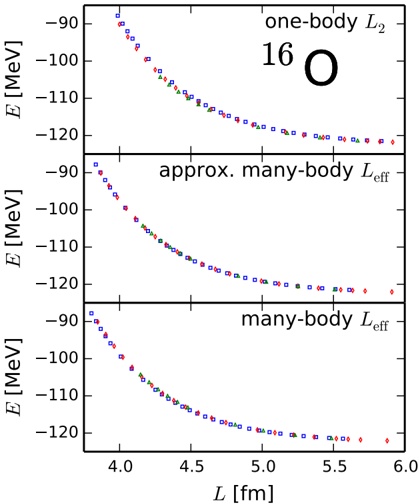

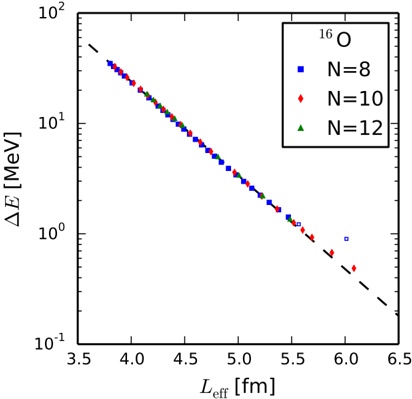

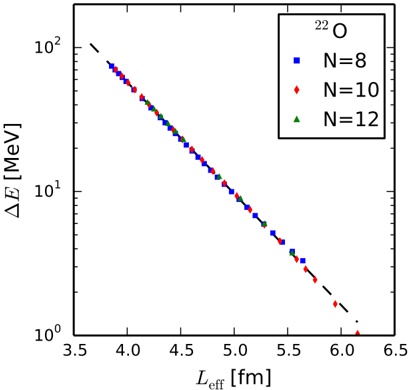

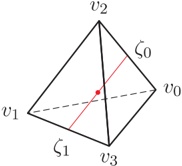

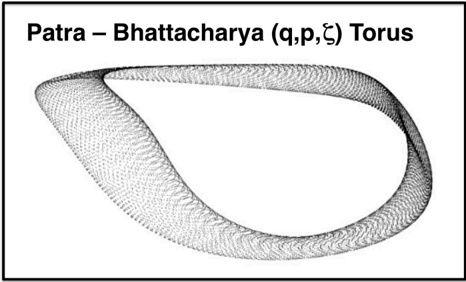

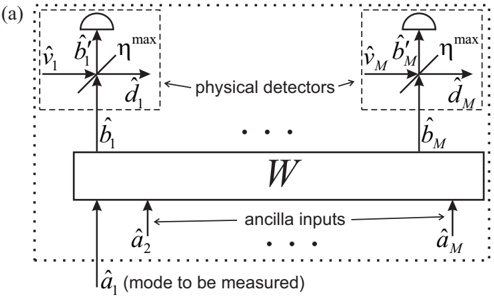

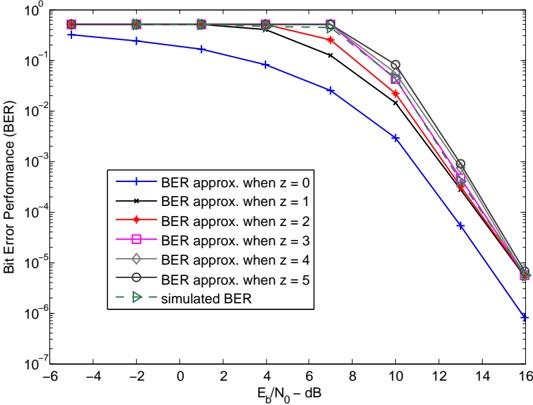

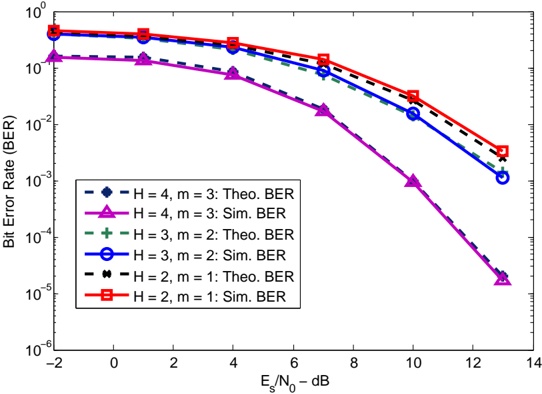

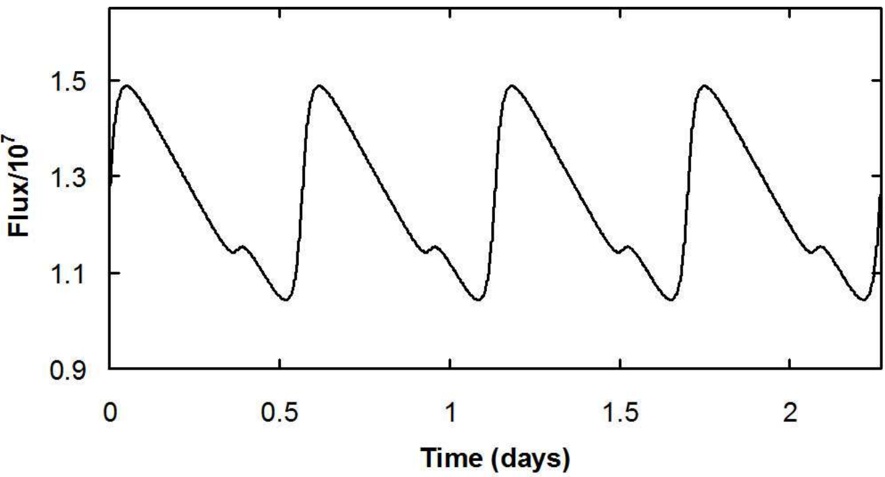

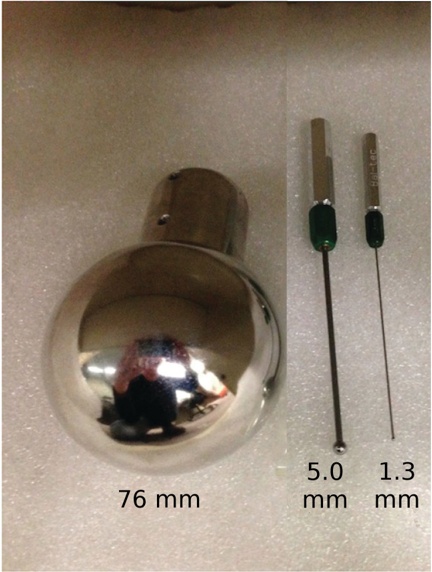

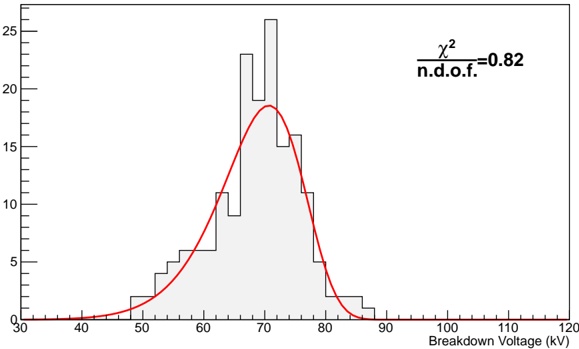

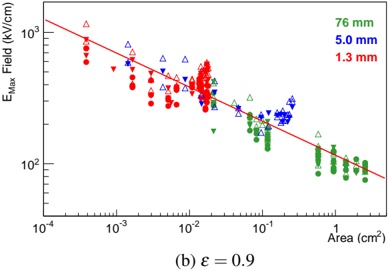

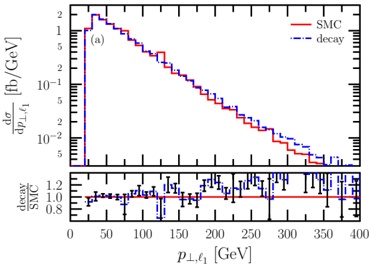

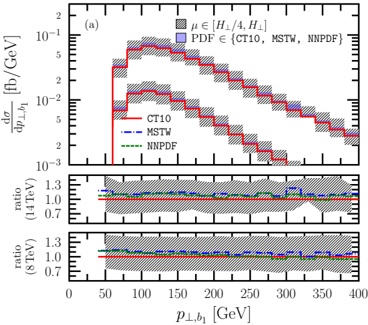

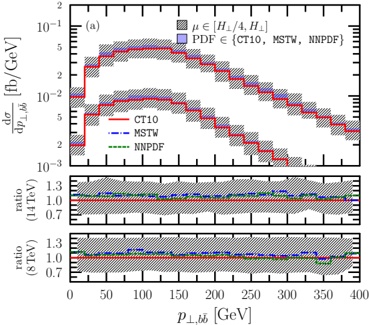

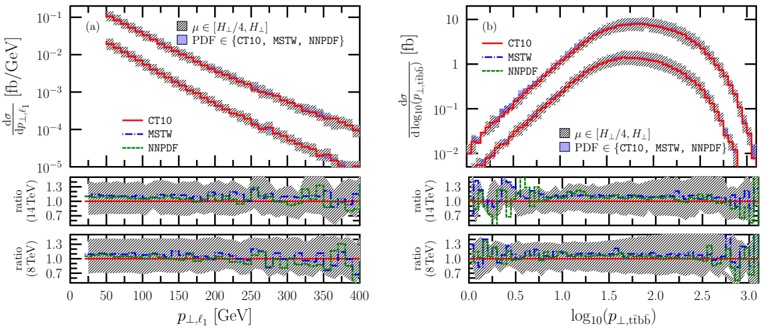

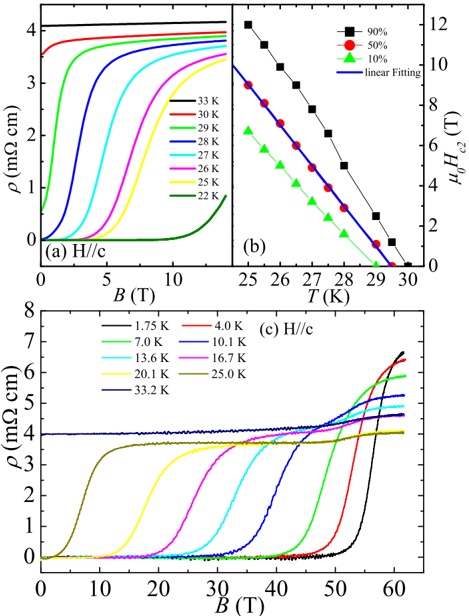

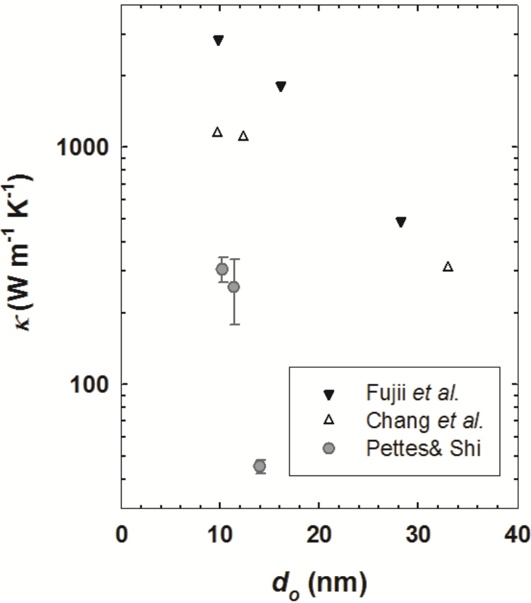

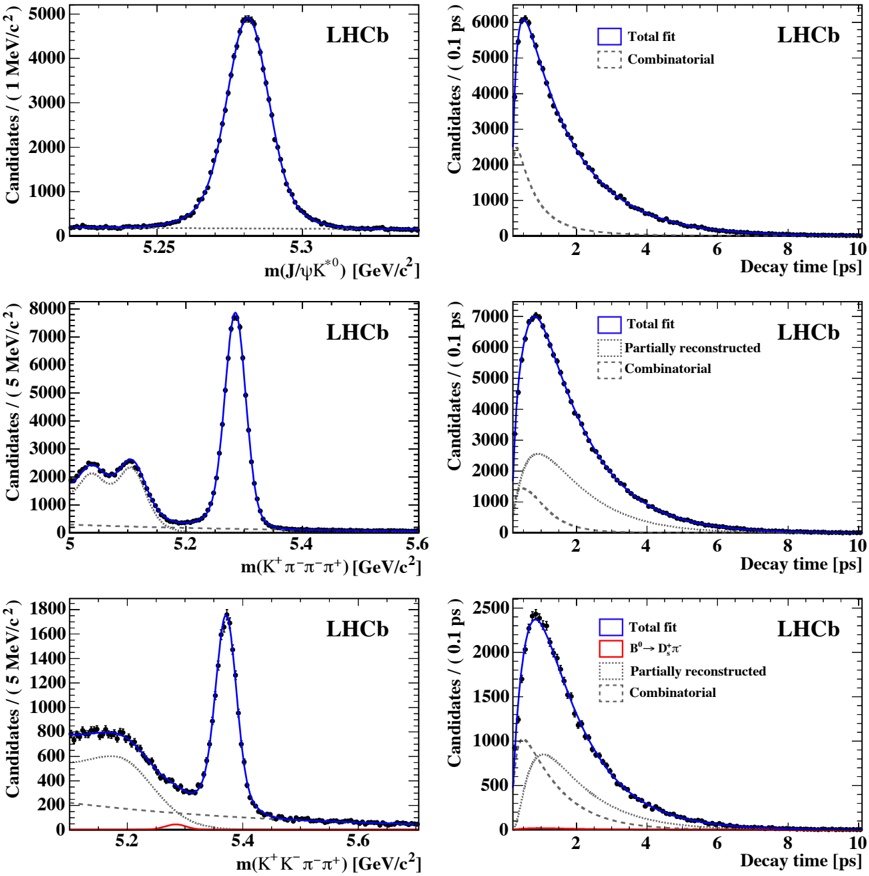

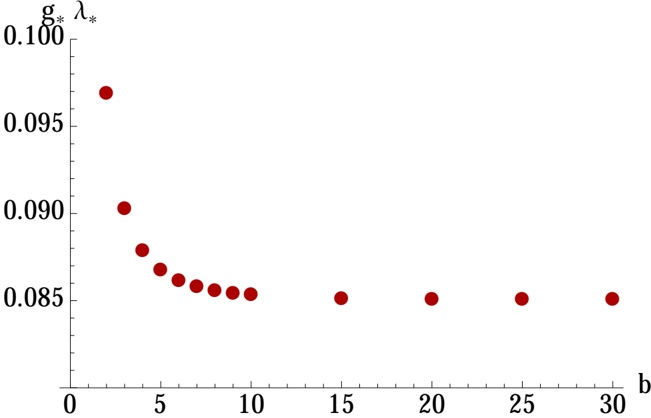

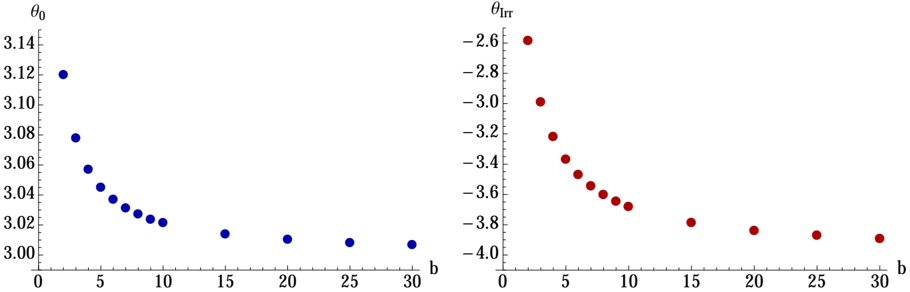

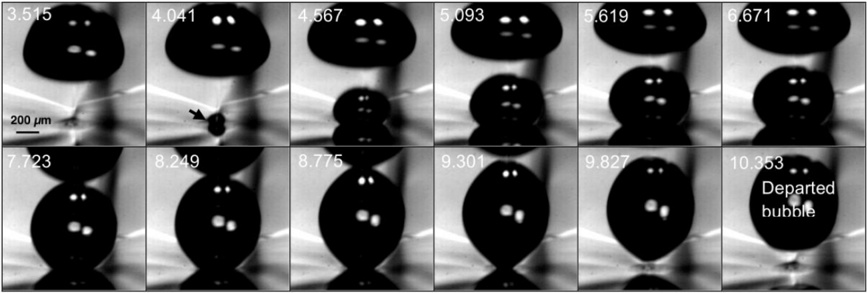

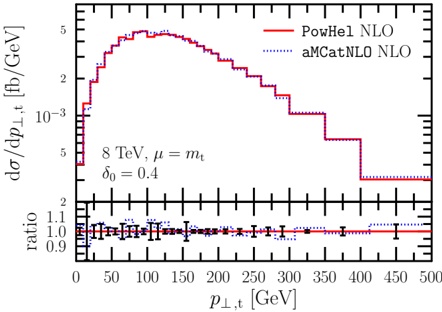

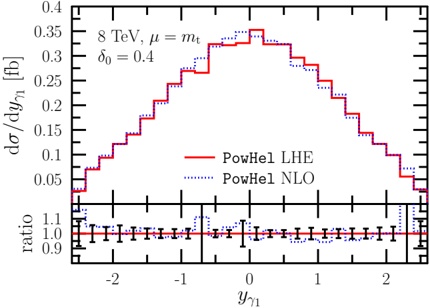

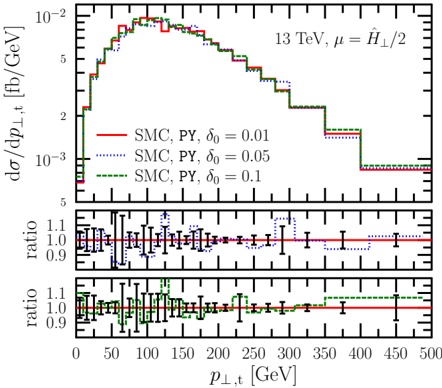

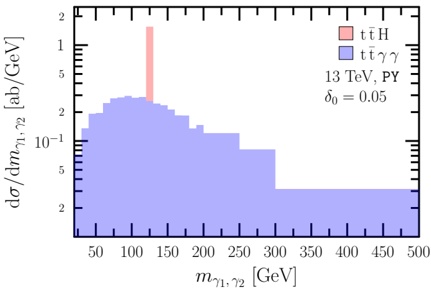

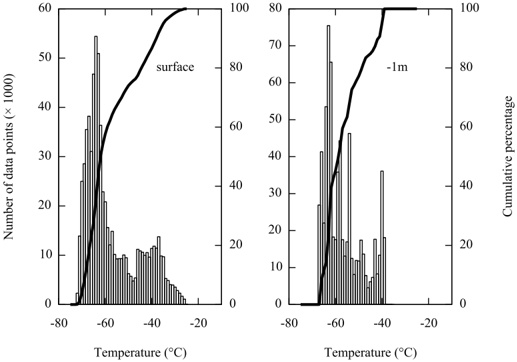

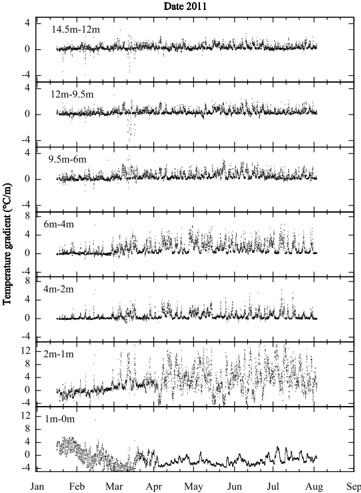

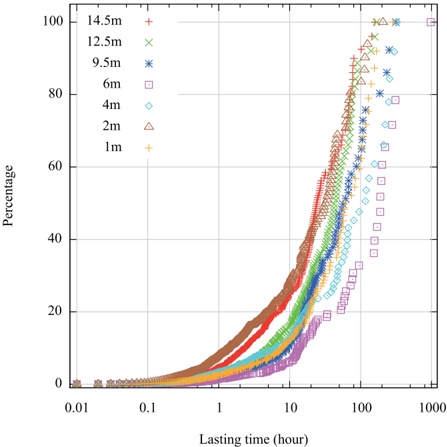

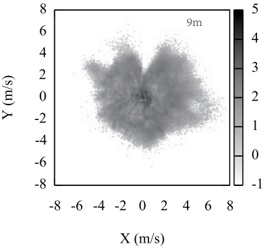

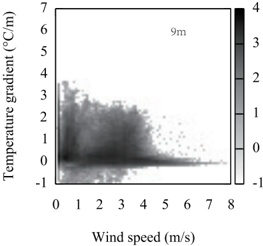

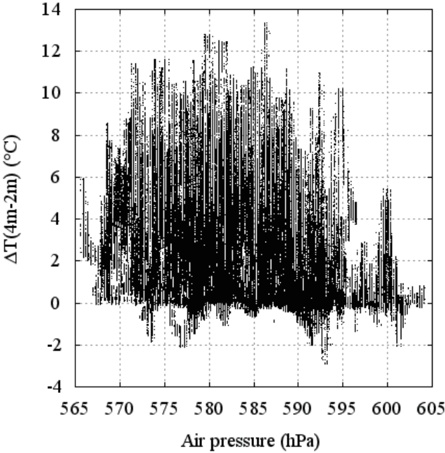

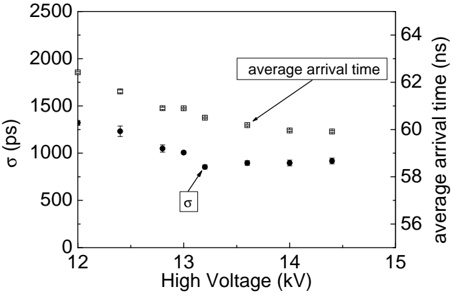

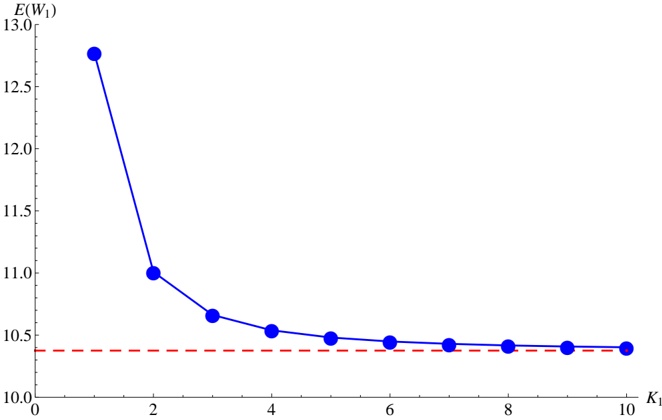

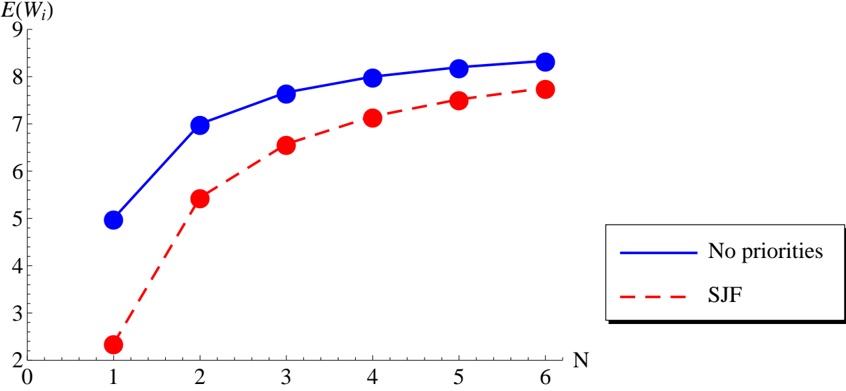

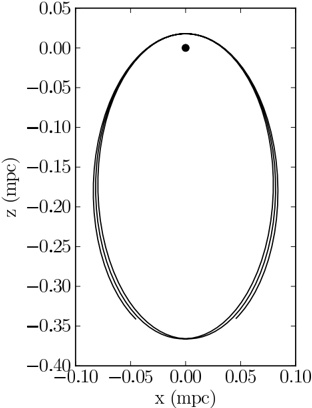

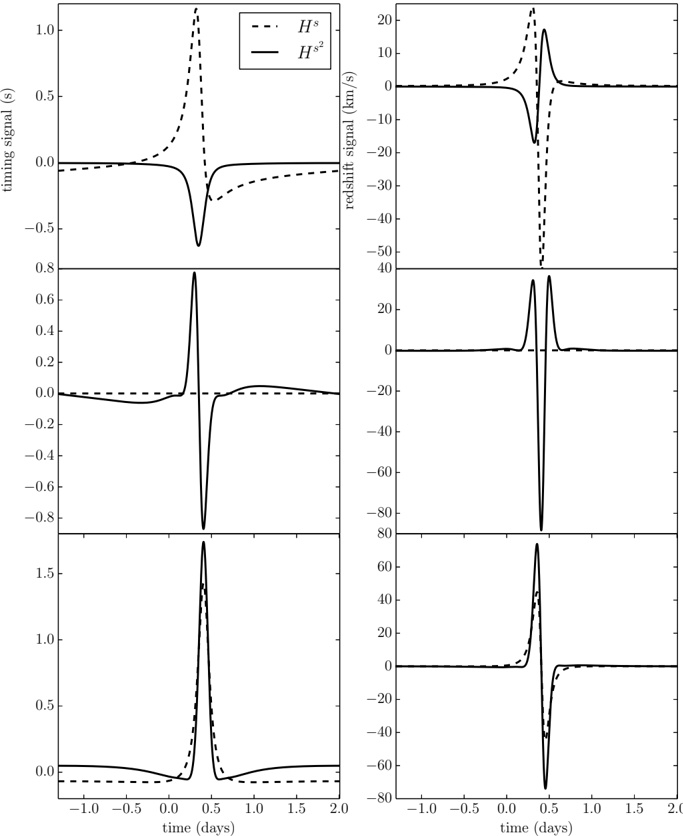

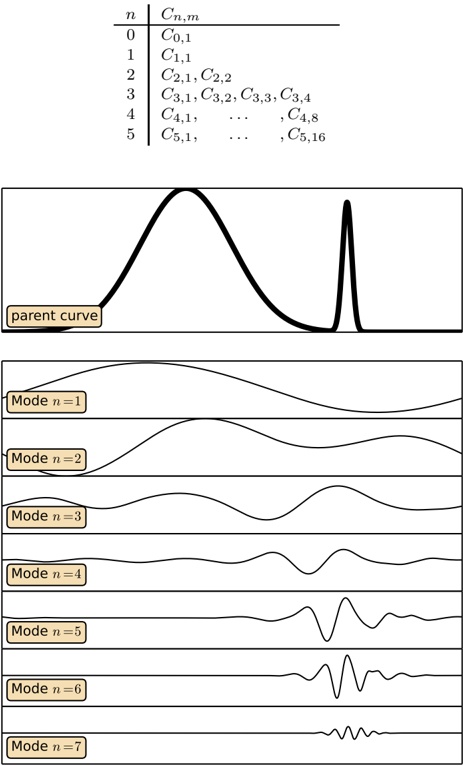

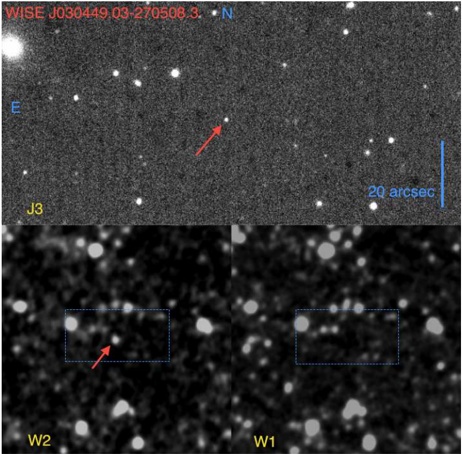

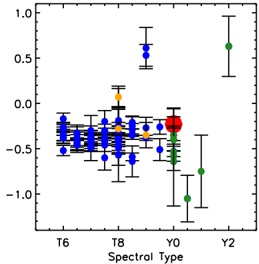

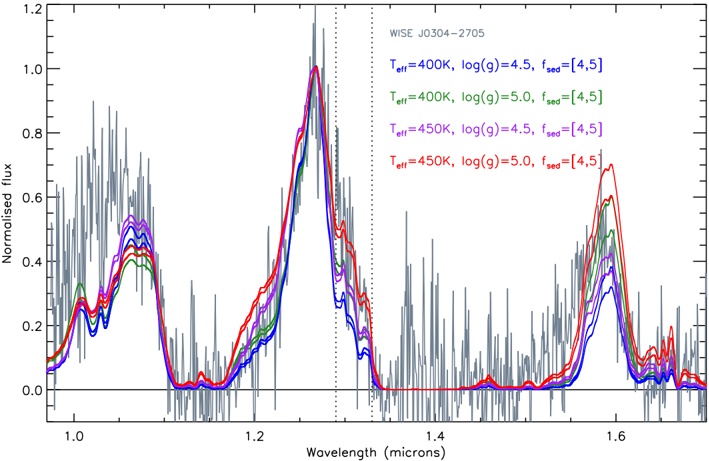

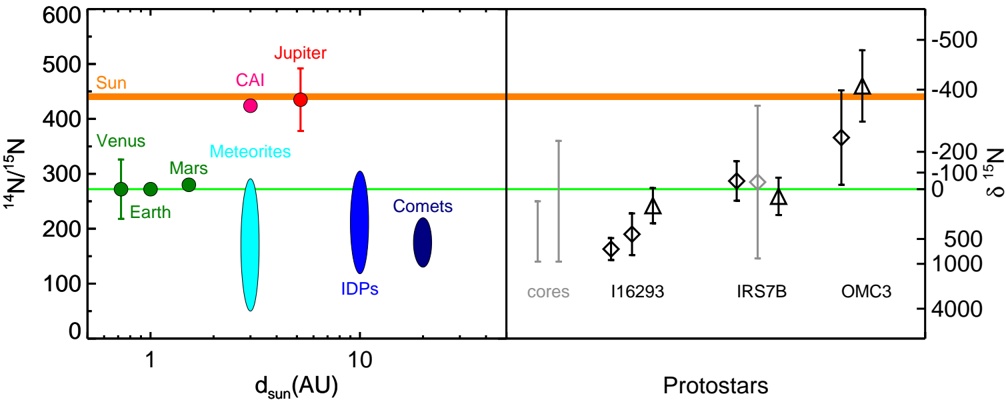

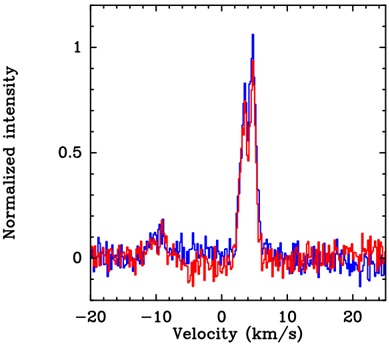

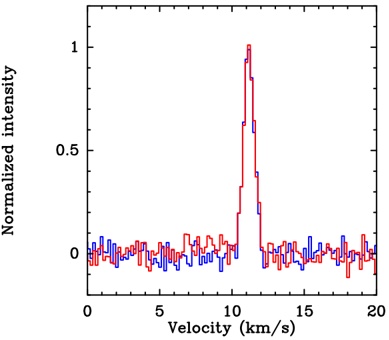

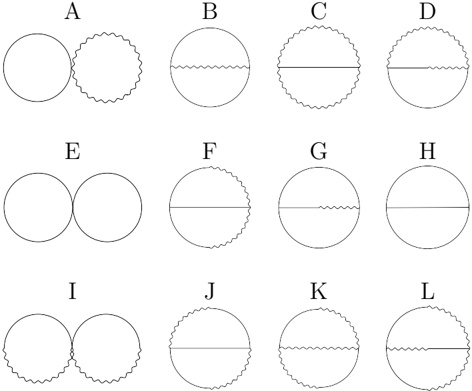

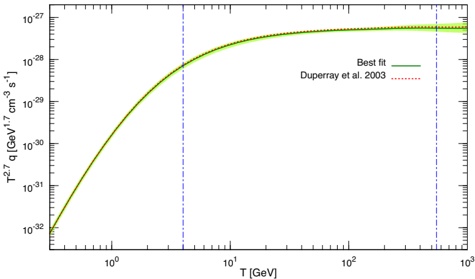

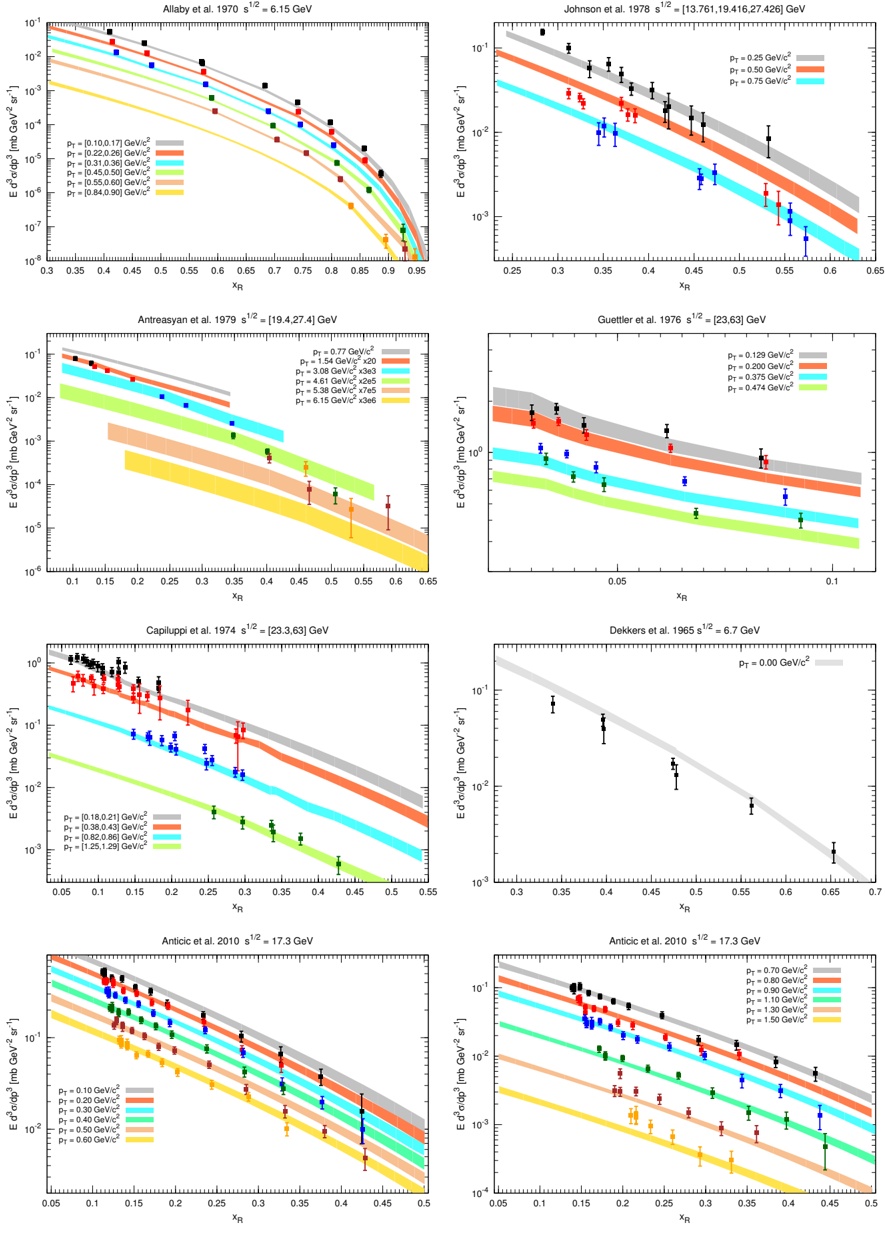

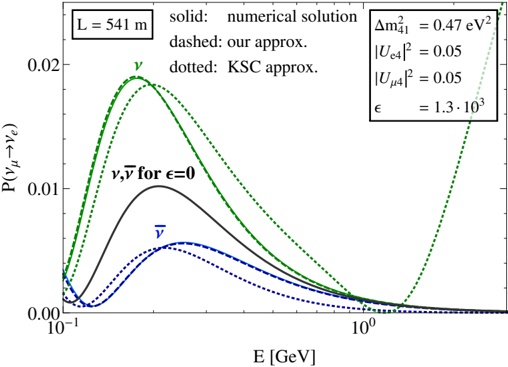

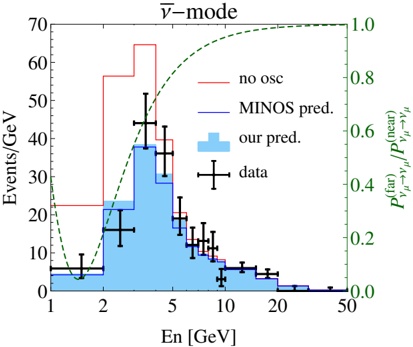

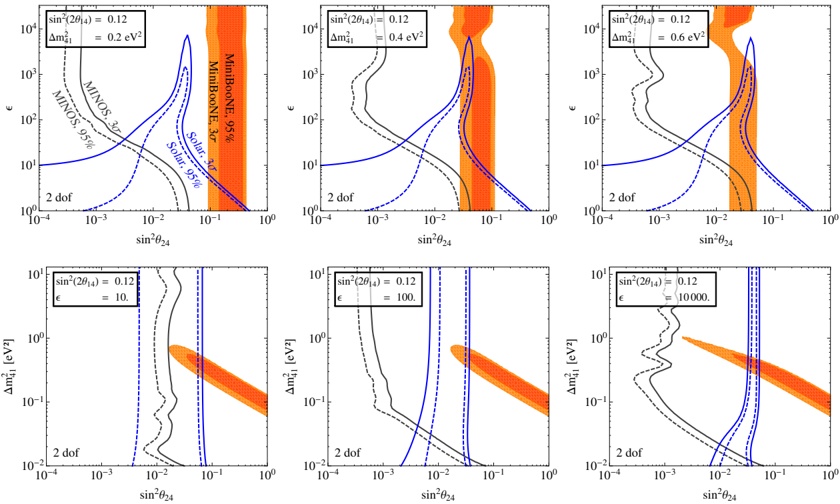

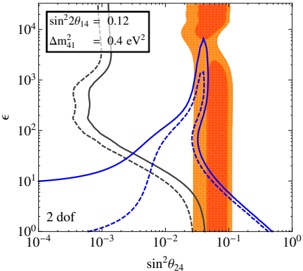

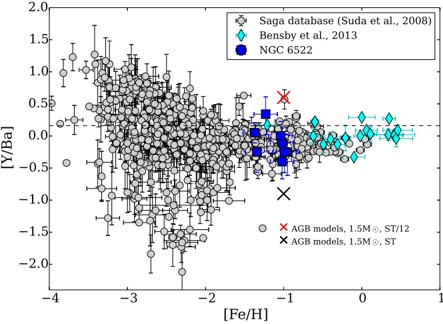

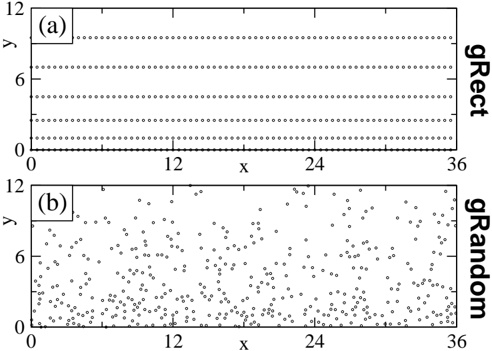

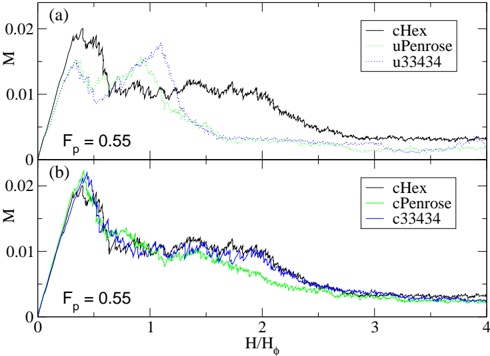

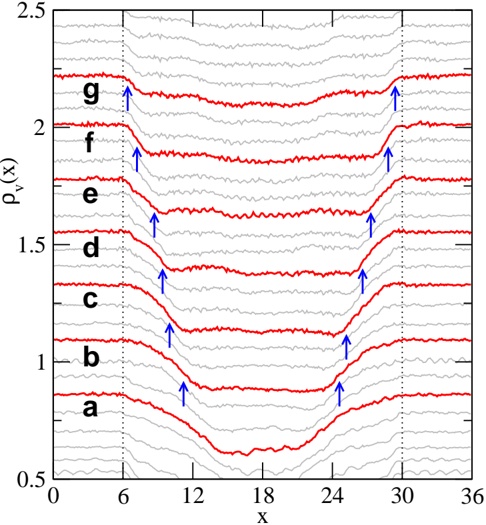

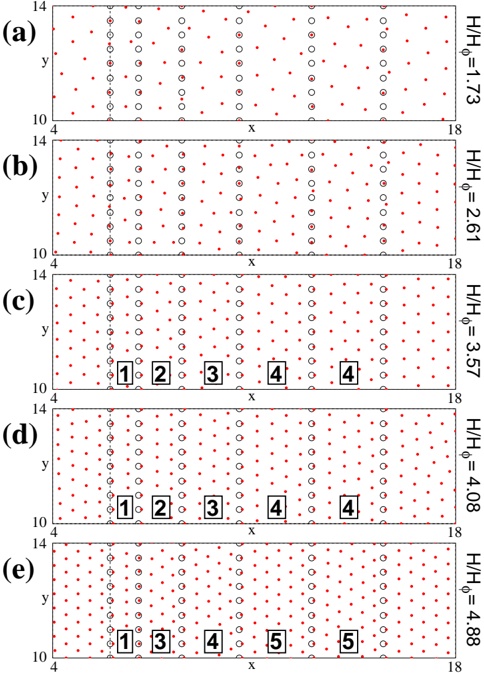

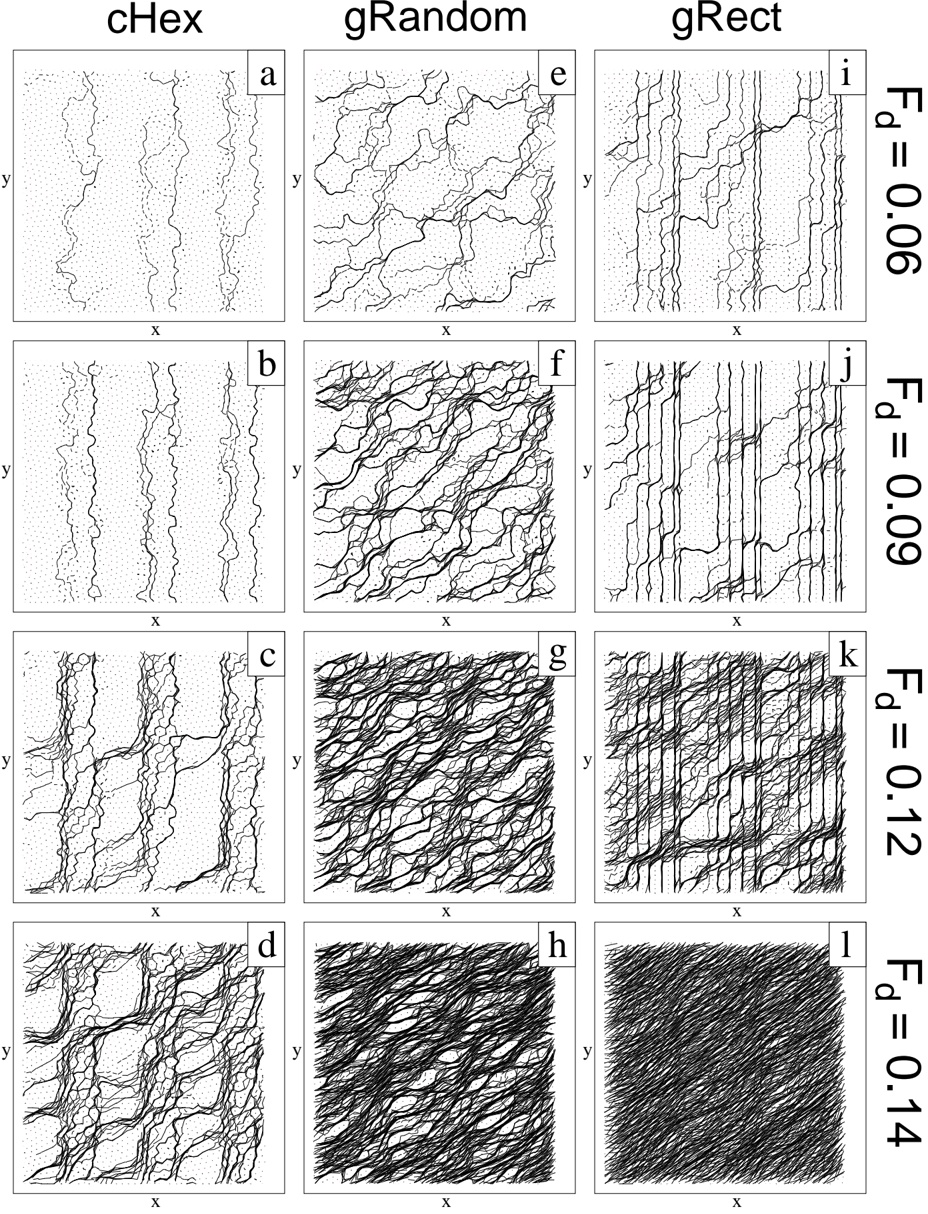

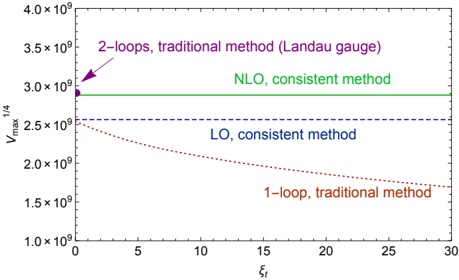

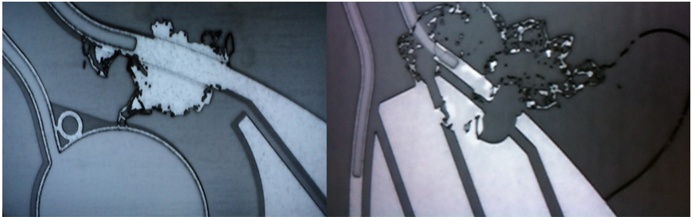

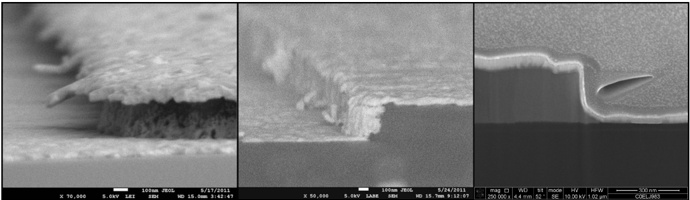

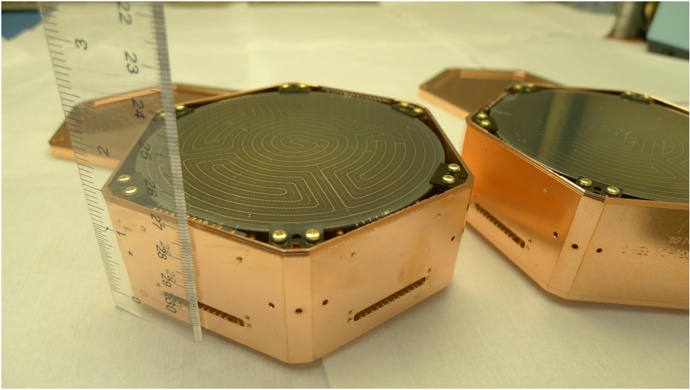

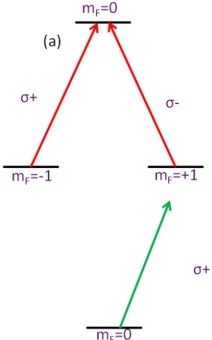

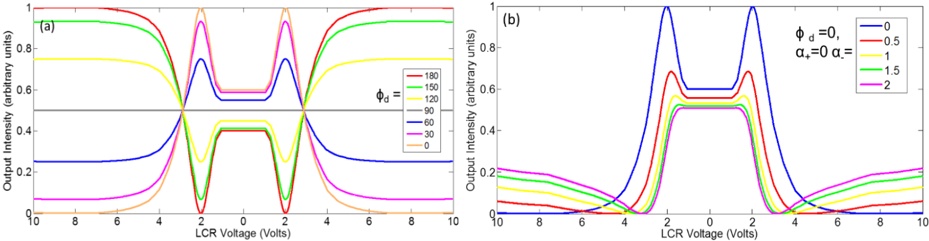

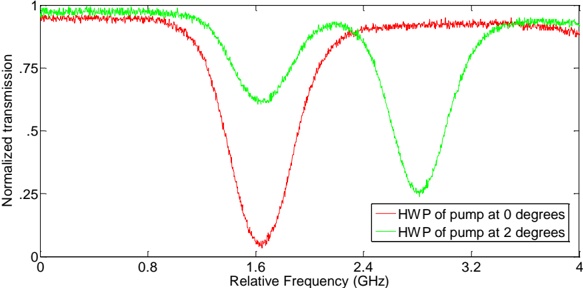

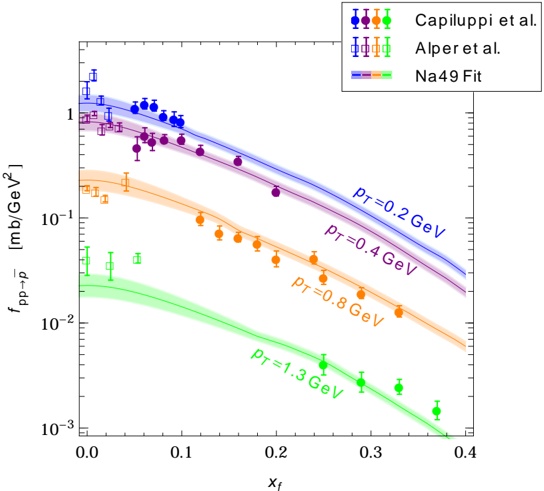

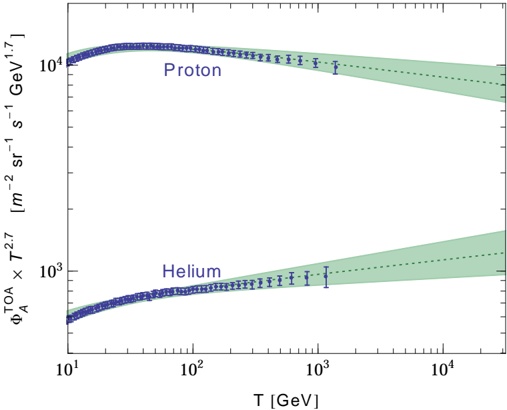

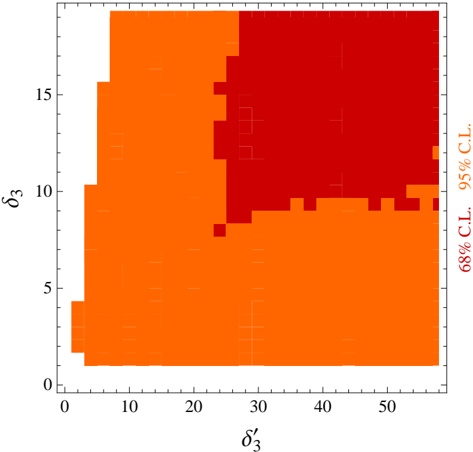

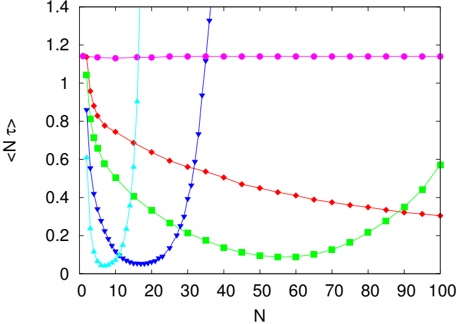

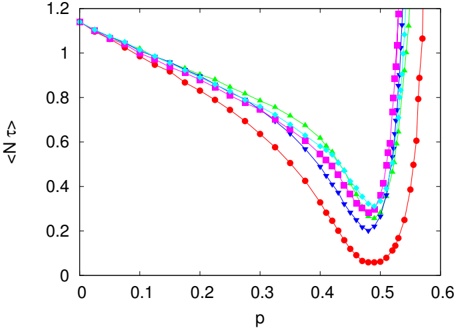

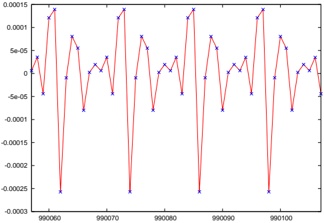

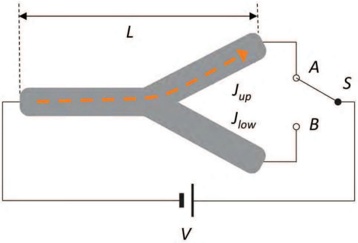

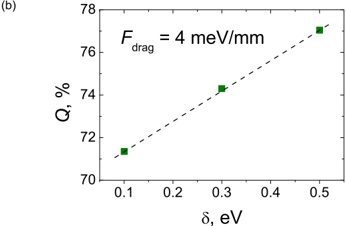

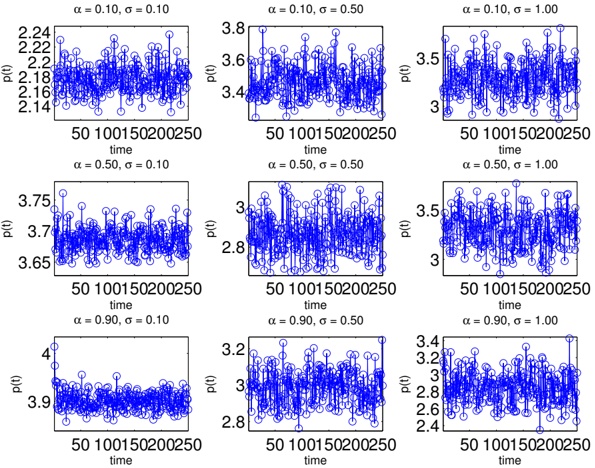

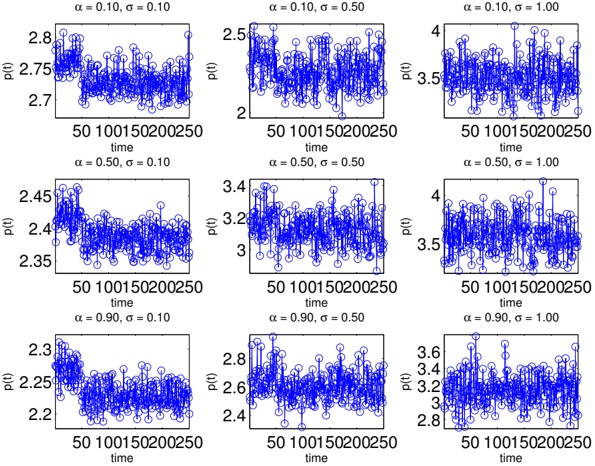

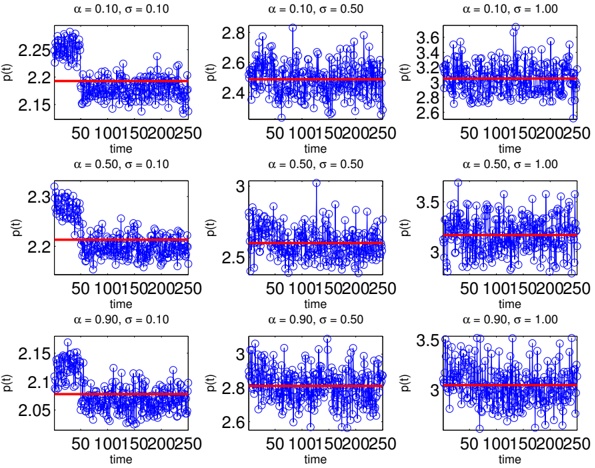

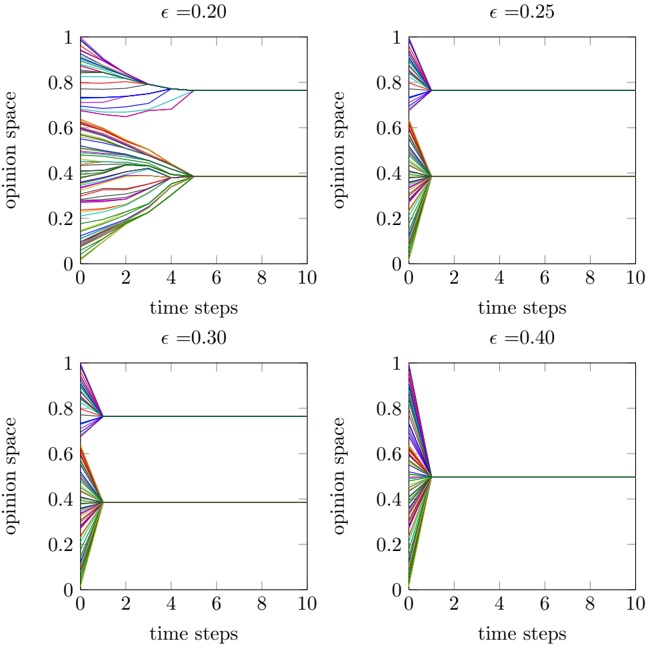

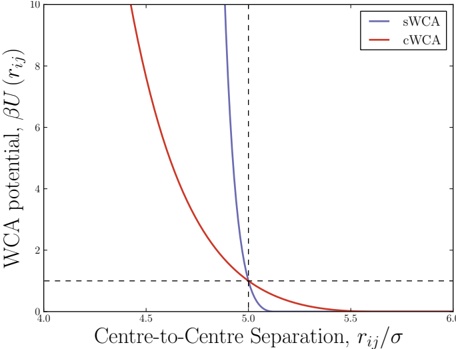

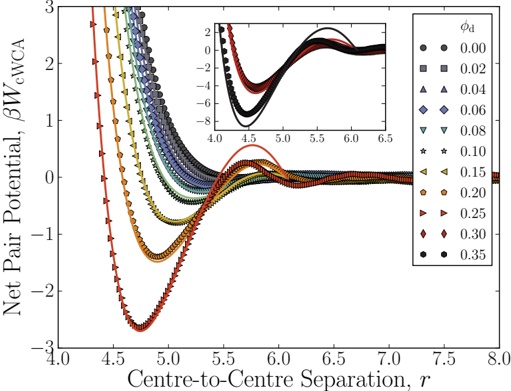

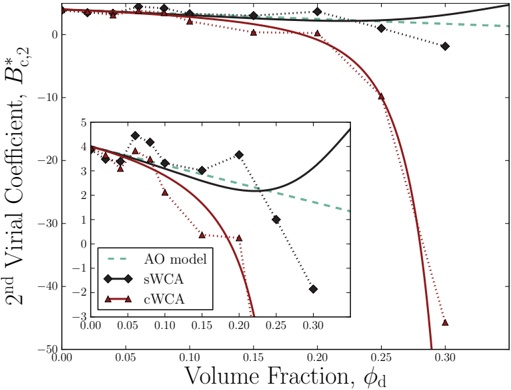

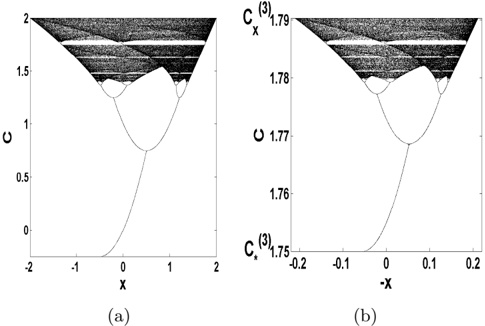

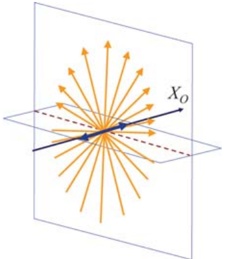

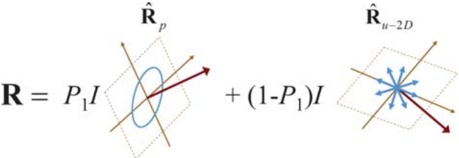

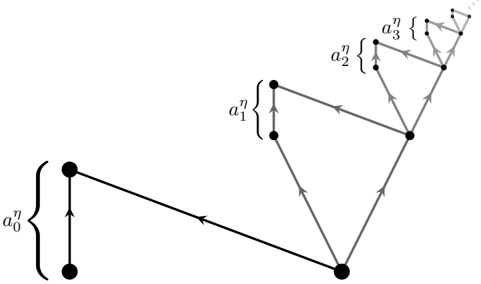

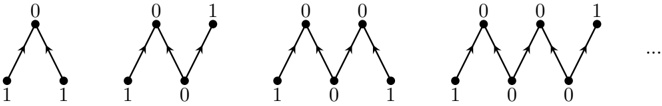

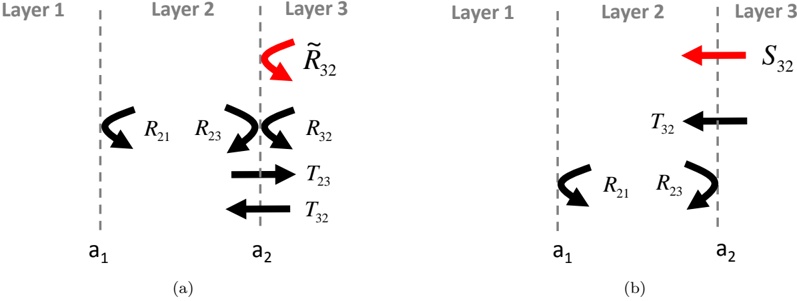

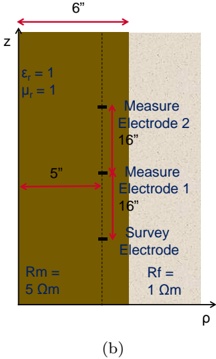

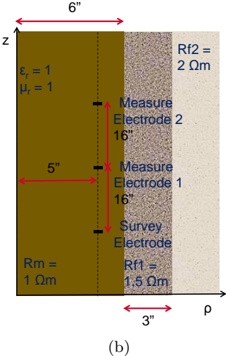

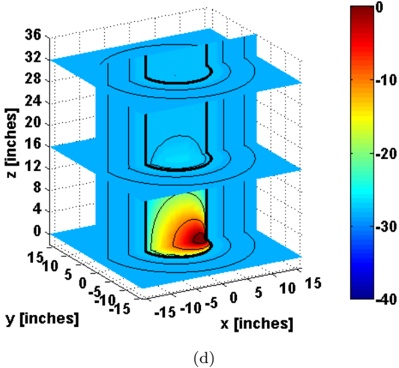

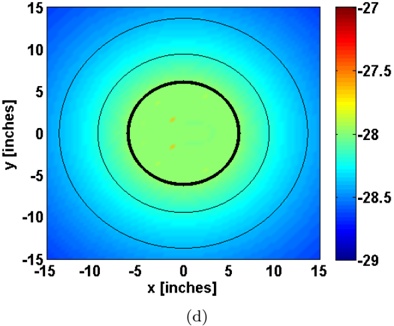

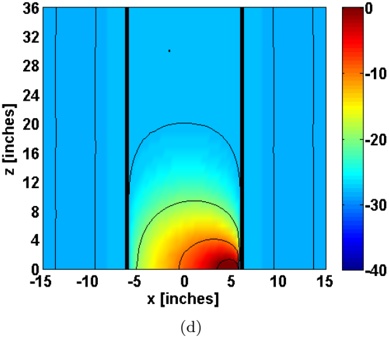

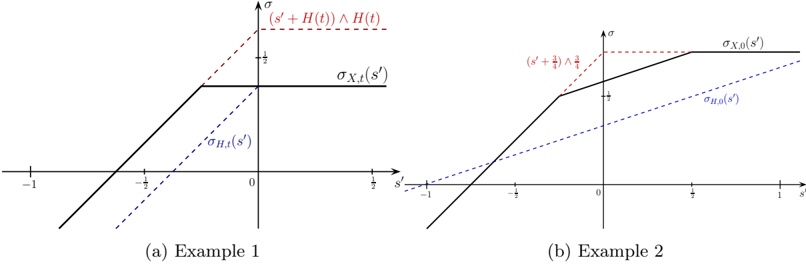

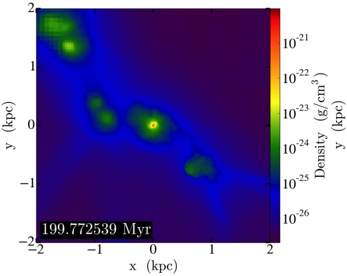

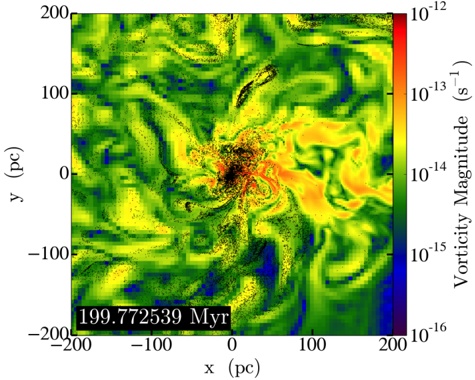

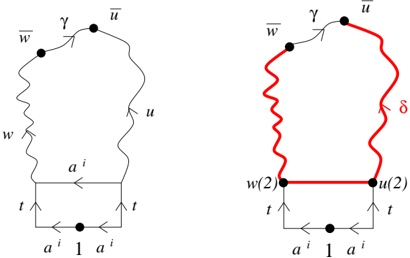

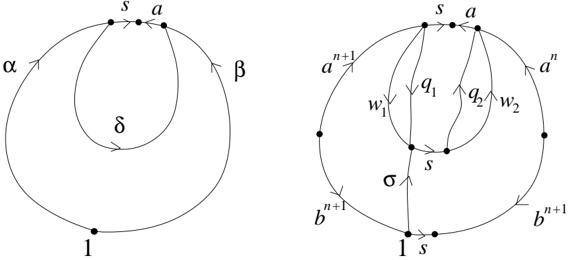

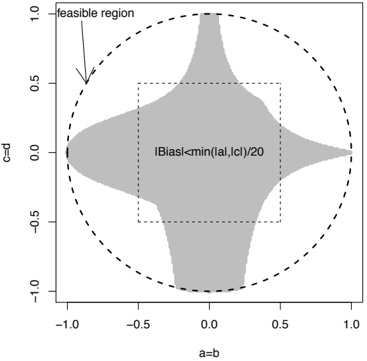

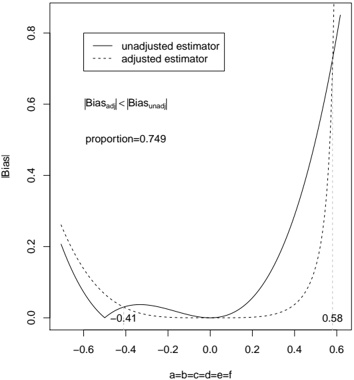

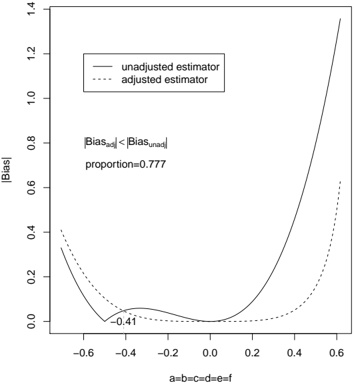

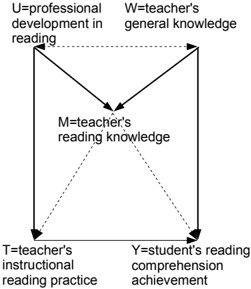

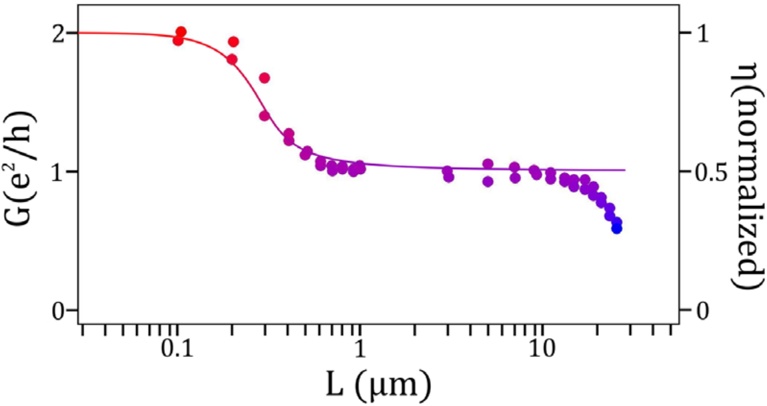

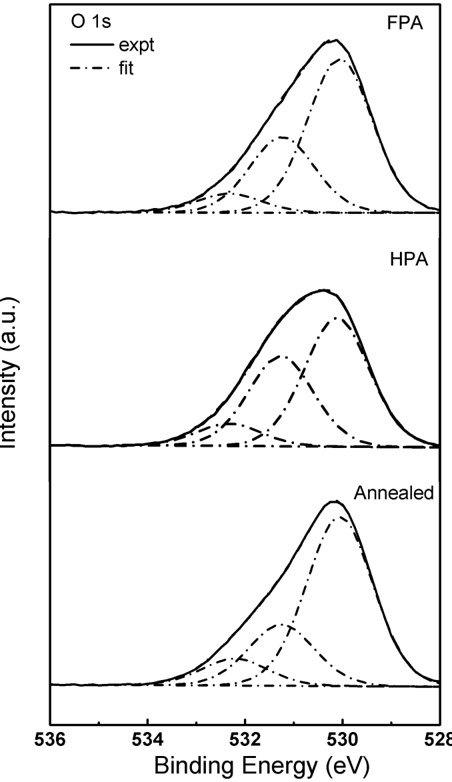

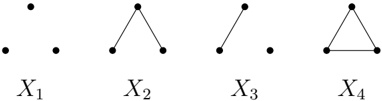

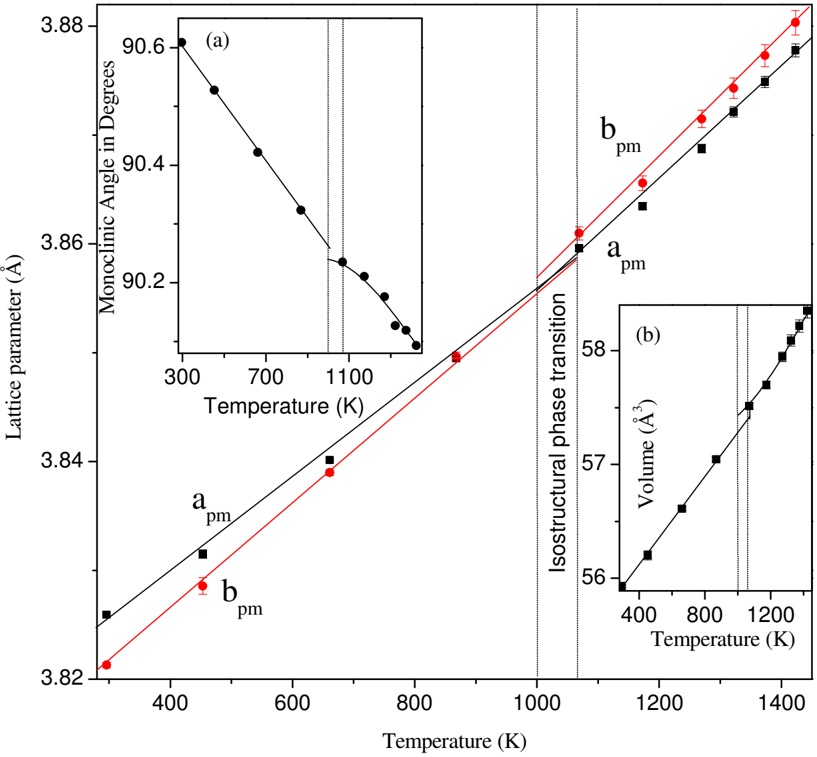

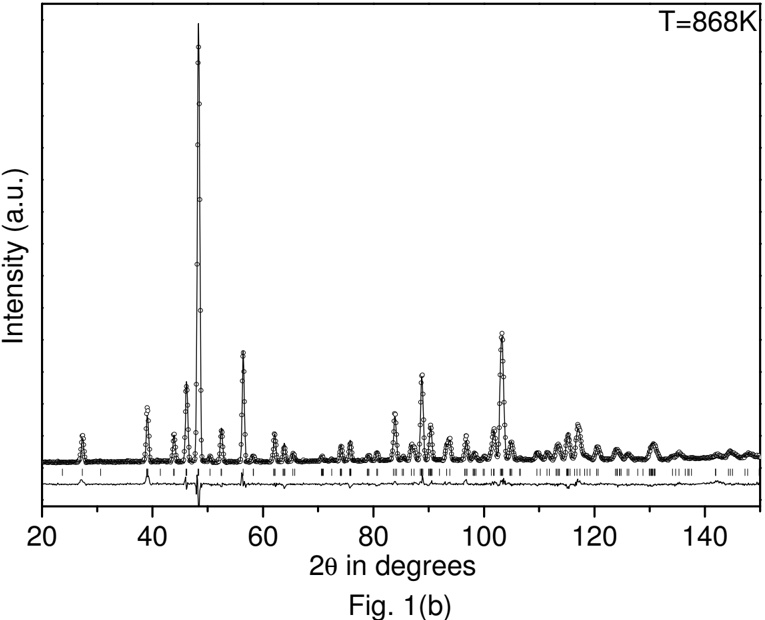

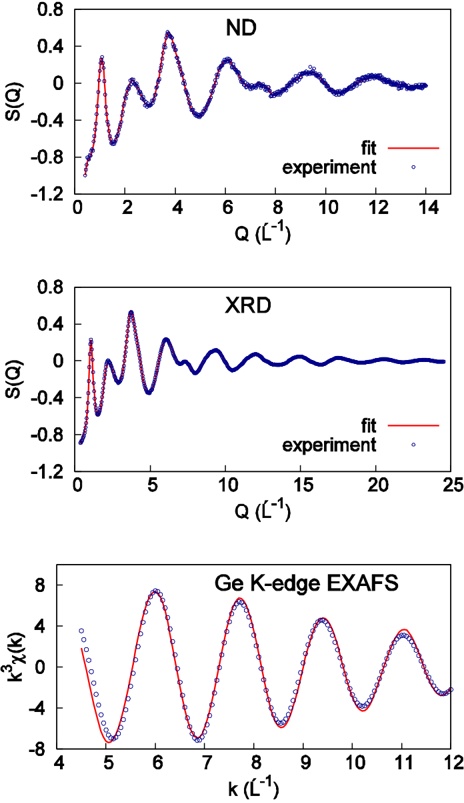

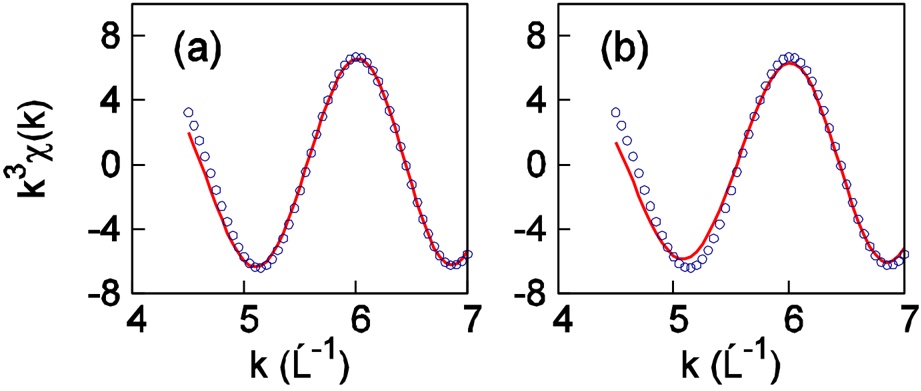

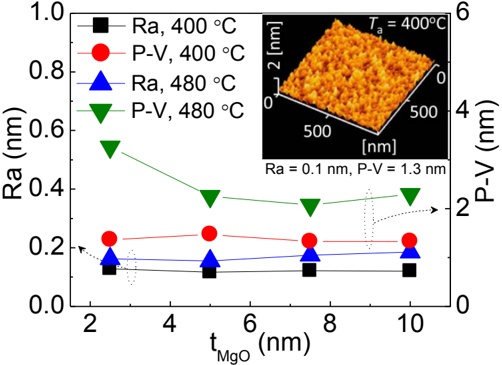

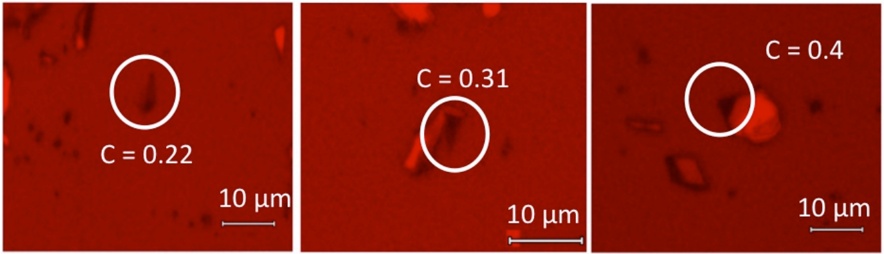

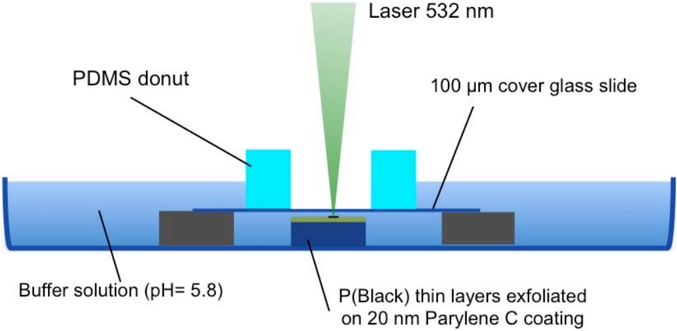

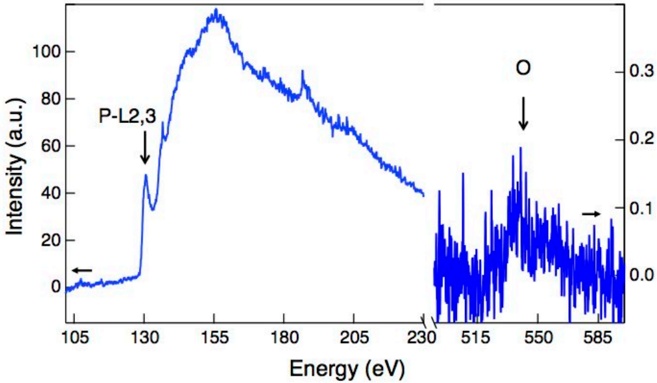

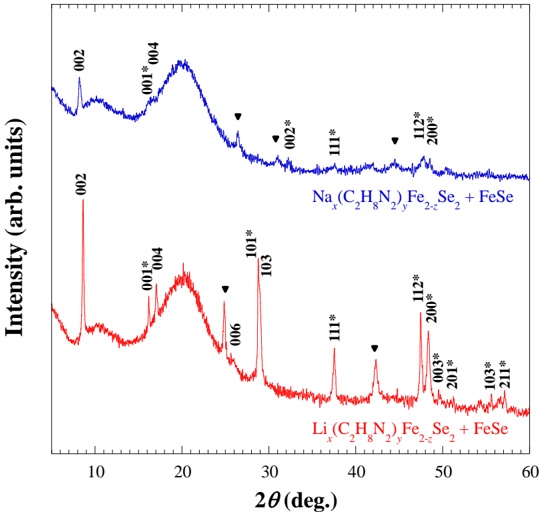

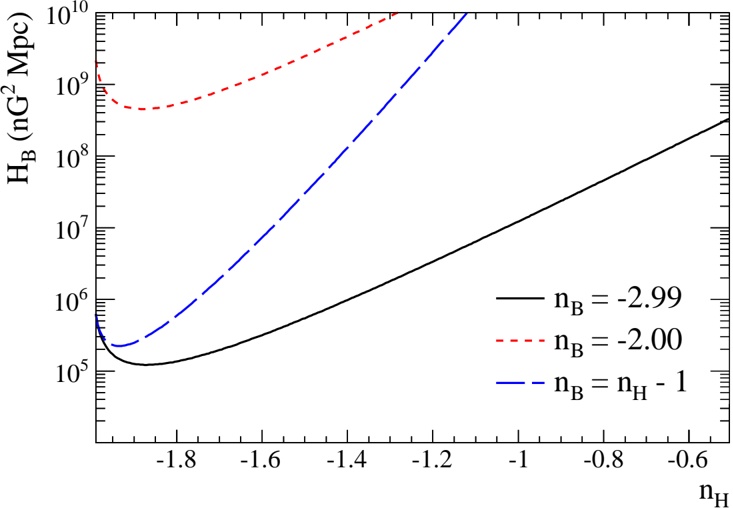

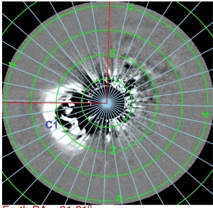

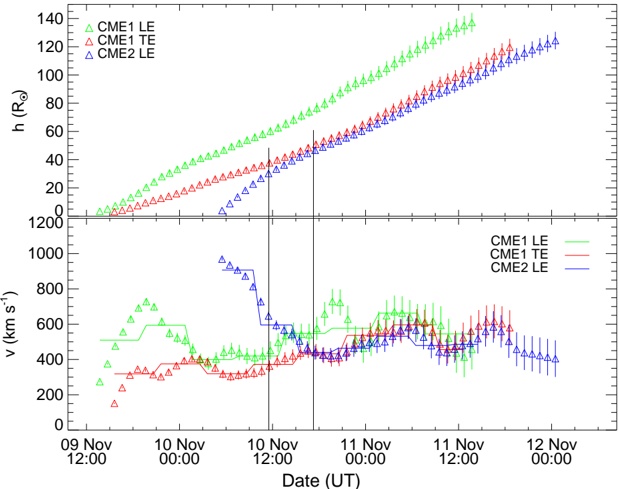

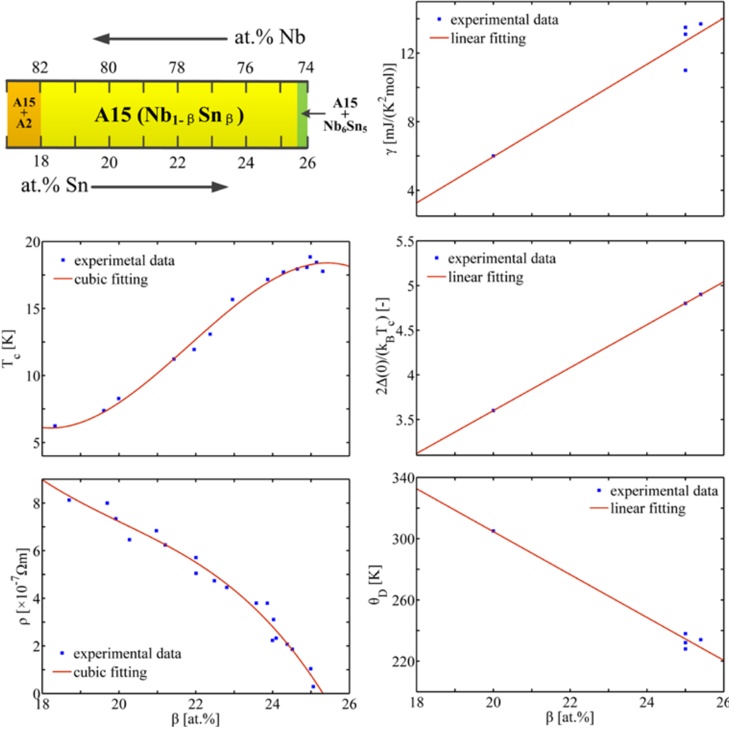

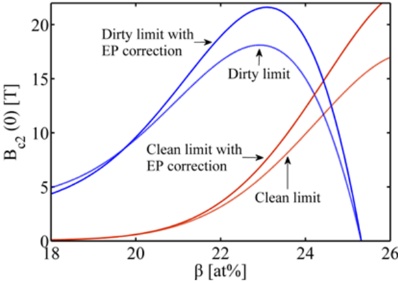

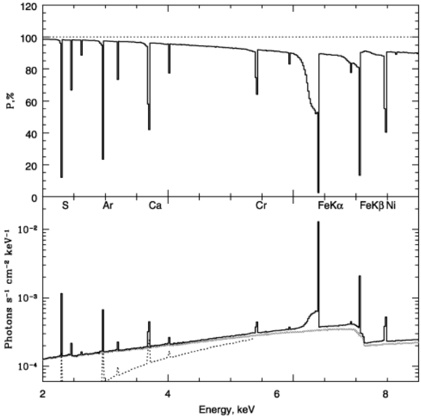

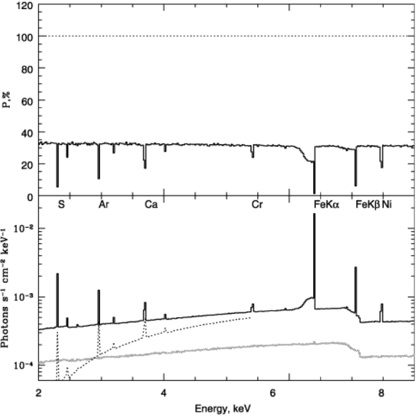

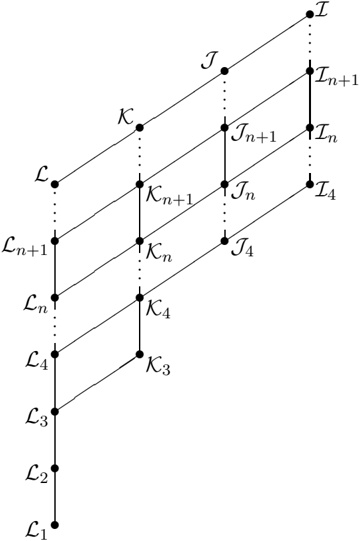

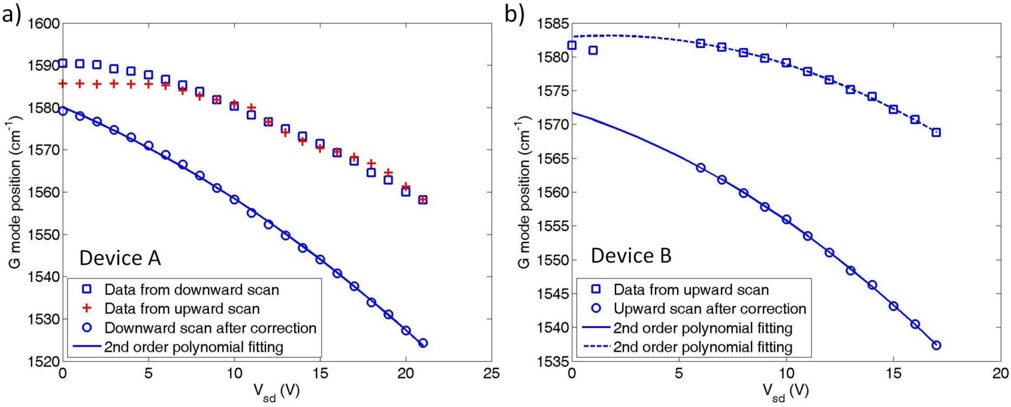

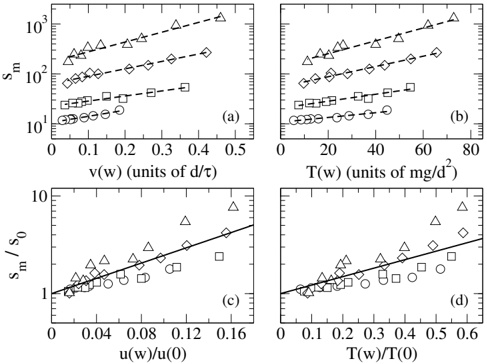

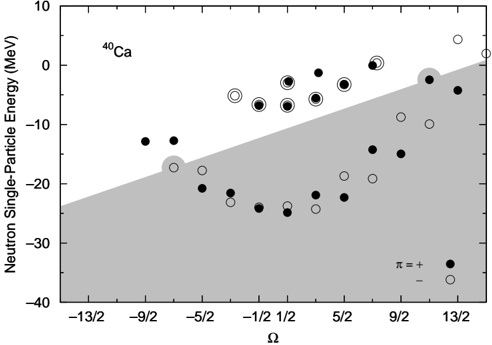

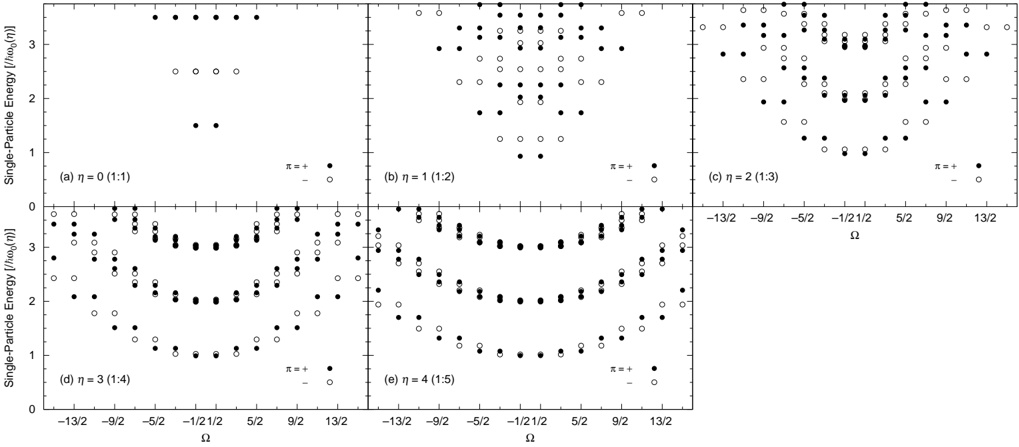

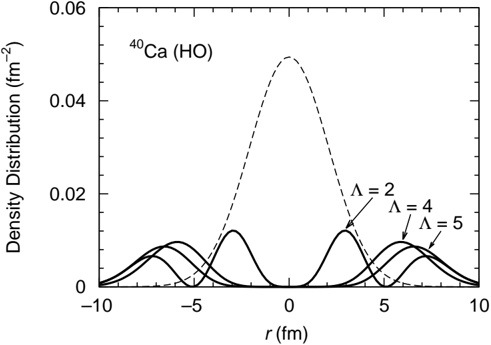

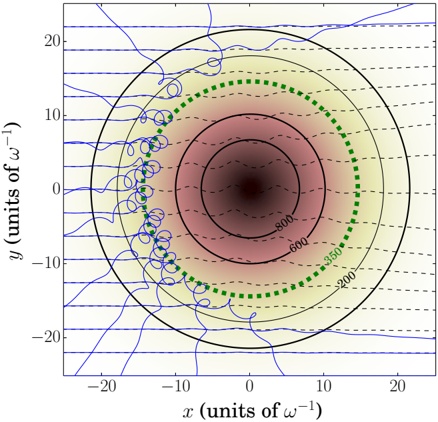

Figure 1. Comparison of the photometry for overlapping sources between Y13 and Phot03. The top row of figures shows V Y13 minus V Phot03 as a function of V Phot03 (left) and as a function of radial distance from the center of the cluster (right). The bottom row shows the same comparisons for I Y13 and I Phot03 . The dashed line in all the figures marks zero difference between the photometry sets.

We will use RV98, K01, Phot98, and Phot03 to refer to each photometry set, respectively. Hole et al. (2009) calibrated each set of photometry to the same zero point as Phot03 and derived the final photometry by averaging all V and ( B -V ) information available for each star from RV98, Phot98, Phot03, and K01 (more details available in Hole et al. 2009, and references therein). This provided BV photometry for 2220 stars in our sample, yet left a large number of stars, especially in the outer part of the field, with no BV information. Recent photometry of Yang et al. (2013) and Everett, Howell & Kinemuchi (2012), hereafter Y13 and EHK12 respectively, include almost all the stars in our NGC 6819 sample. We have used these photometry sets to revise and expand the photometry for the stars in our RV survey.

## 2.1. Yang et al. (2013)

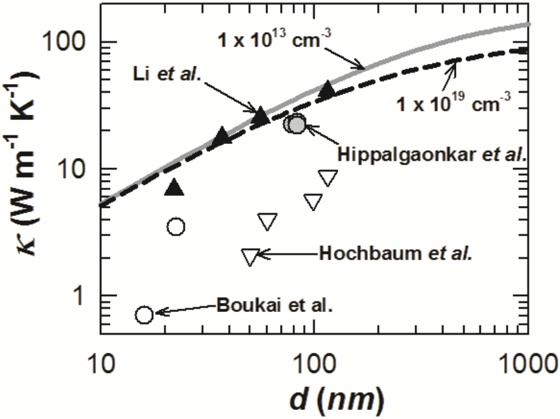

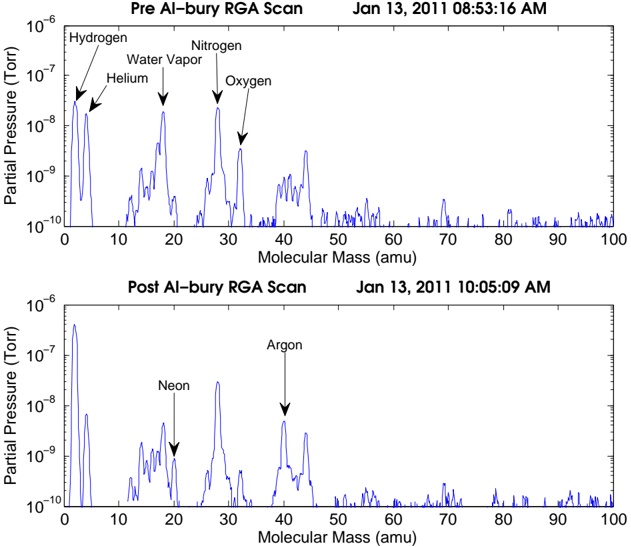

Y13 provides CCD V I photometry for 3831 stars in our RV sample and covers the entire radial extent of our survey. The data were taken in 2000 July on the WIYN 0.9 m telescope with the NOAO MOSAIC imager at the f /7.5 secondary and provided a field of view of approximately 1 ◦ × 1 . ◦ Yang et al. (2013) used Phot03 to calibrate their instrumental magnitudes and therefore Y13 and Phot03 have no significant offsets. This is seen in Figure 1 and in the average differences, 〈 V Y13 -V Phot03 〉 = 0.005 ± 0.001 and 〈 I Y13 -I Phot03 〉 = 0.000 ± 0.001. The I band shows a larger range in the scatter between Phot03 (root-mean-square error of 0.039) and Y13 than the V band (rms error of 0.036), but neither band has a dependence on magnitude except in I for the very brightest stars.

## 2.2. Everett, Howell & Kinemuchi (2012)

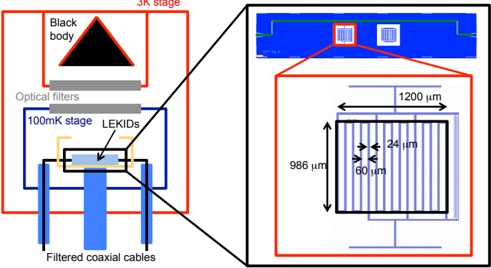

EHK12 provides UBV photometry of 4 414 002 , , sources in the Kepler field, including NGC 6819. They observed the Kepler field using the NOAO Mosaic-1.1 Wide Field Imager and the WIYN 0.9 m telescope with a set of 209 pointings over five nights in 2011 June and achieved typical completeness limits of U ∼ 18.7, B ∼ 19.3, and V ∼ 19.1, well below the magnitude limits of our target sample.

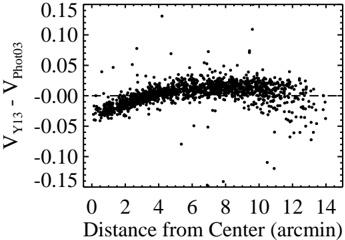

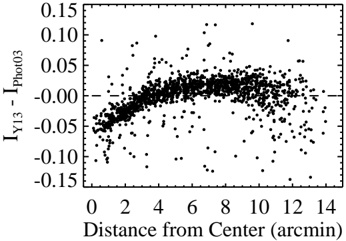

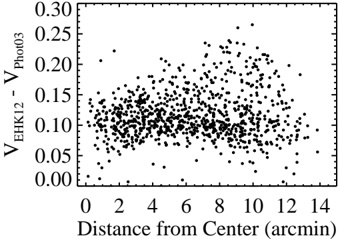

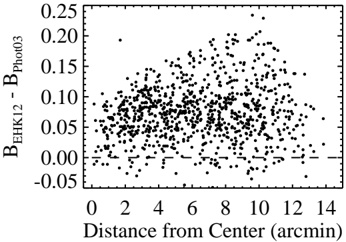

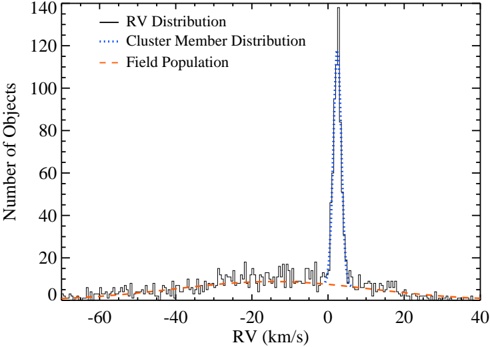

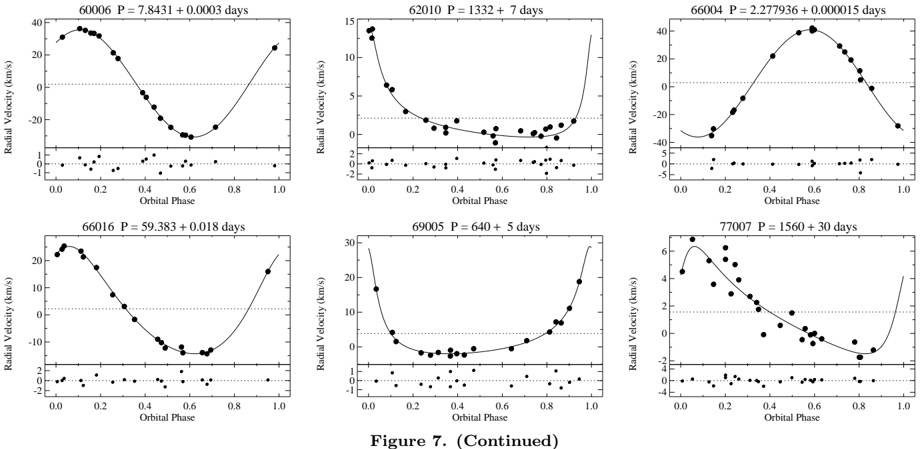

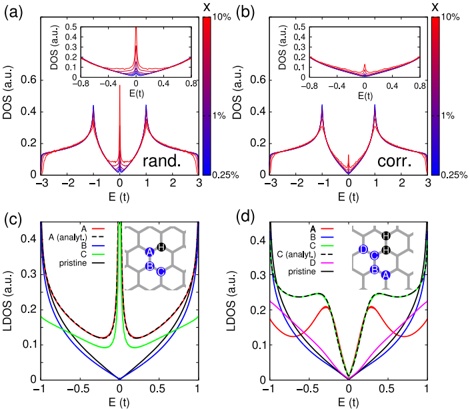

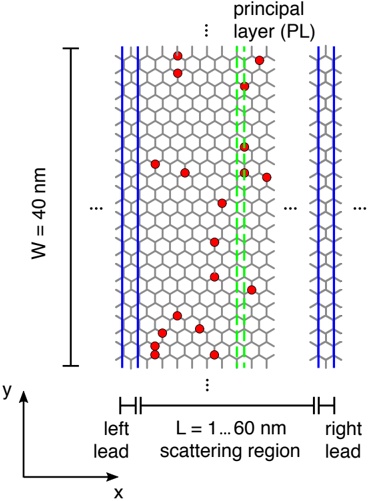

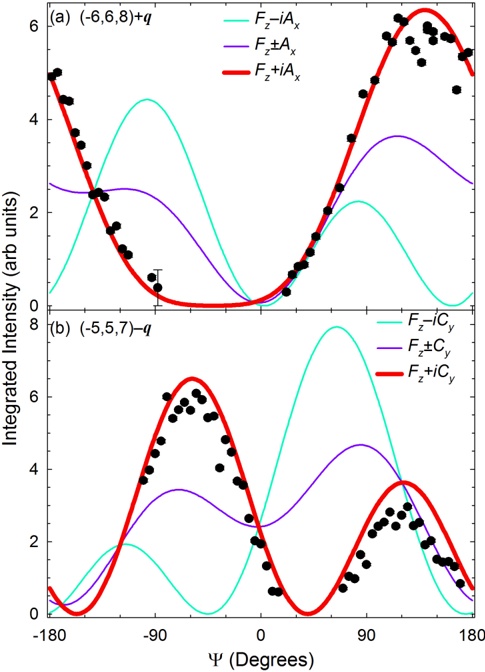

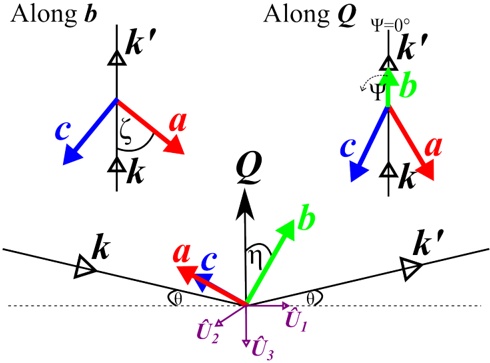

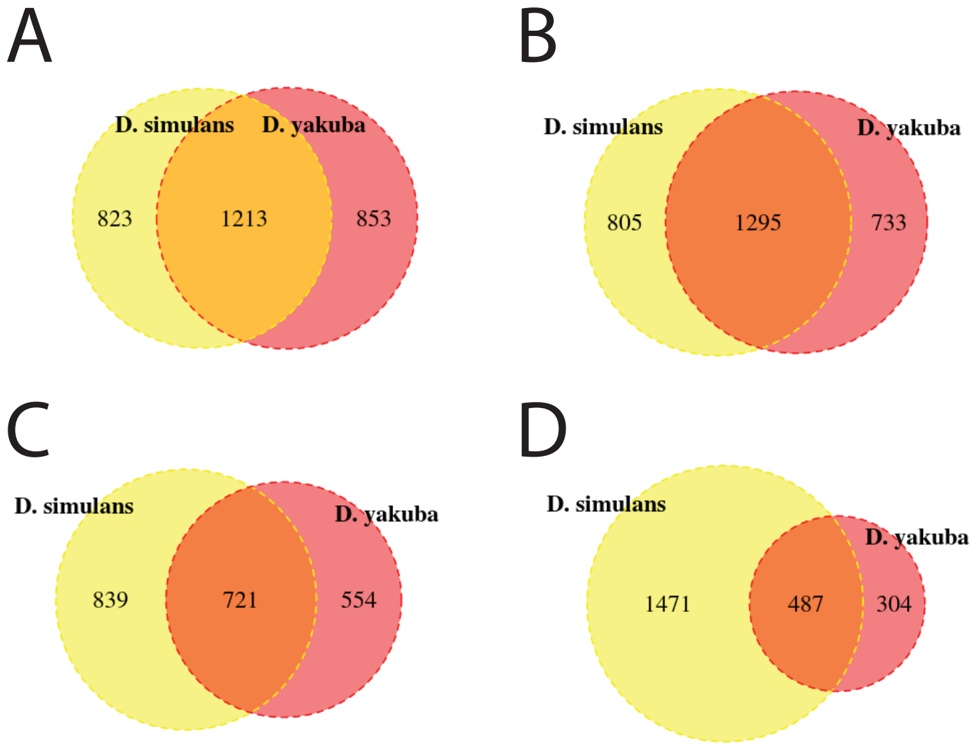

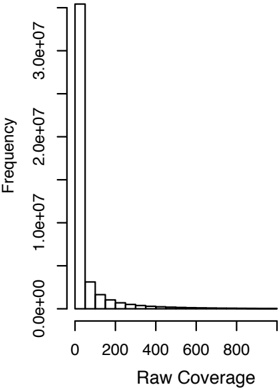

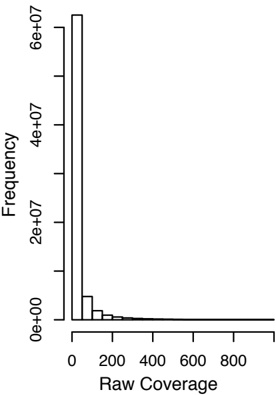

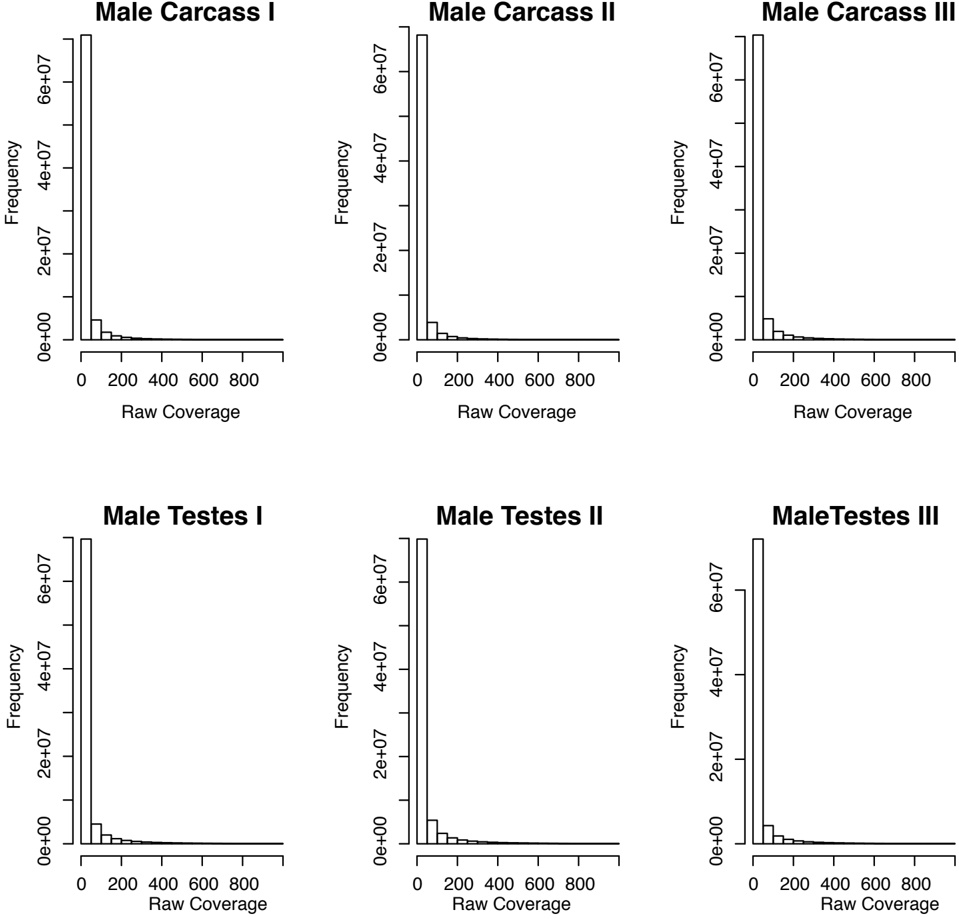

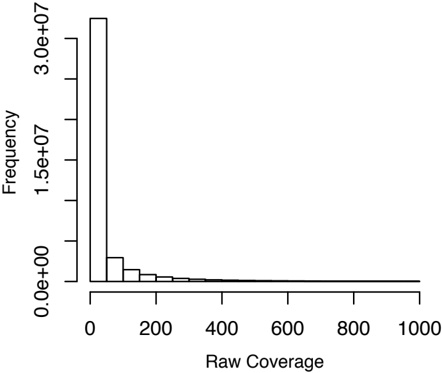

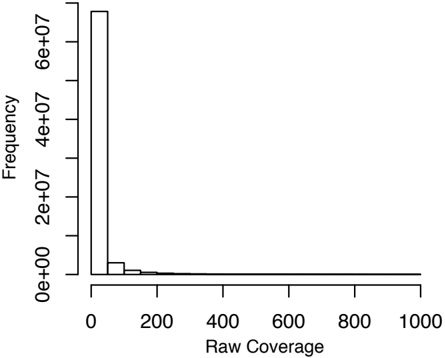

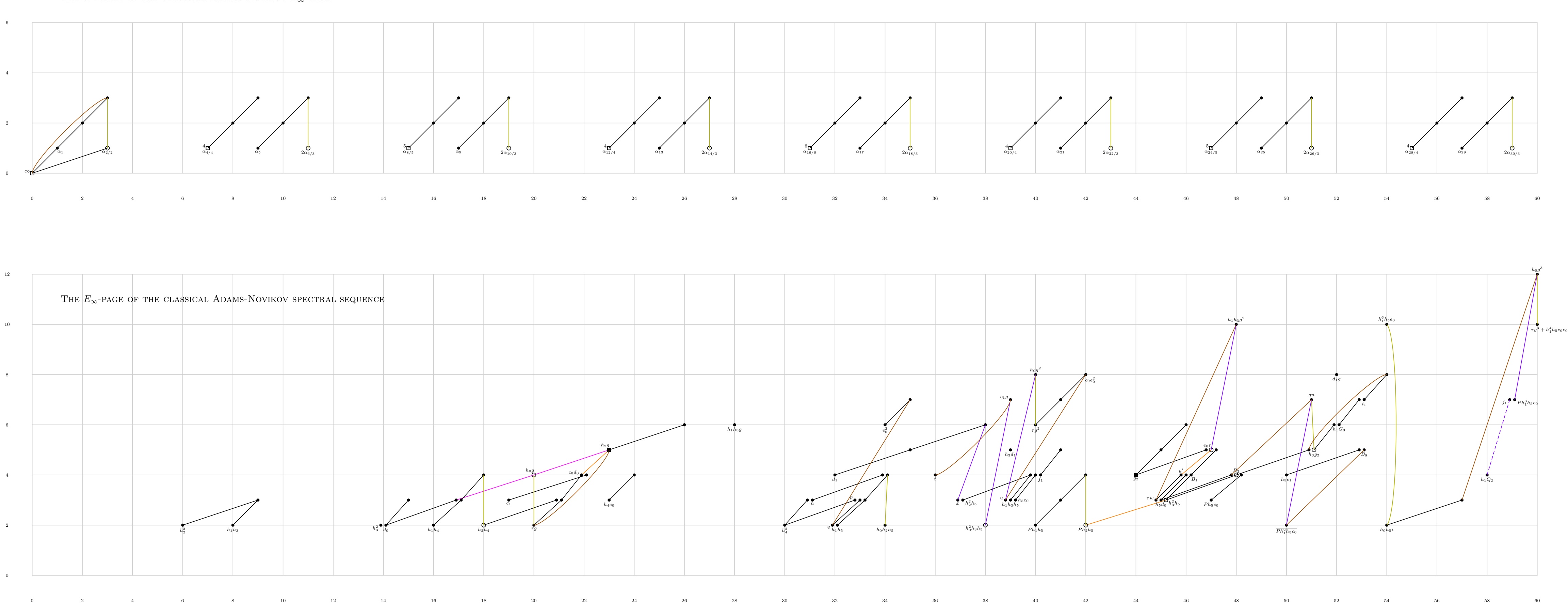

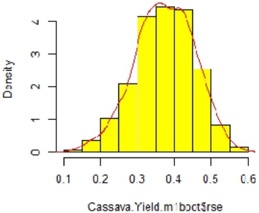

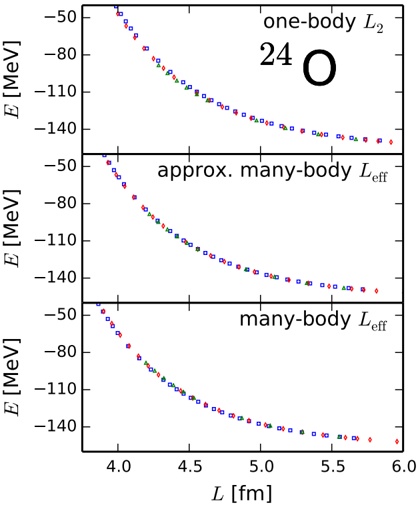

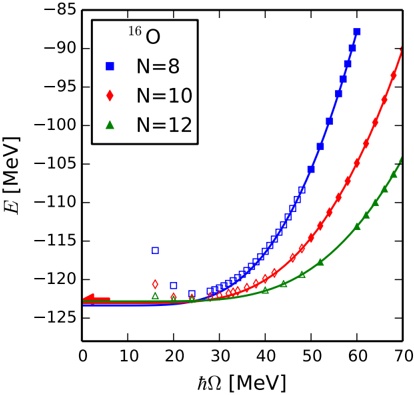

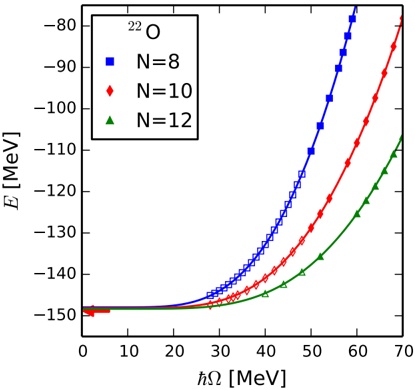

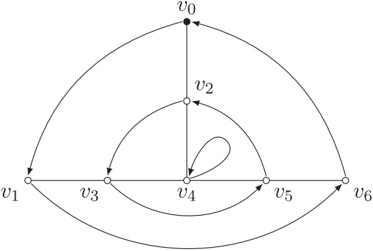

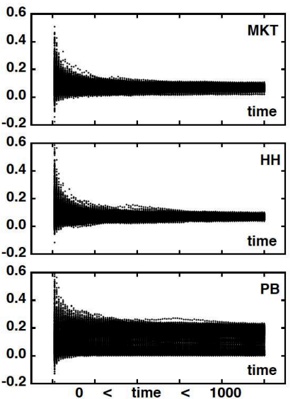

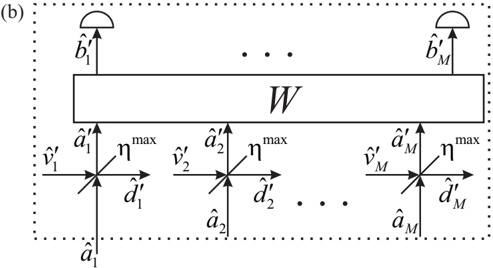

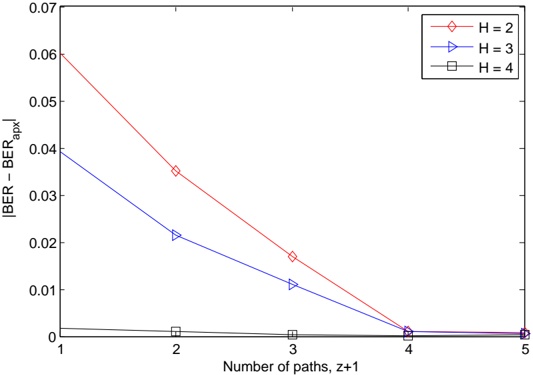

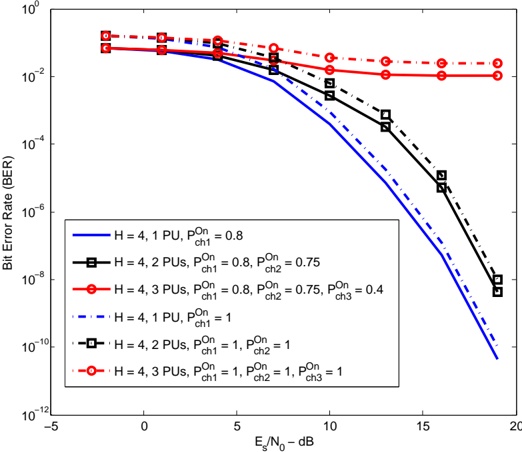

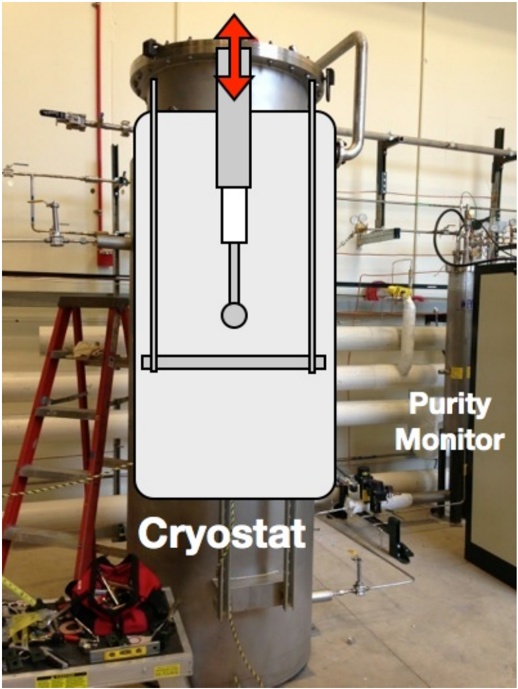

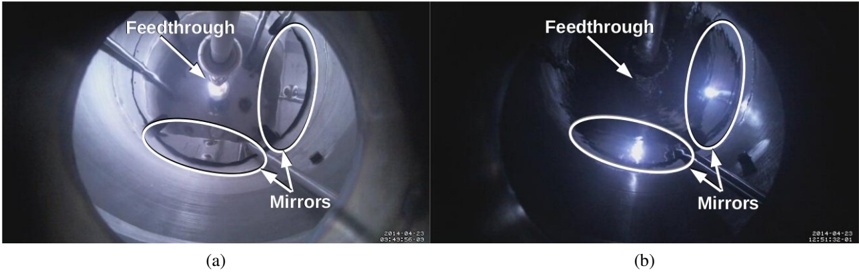

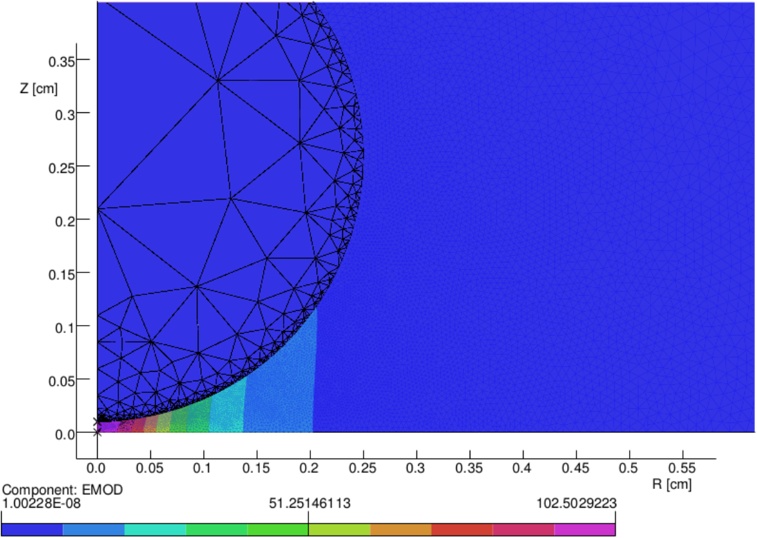

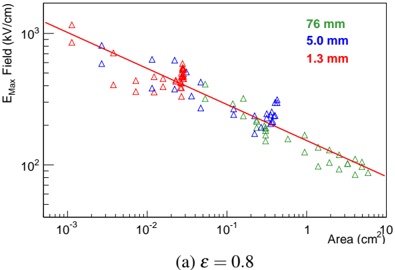

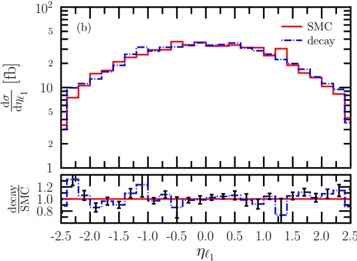

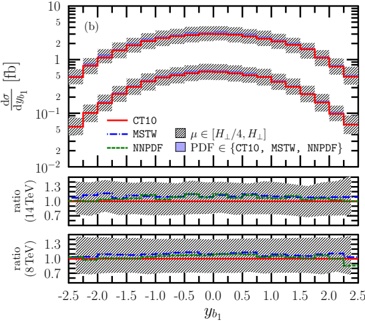

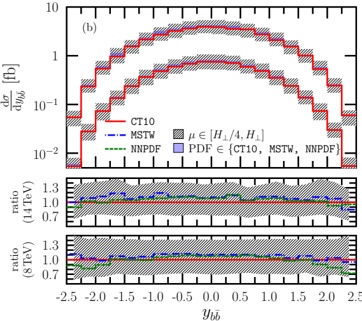

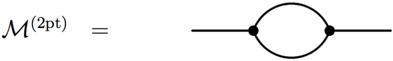

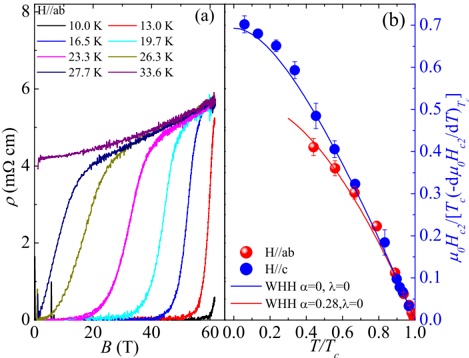

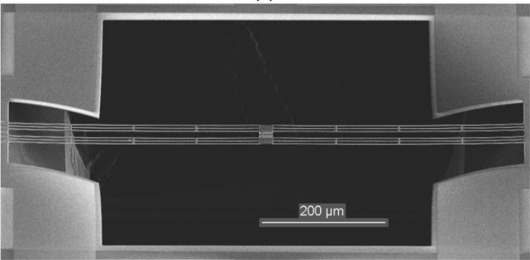

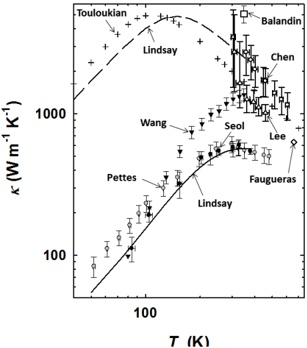

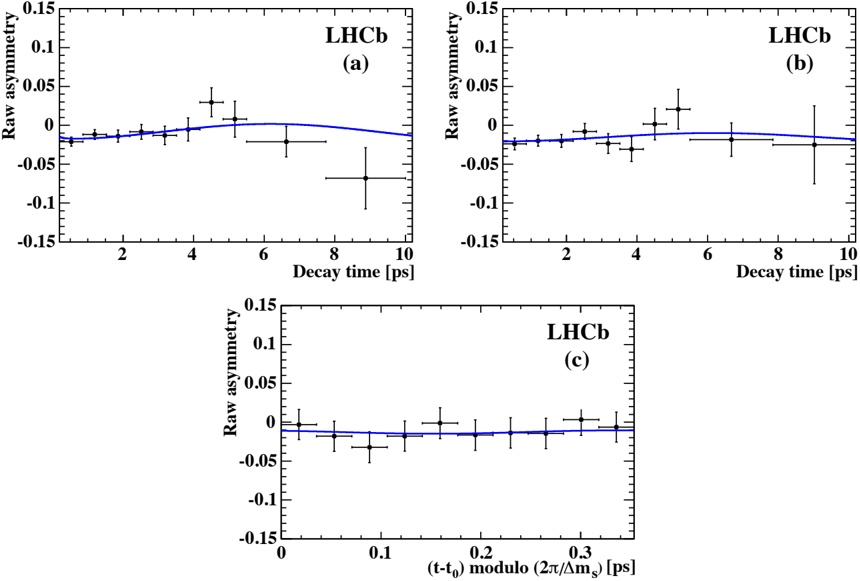

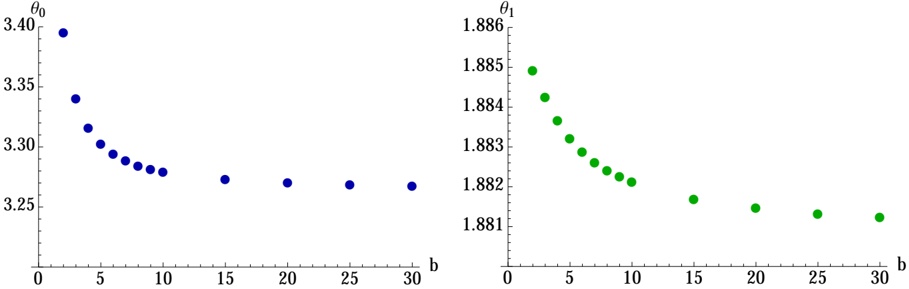

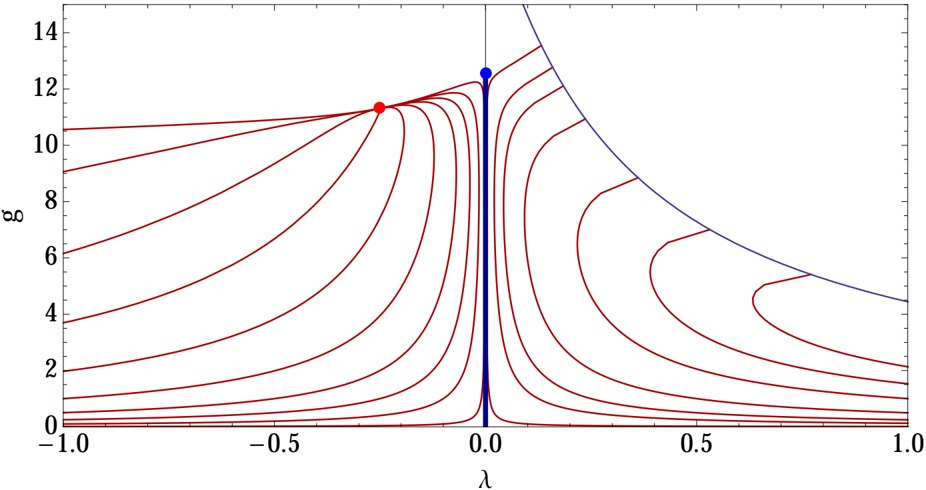

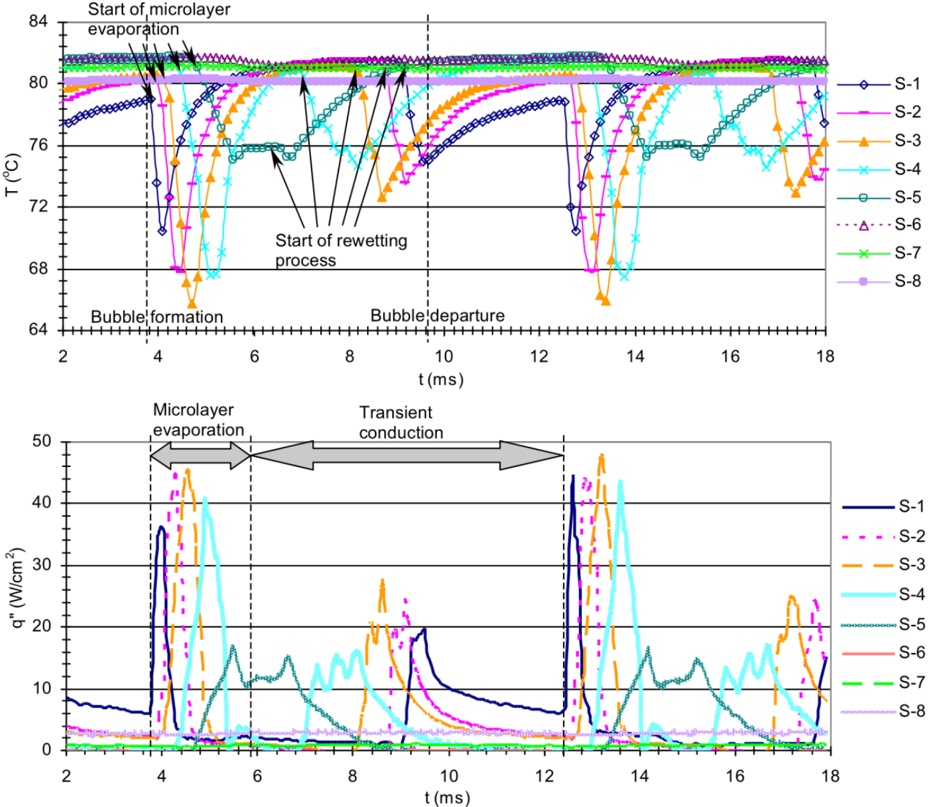

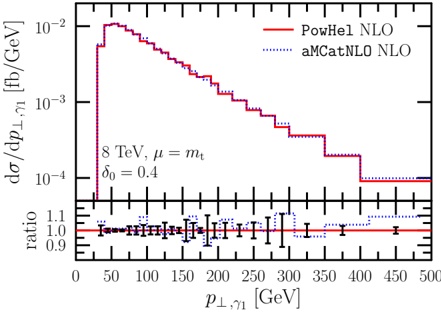

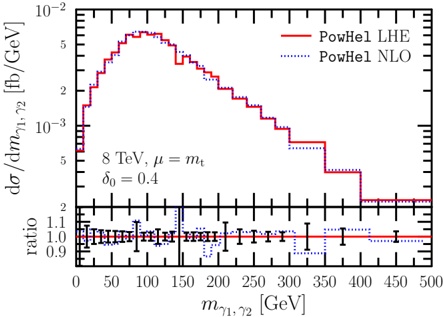

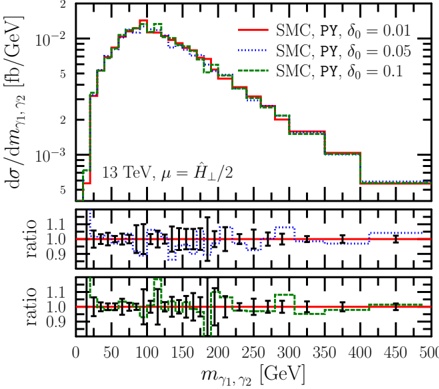

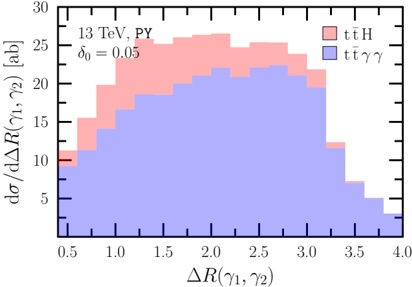

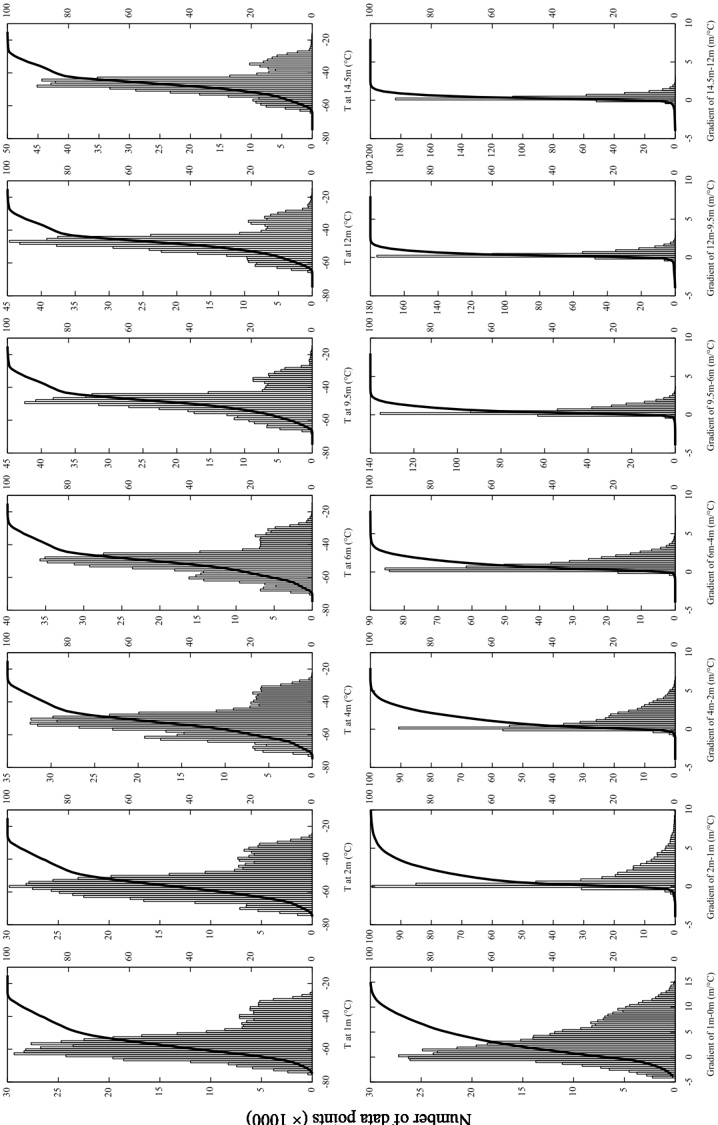

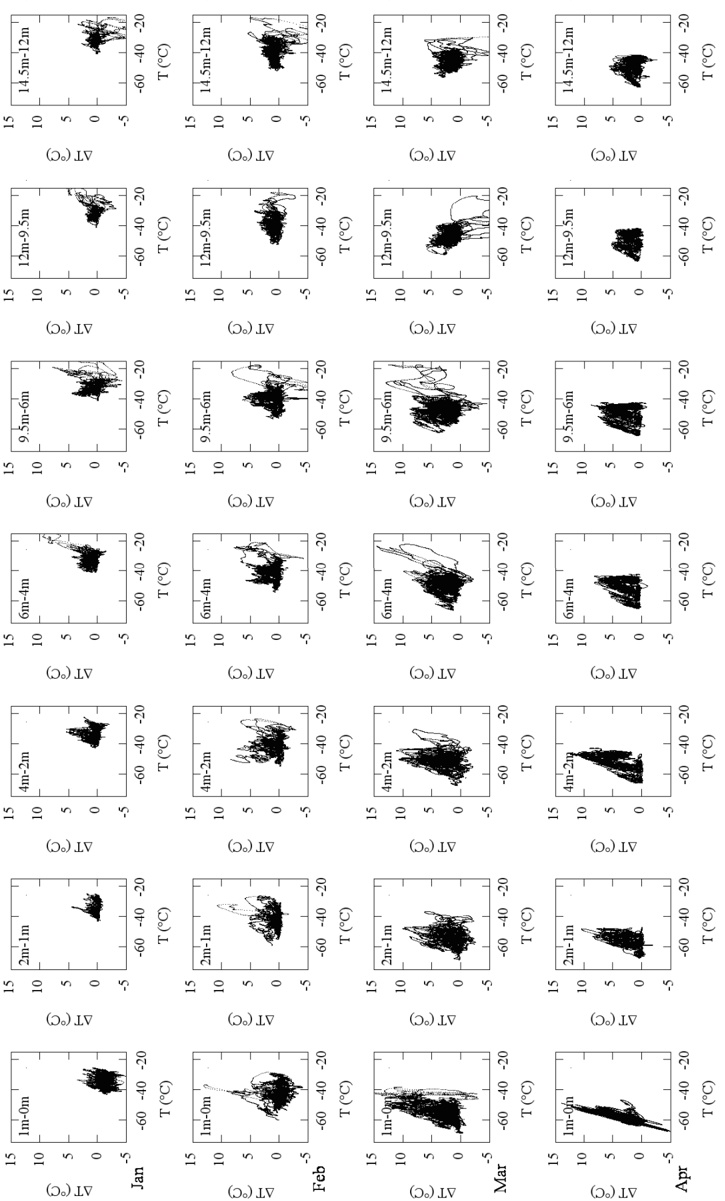

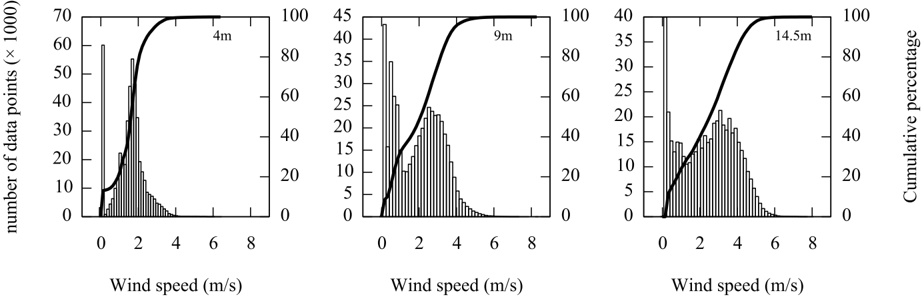

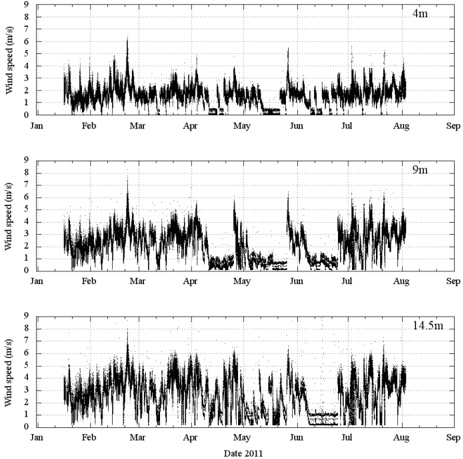

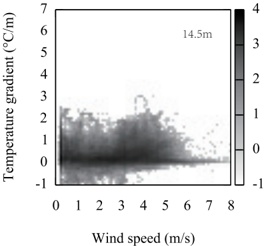

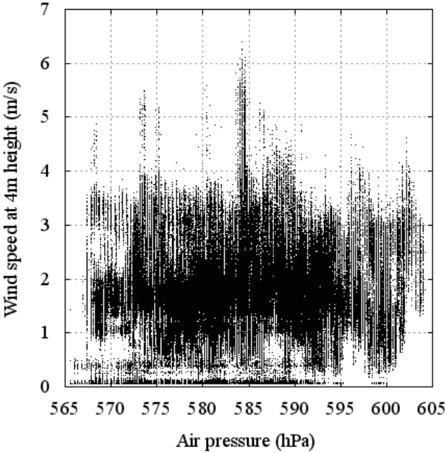

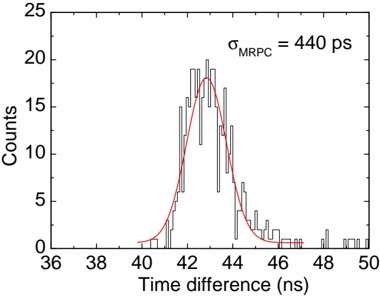

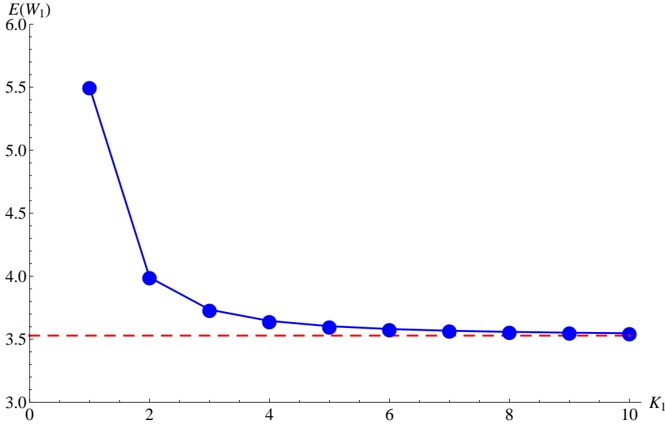

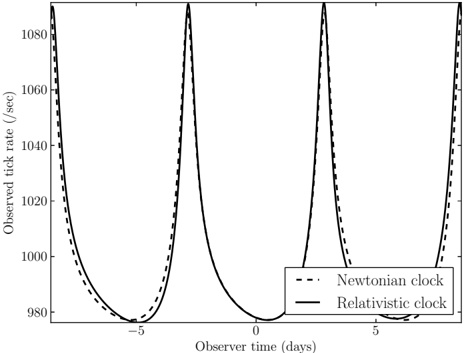

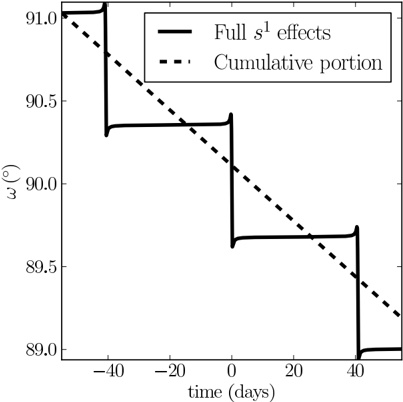

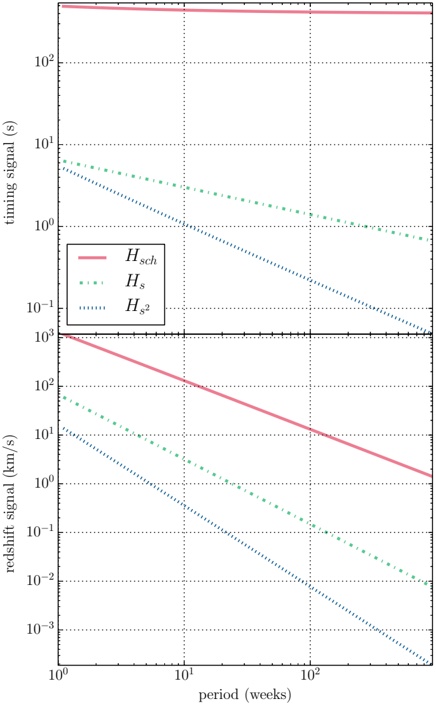

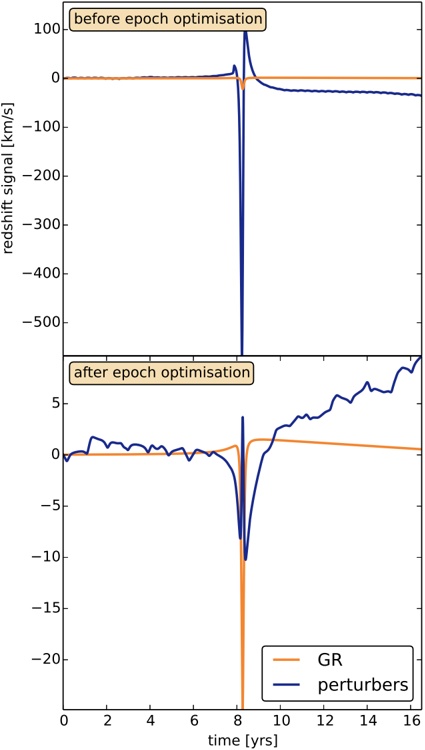

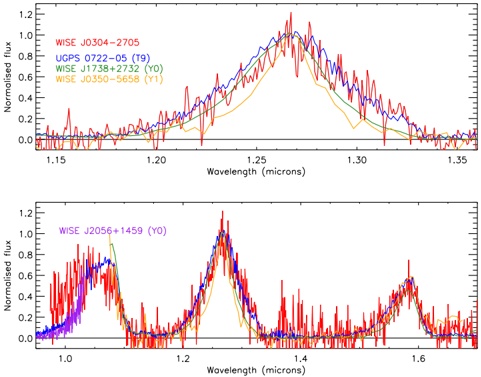

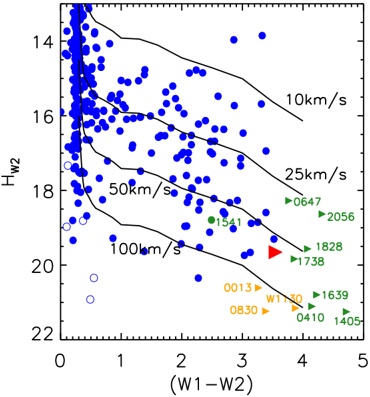

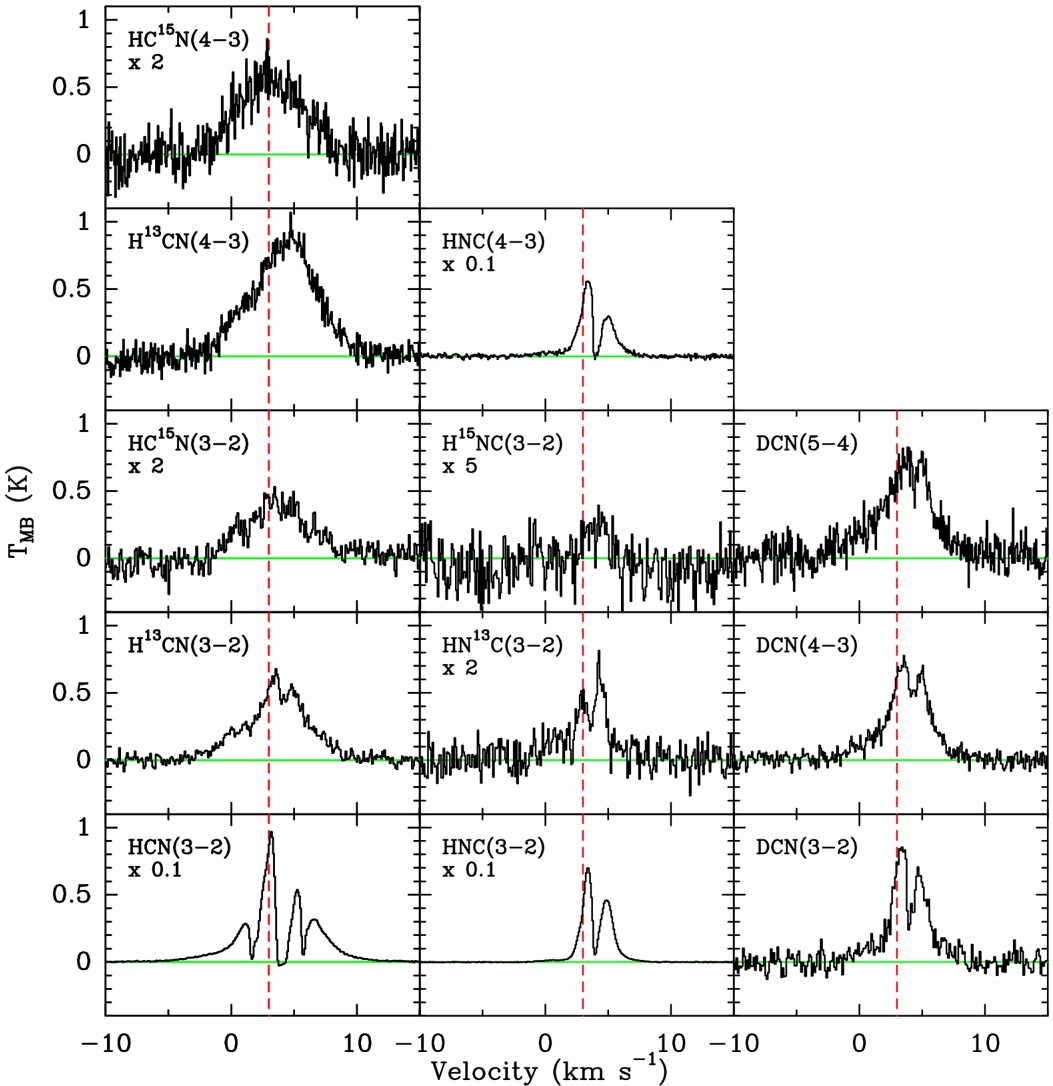

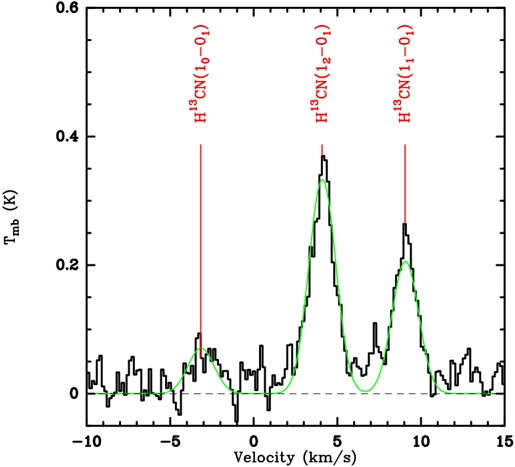

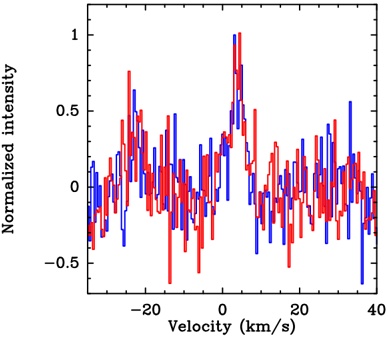

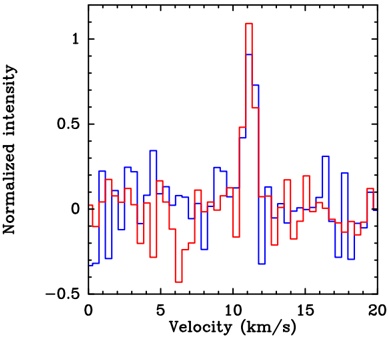

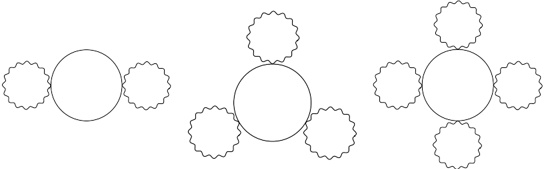

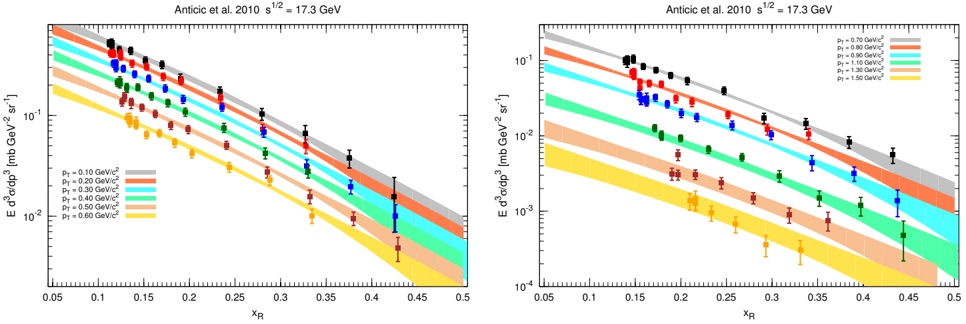

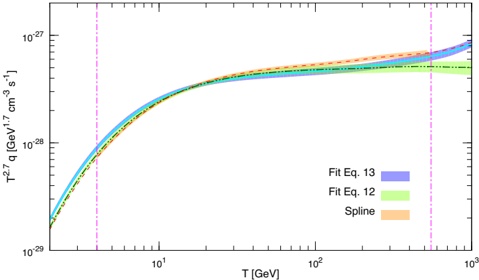

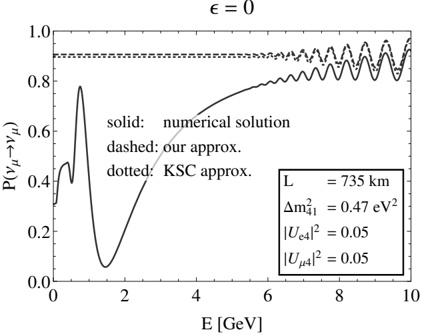

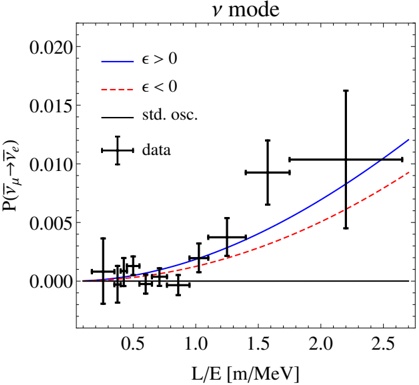

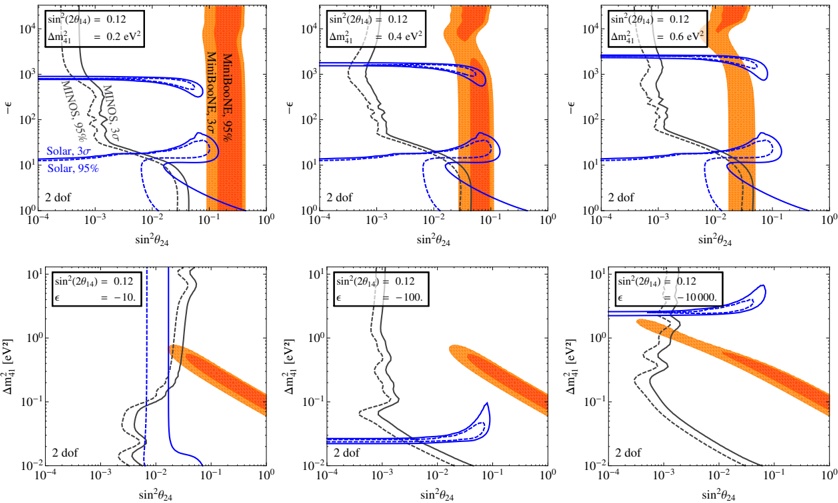

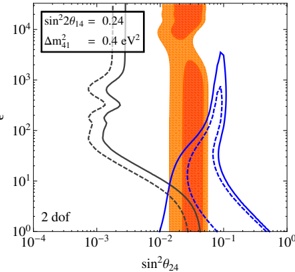

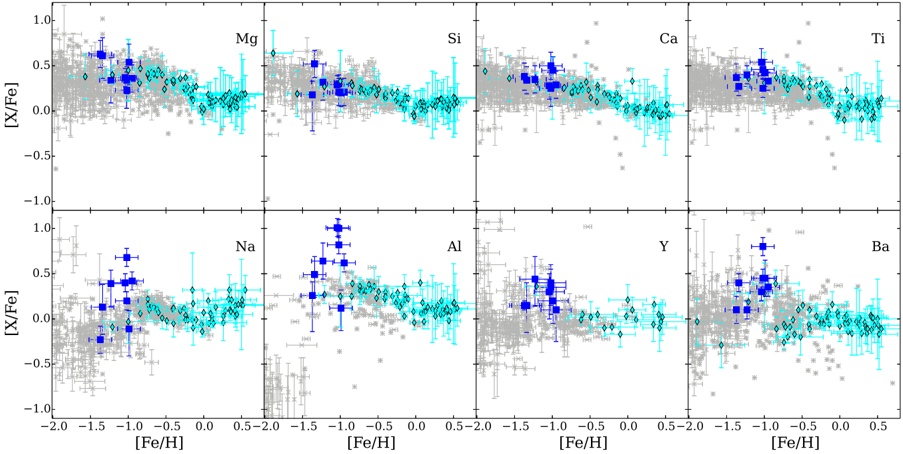

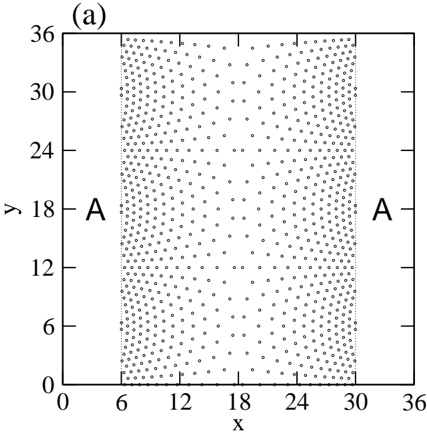

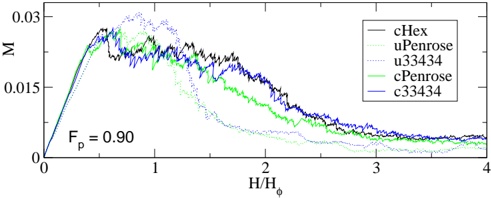

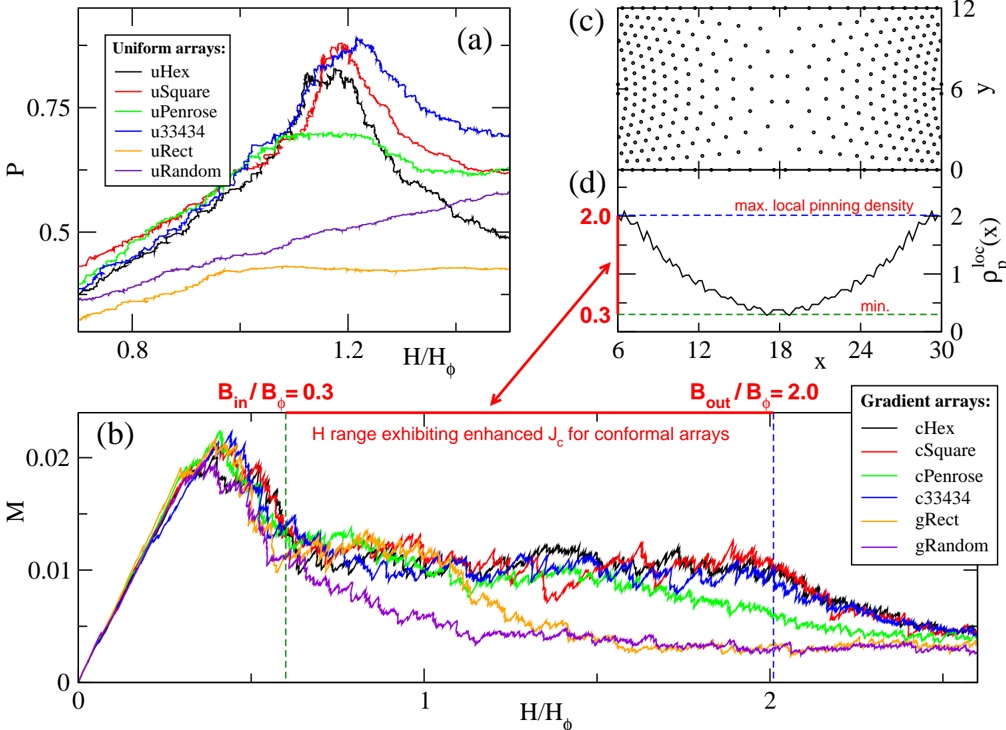

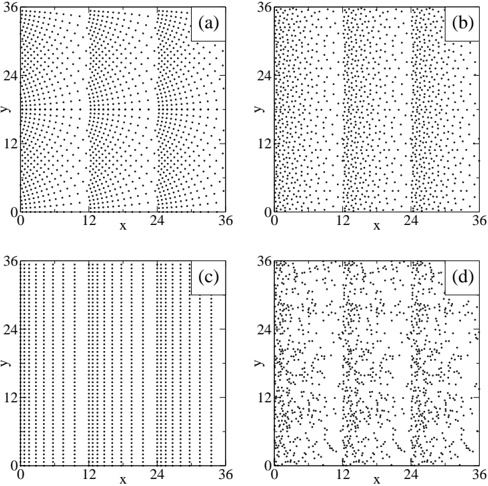

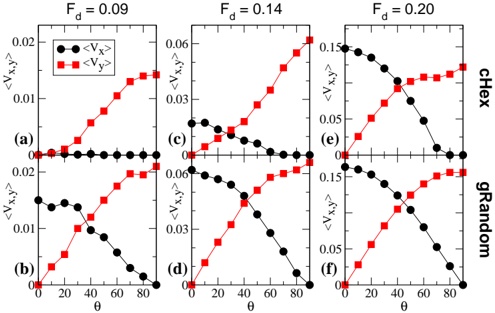

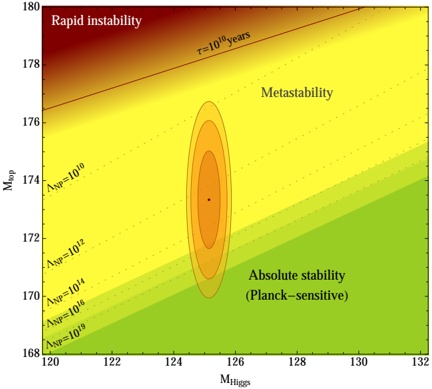

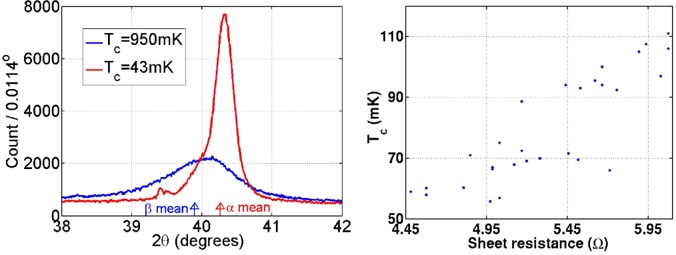

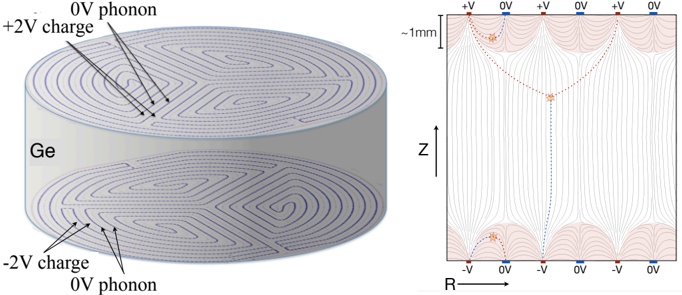

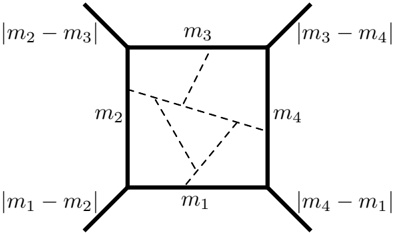

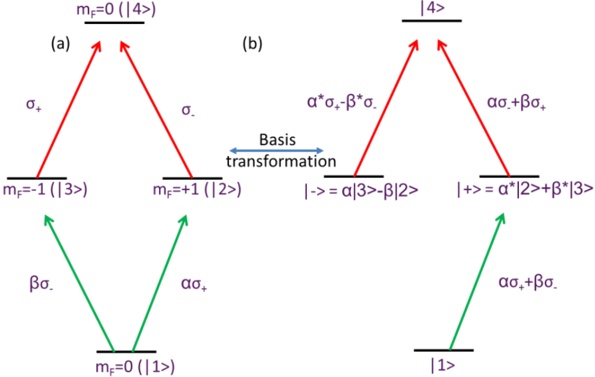

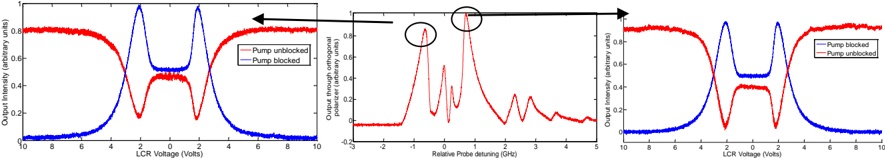

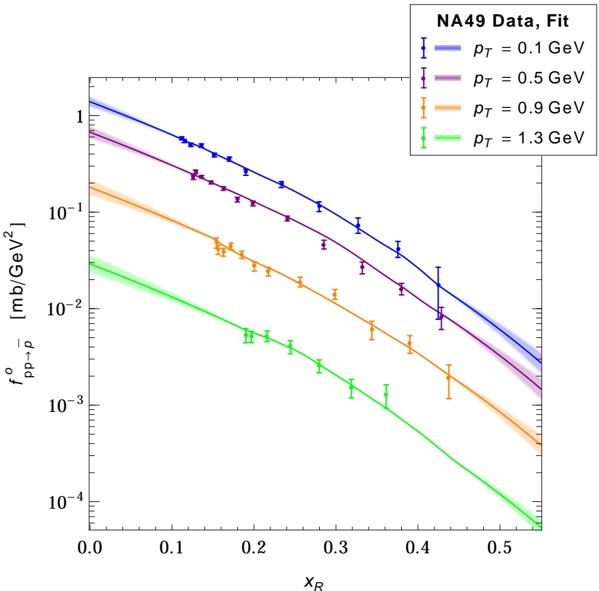

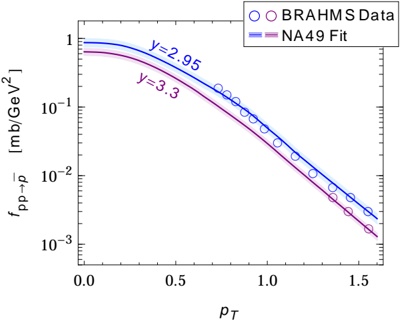

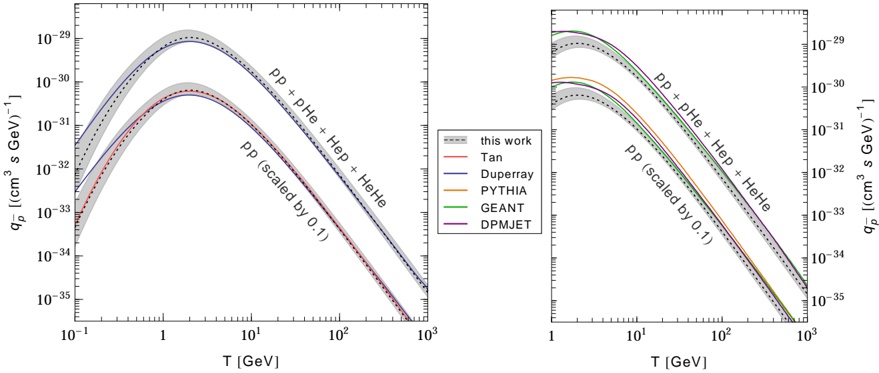

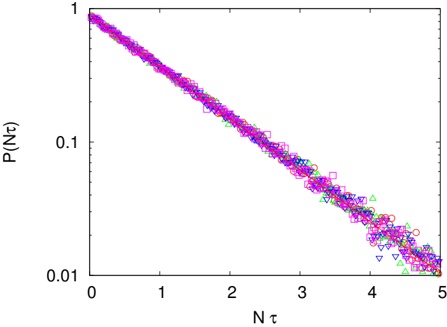

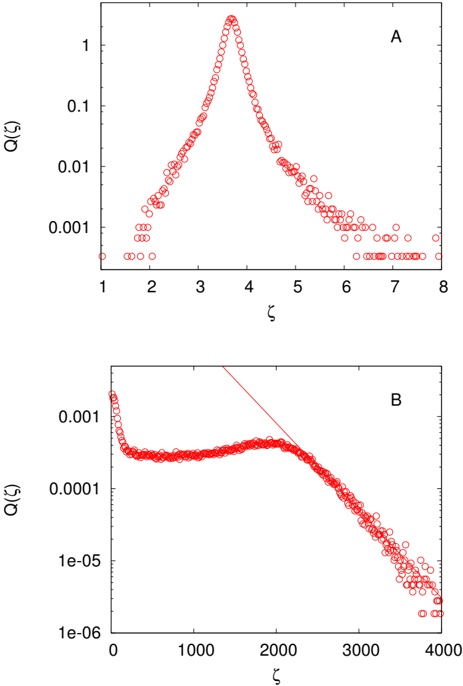

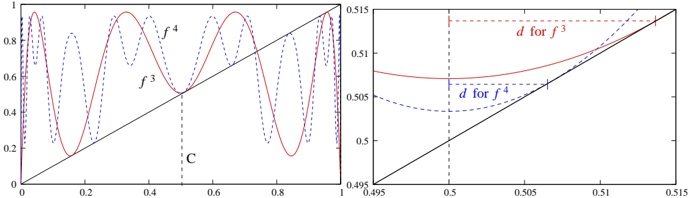

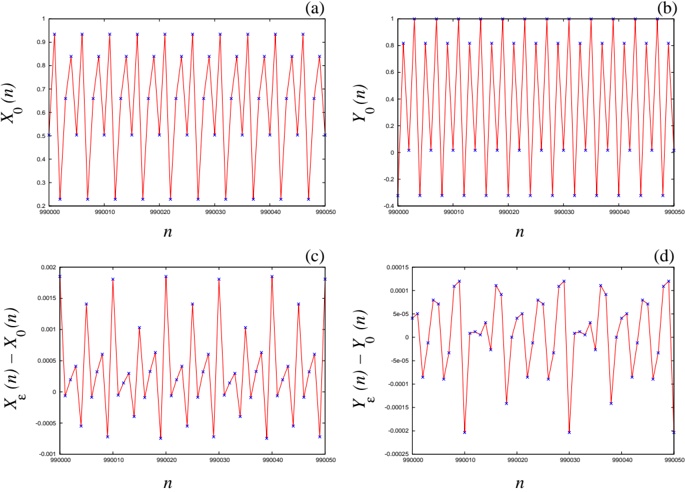

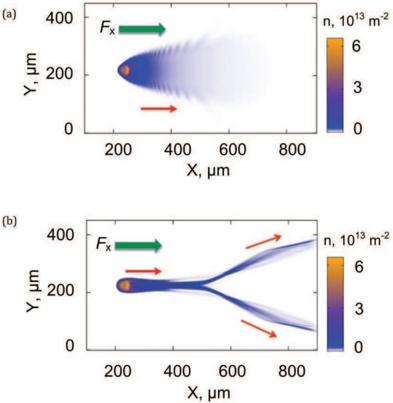

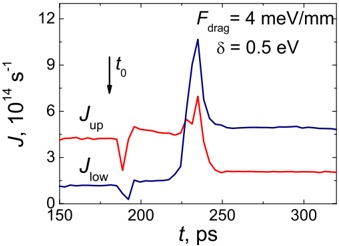

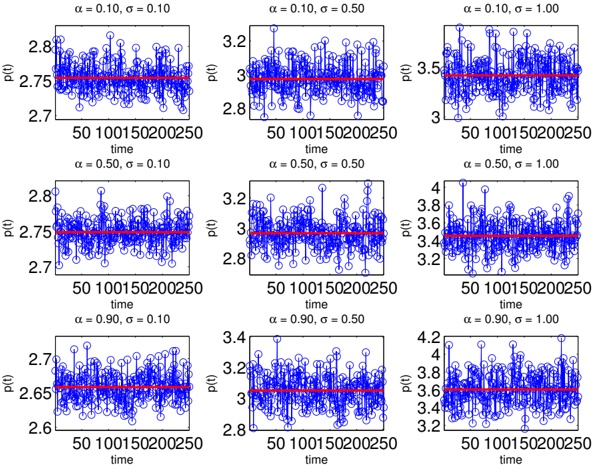

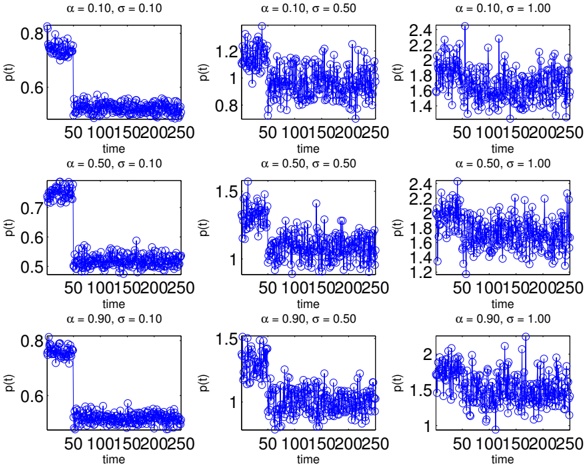

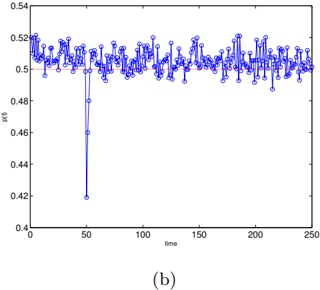

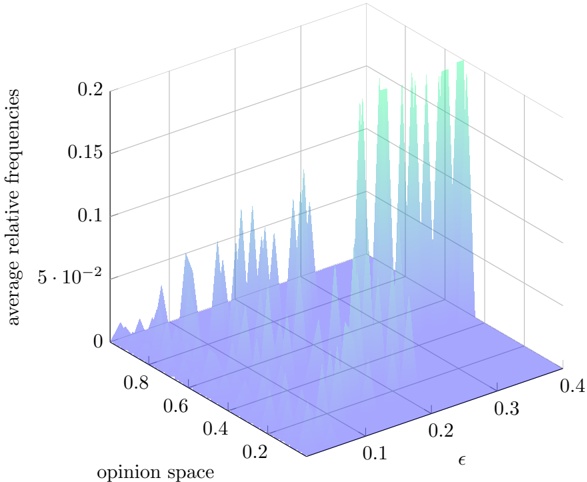

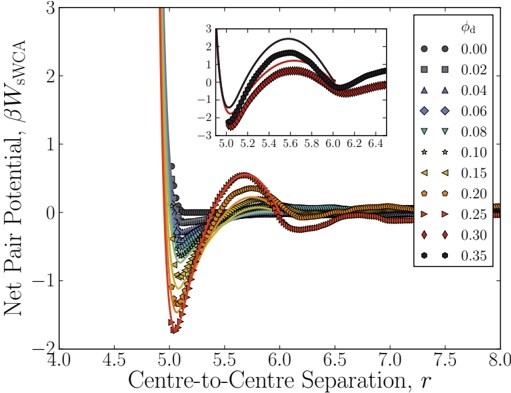

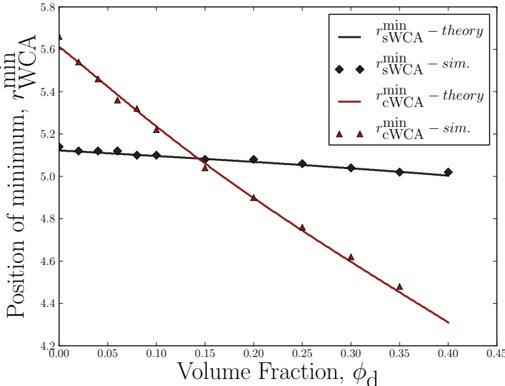

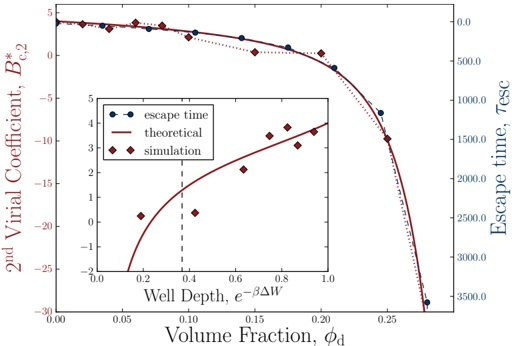

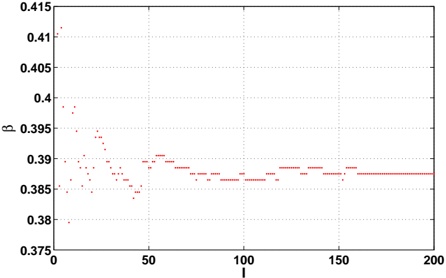

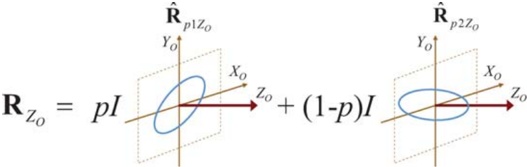

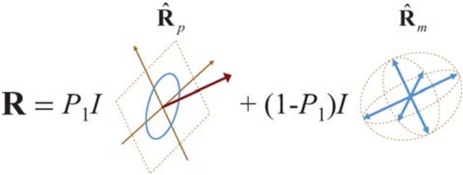

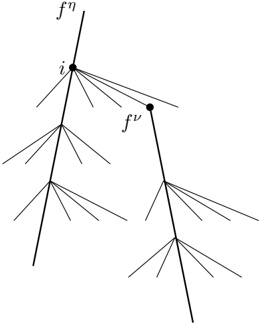

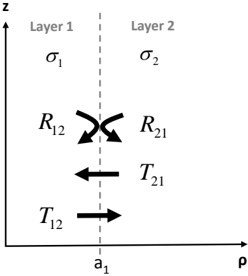

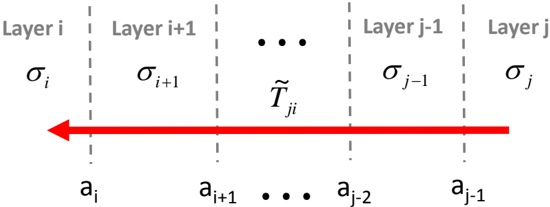

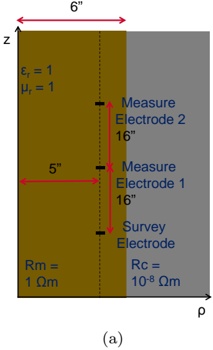

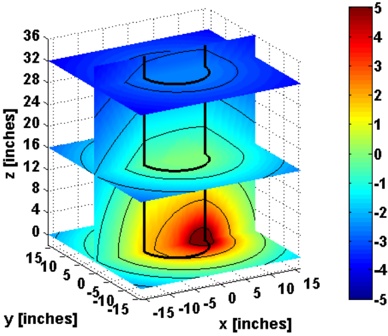

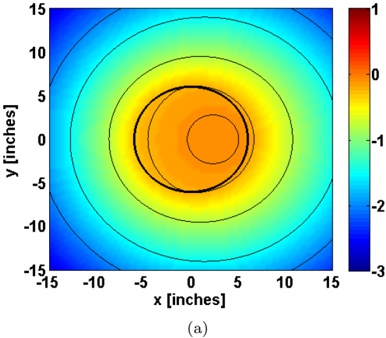

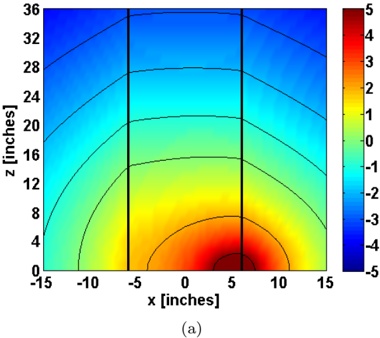

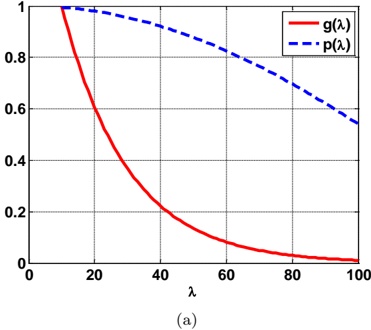

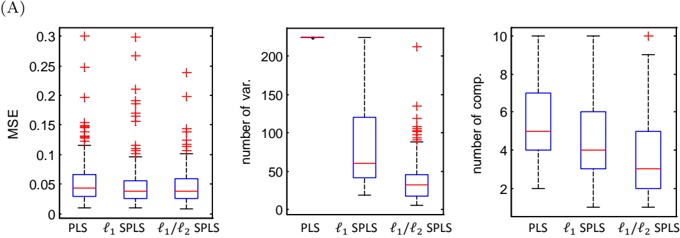

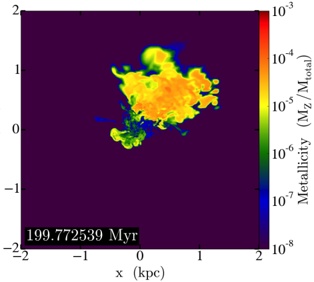

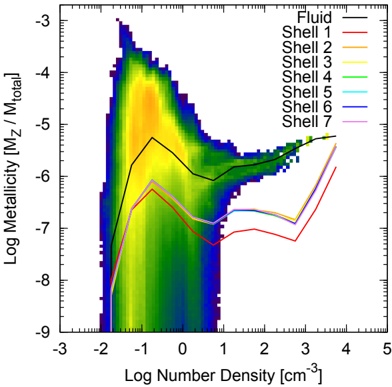

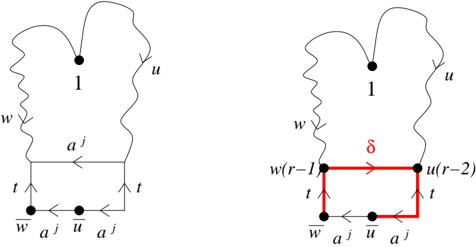

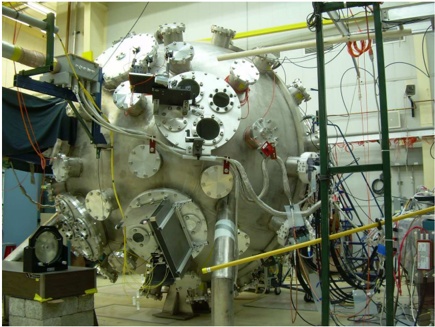

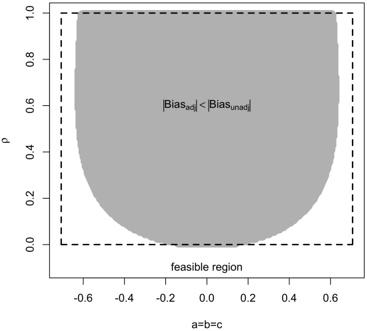

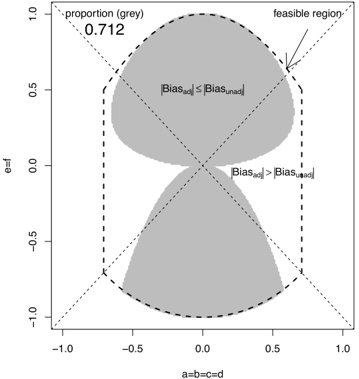

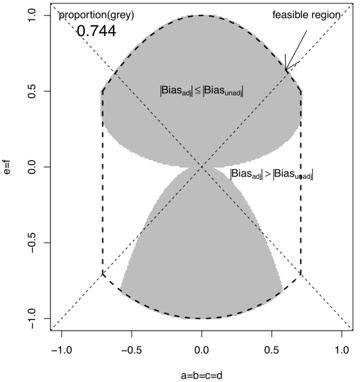

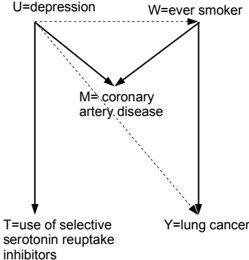

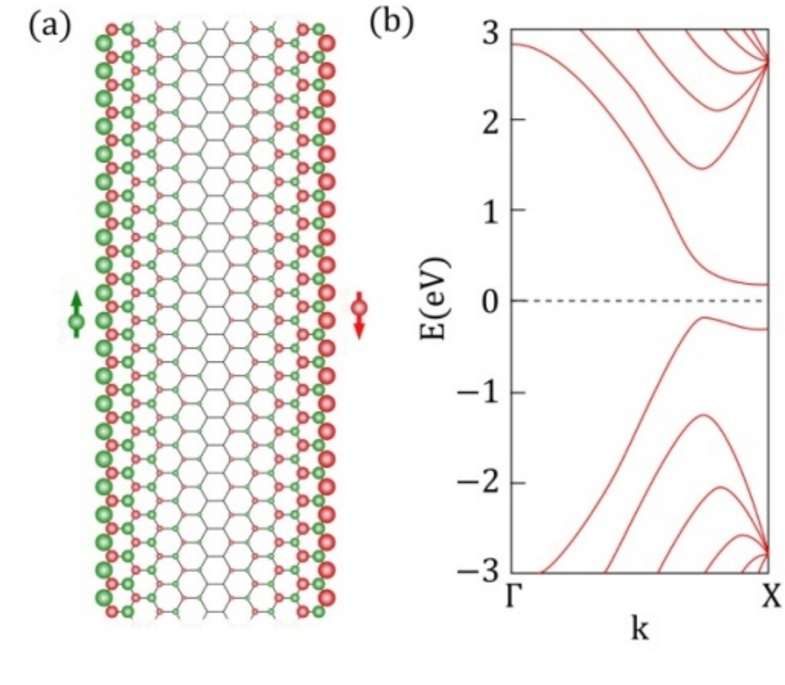

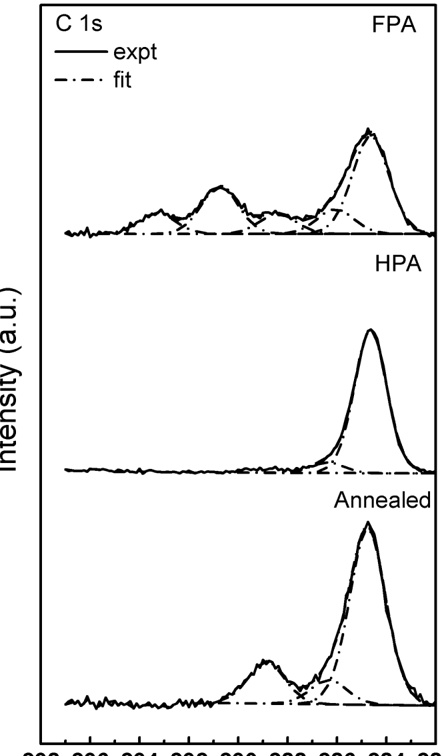

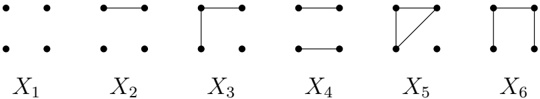

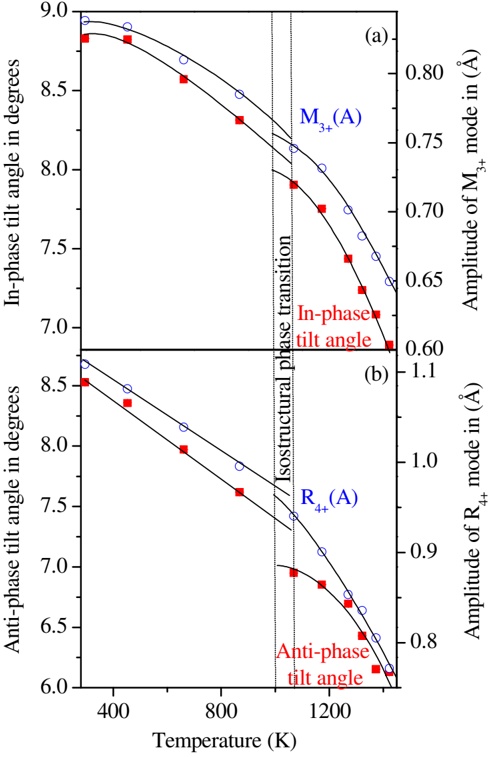

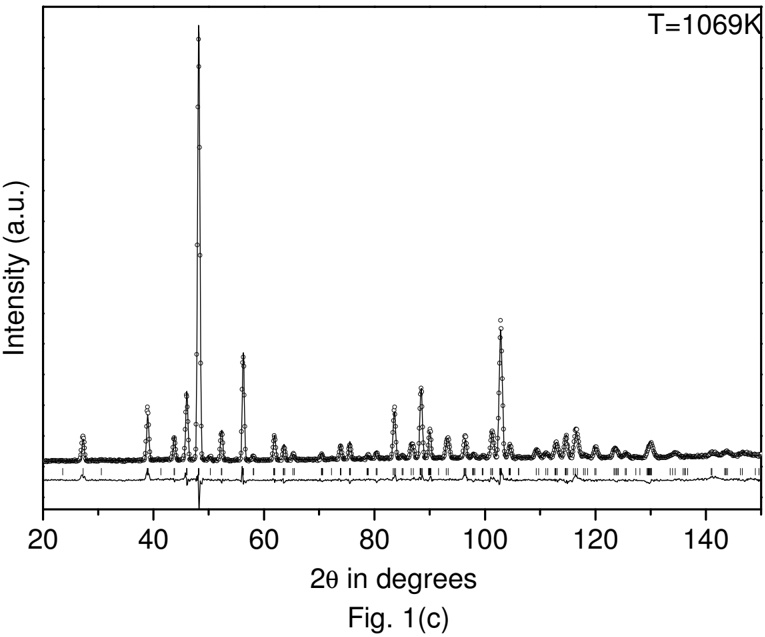

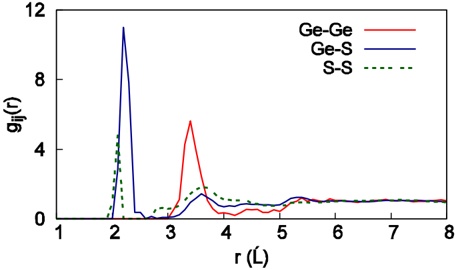

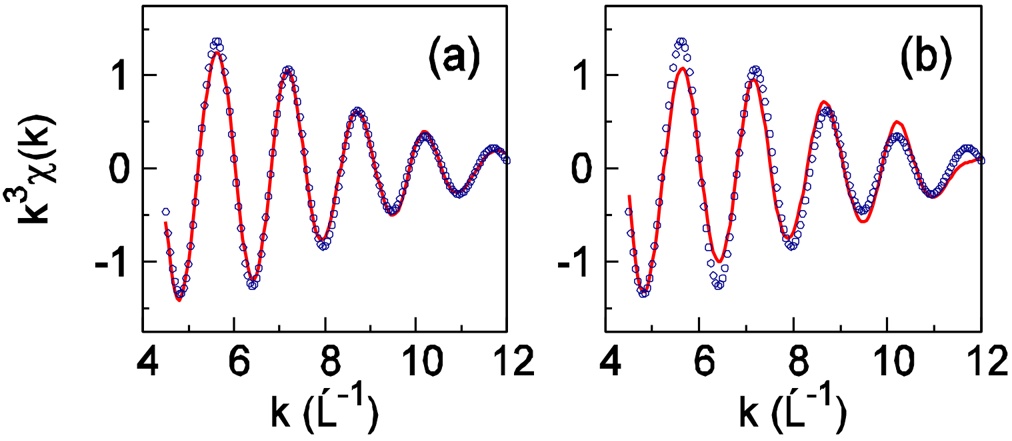

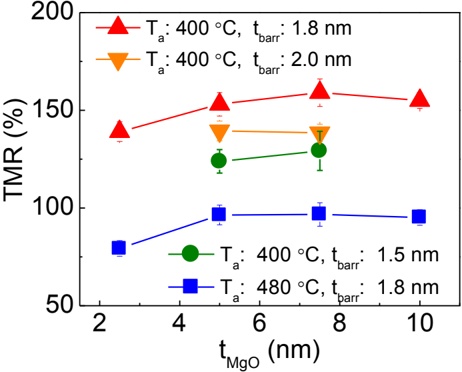

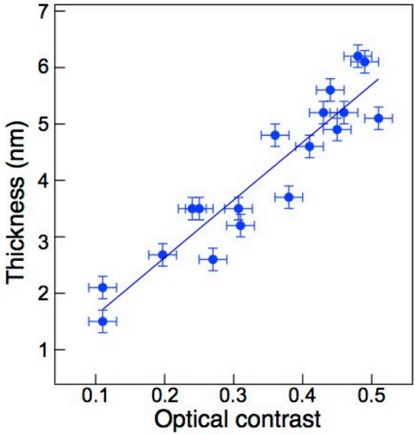

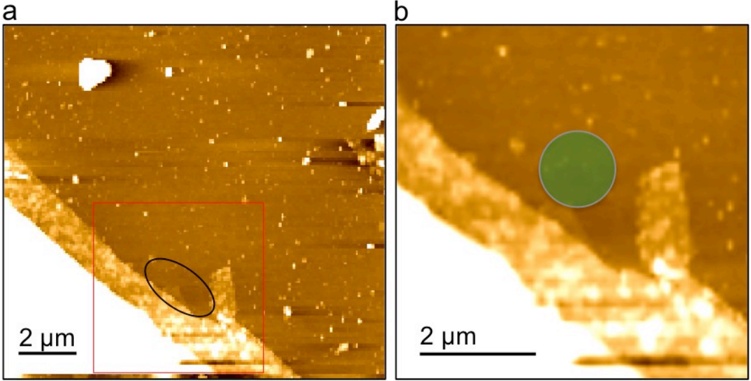

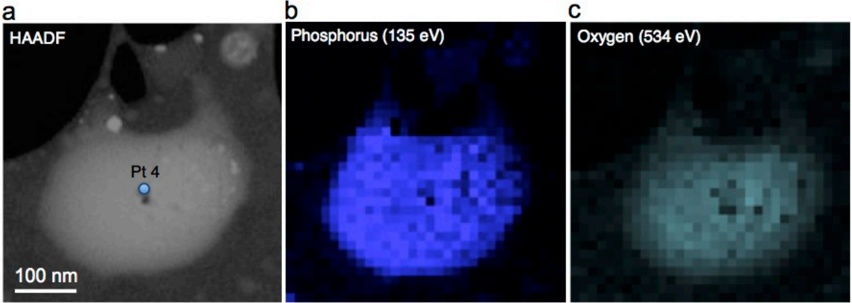

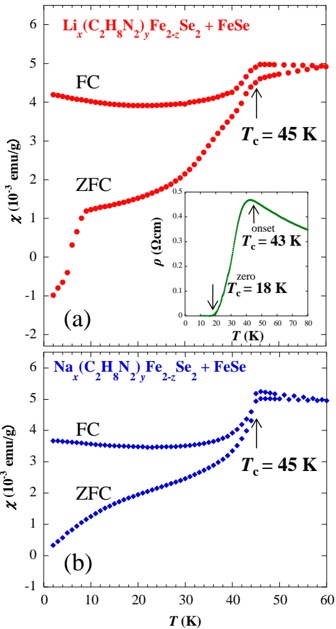

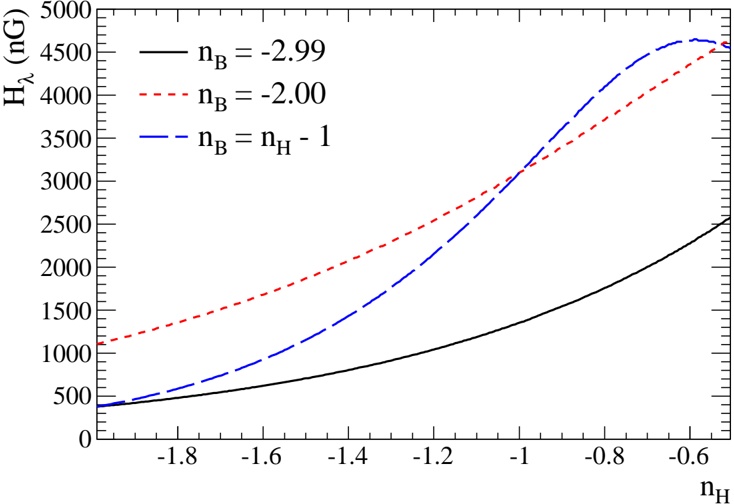

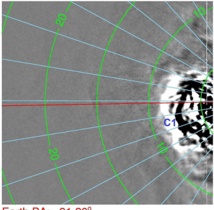

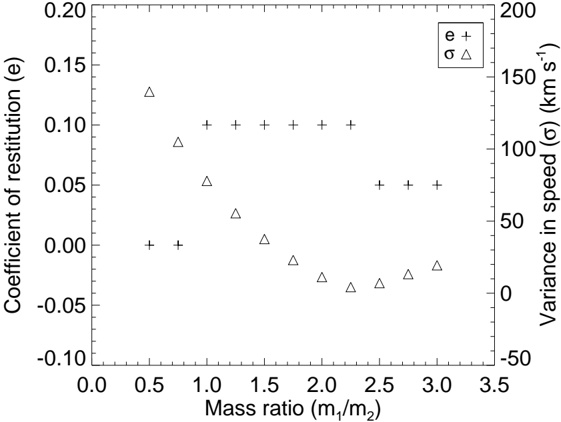

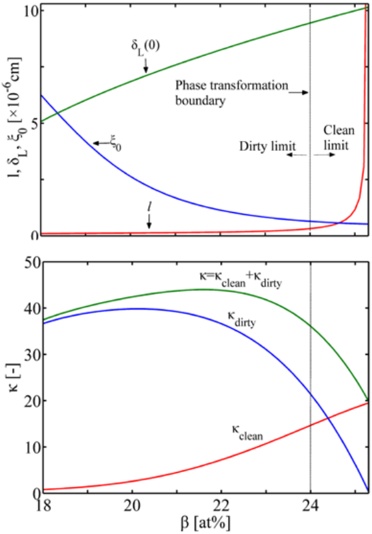

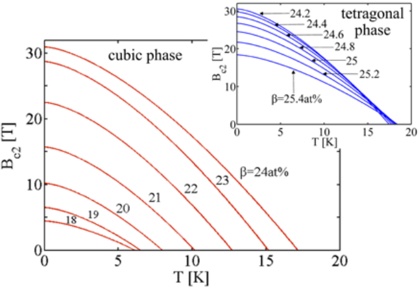

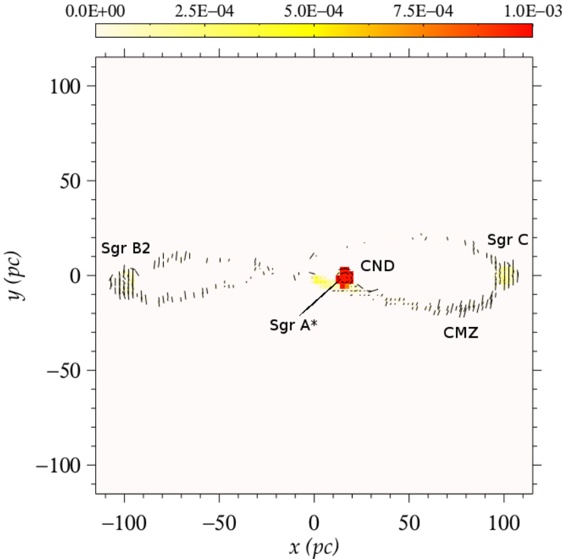

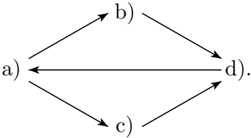

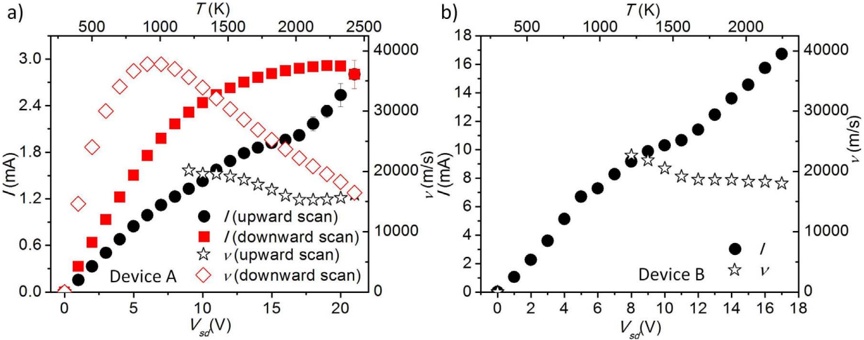

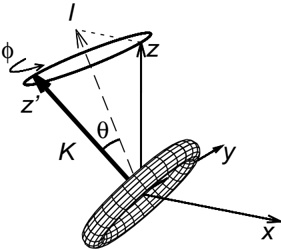

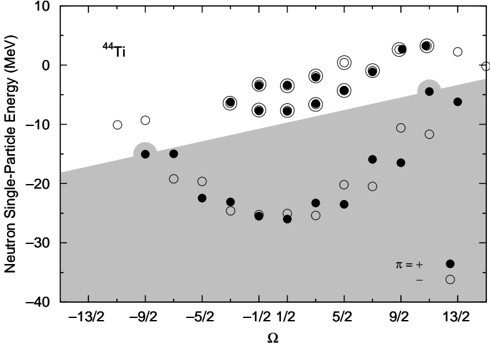

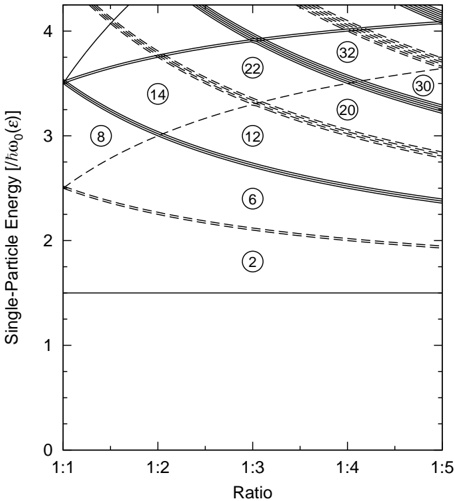

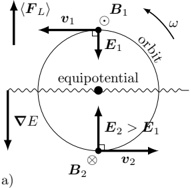

Figure 2 shows a large offset between Phot03 and EHK12 in both V and B as well as a large amount of scatter at all magnitudes and stellar positions. 〈 V EHK12 -V Phot03 〉 and 〈 B EHK12 -B Phot03 〉 are 0.115 ± 0.001 and 0.073 ± 0.002, respectively. Also, V EHK12 -V Phot03 has a rms error of 0.127 and B EHK12 -B Phot03 has an rms error of 0.0935, almost triple the rms errors found with the Y13 photometry comparison.

## 2.3. Photometry Summary

We currently use only the V I photometry from Y13 for our RV survey and in this paper. We made this decision due to the limited radial extent of the previous BV photometry sets and the large offsets and lack of precision in EHK12. Y13 V I photometry provides photometry for 98% of our RV survey and covers the entire radial extent of our survey.

As seen clearly in Figure 1 our photometry comparisons have revealed spatial trends in V Y13 -V Phot03 and I Y13 -I Phot03 with distance from the center of the cluster. Clem & Landolt (2013) note a similar trend in the difference between their calibrated magnitudes and those of Landolt standards which vary as a function of x and y

Figure 2. Comparison of the photometry for overlapping sources between Everett, Howell & Kinemuchi (2012) and Phot03. The top row of figures shows V EHK12 minus V Phot03 as a function of V Phot03 (left) and as a function of radial distance from the center of the cluster (right). The bottom row shows the same comparisons for B EHK12 and B Phot03 .

position relative to the center of the two different detectors used in their study. They attribute this systematic trend to the failure of the flat fields to completely correct for large-scale illumination patterns in the detector systems. This detector-independent flat fielding effect may be the cause of the trends seen in the Y13 data as well. Regardless, the typical magnitude and color errors are less than 0.05 and will not affect any of the kinematic results discussed in the rest of this paper.

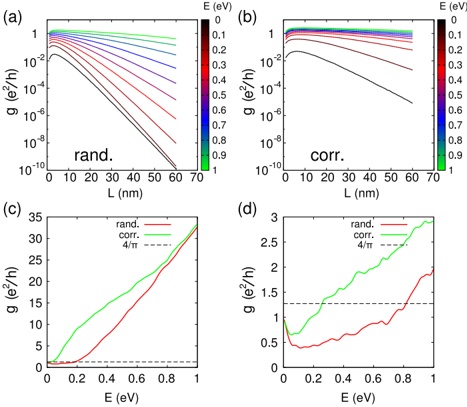

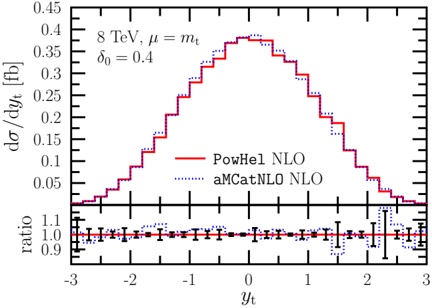

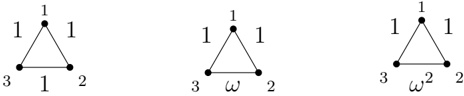

P µ , are calculated with local-sample techniques (Kozhurina-Platais et al. 1995) which utilize separate two-dimensional Gaussian frequency distributions of the field and the cluster for a limited sample of stars. The limited samples are chosen to contain stars with similar magnitudes and distance from the cluster center as the specific star being analyzed.

Finally, based on Y13 V I photometry of stars within 10 ′ of the cluster center that are proper-motion members Platais et al. (2013) find differential reddening in NGC 6819. As Platais et al. (2013) only analyzed the inner part of our total sample region and we expect the specific ∆ E V ( -I ) quantities may need to be revisited based on the radial trend in Y13 discussed above, we do not incorporate these findings in the photometry in Table 2 or the color -magnitude diagram (CMD) presented in this paper. However, the maximum differential reddening found by Platais et al. (2013) was ∆ E V ( -I ) = 0.09 and we expect associated scatter in the CMD.

## 3. PROPER MOTIONS

Platais et al. (2013) presents proper-motion measurements for 15 , 408 stars in the NGC 6819 field with a precision that ranges from ∼ 0.2 mas yr -1 within 10 ′ of the cluster center to 1.1 mas yr -1 outside of 10 . ′ The study uses CCD observations taken with the MegaCam imager at the CFHT as well as 23 scanned photographic plates from four different telescopes, all with different epochs, depth, scales, and fields of view.

The proper-motion membership probabilities,

This survey provides proper-motion information for 78% of the targets in our RV survey of NGC 6819. The large majority of stars missing proper-motion measurements are outside the area covered by the photographic plates. Proper-motion measurements are also missing for stars that fall near the MegaCam interchip gaps, suffer from image confusion on the photographic plates, or have proper-motions exceeding the upper limit imposed by Platais et al. (2013) of 20 mas yr -1 in either the x or y coordinate.

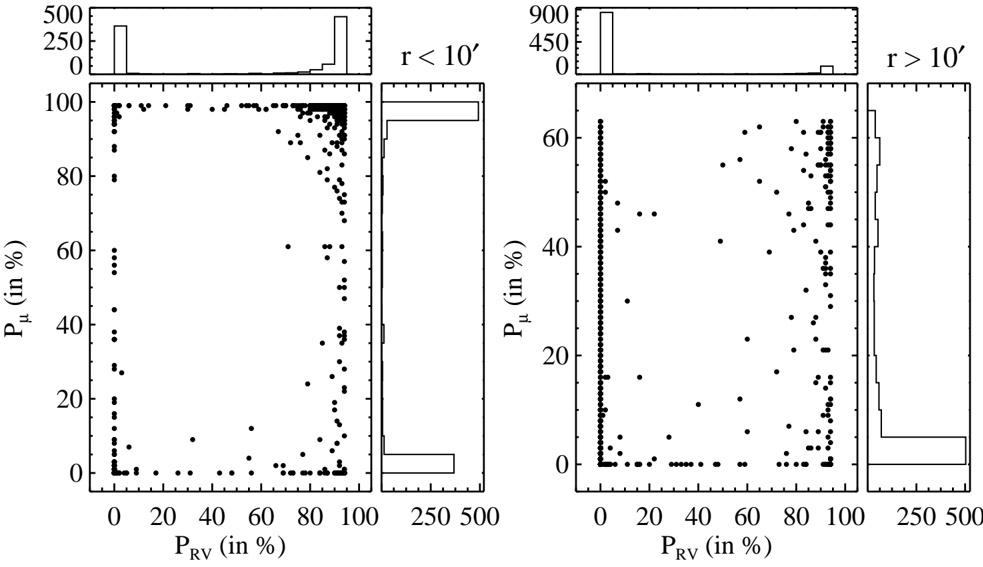

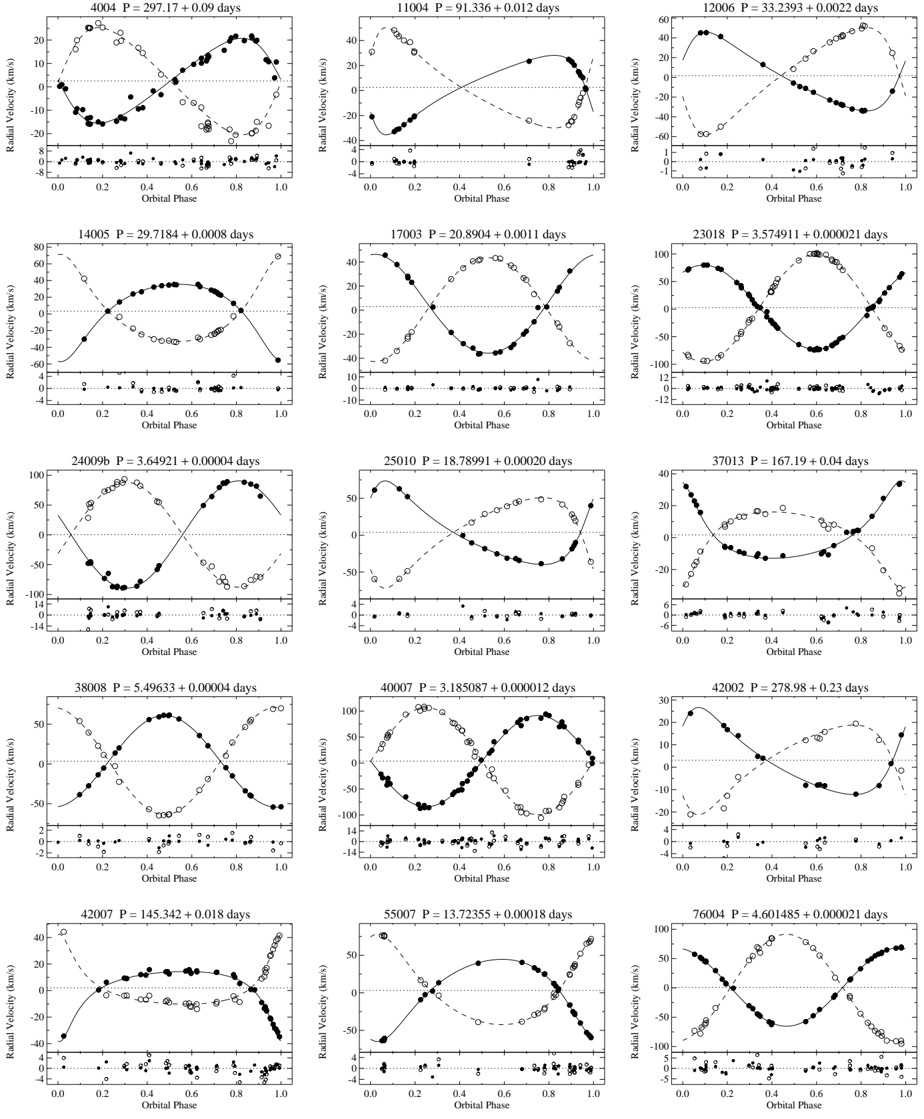

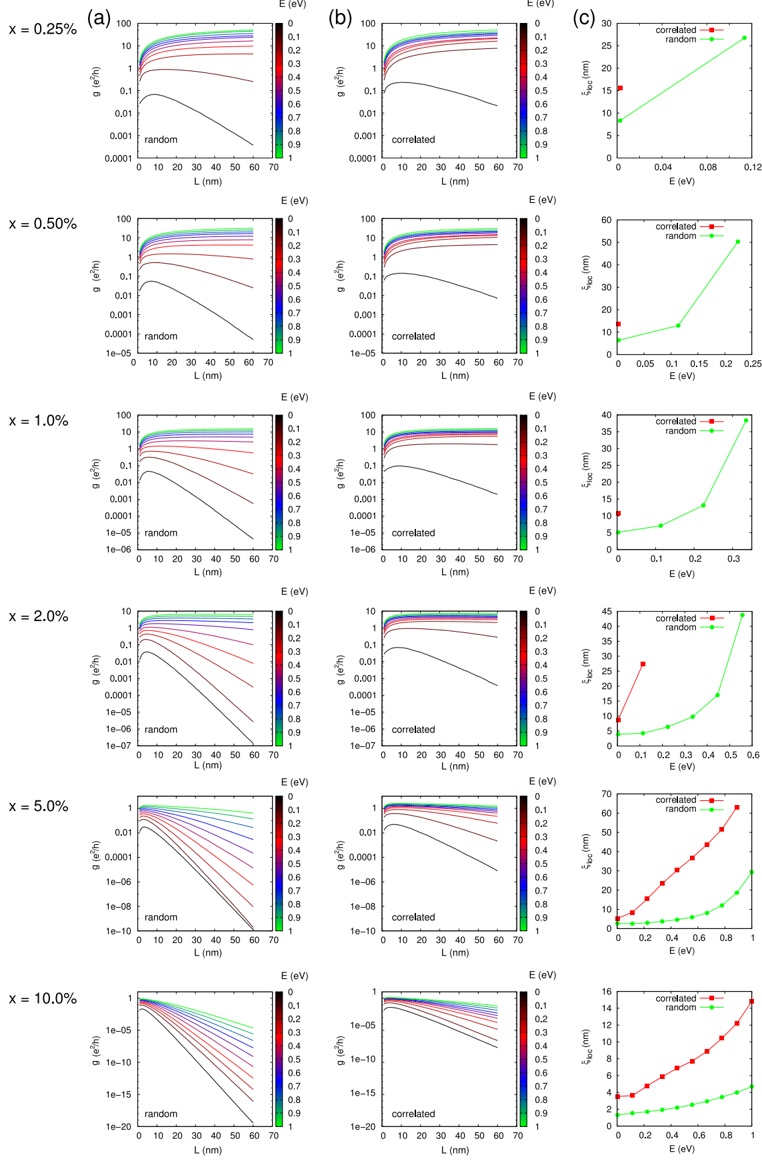

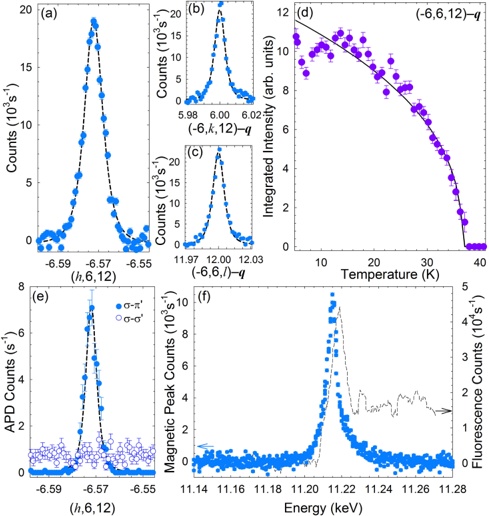

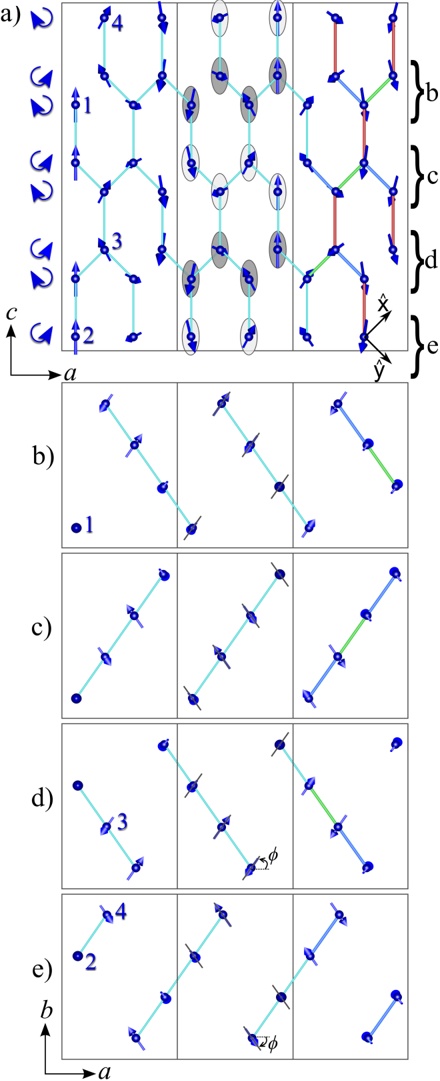

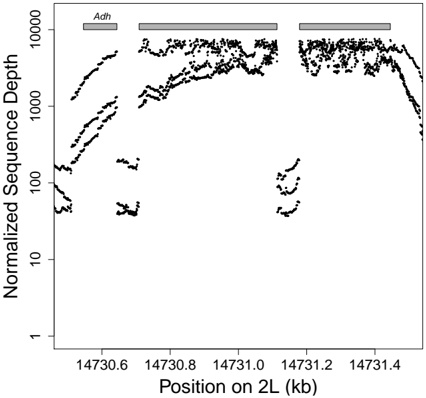

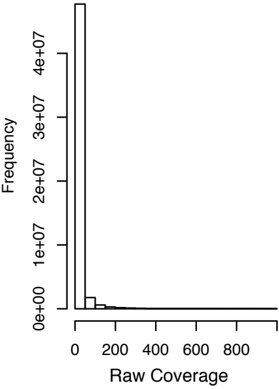

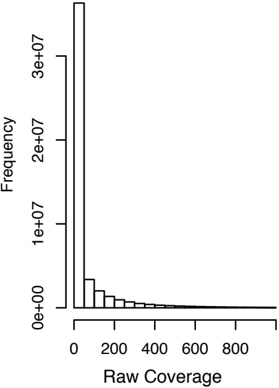

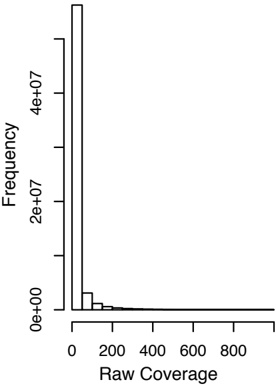

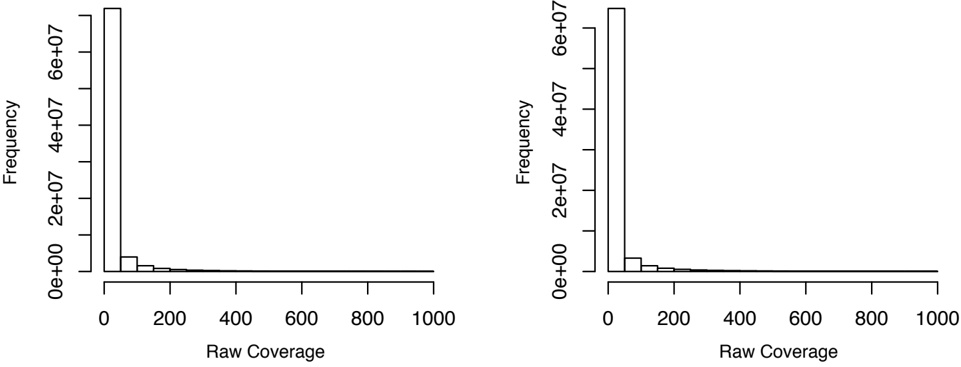

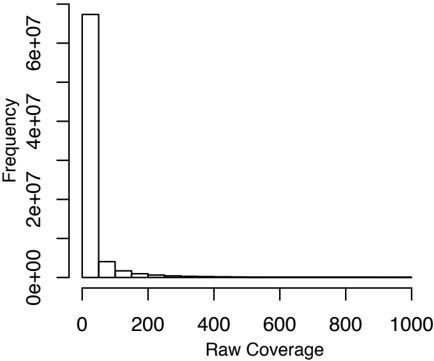

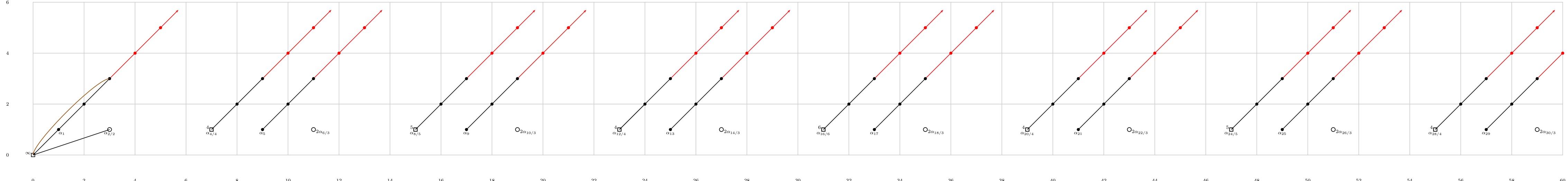

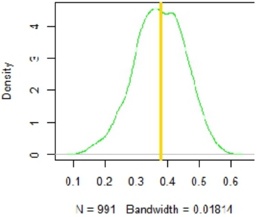

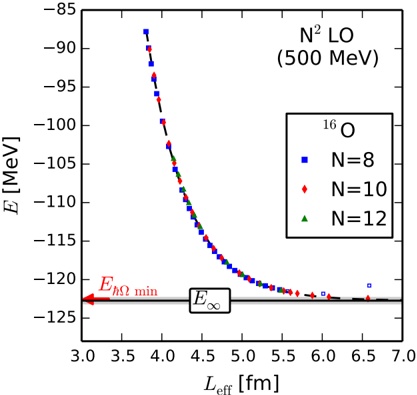

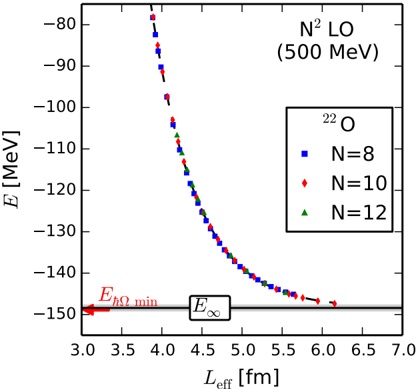

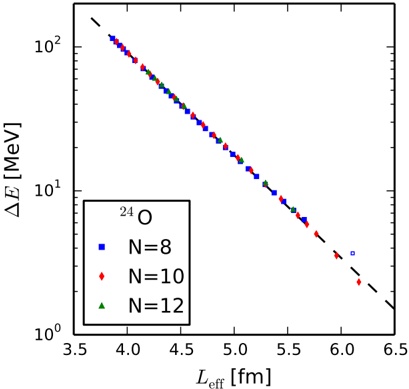

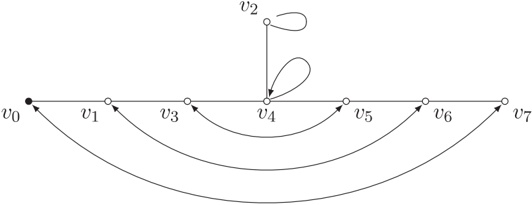

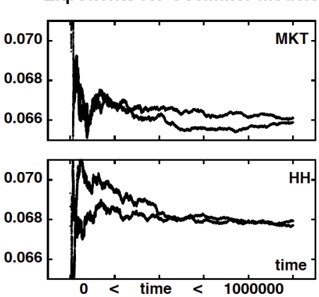

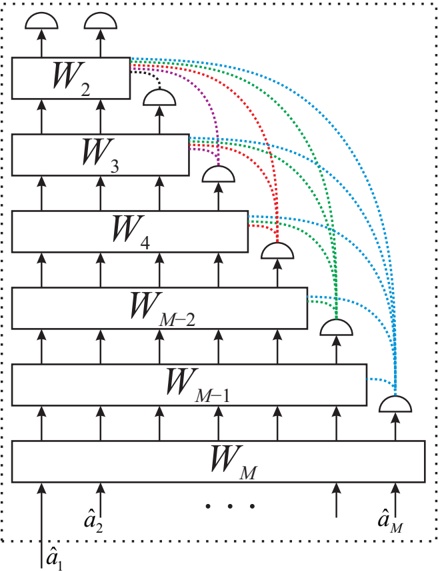

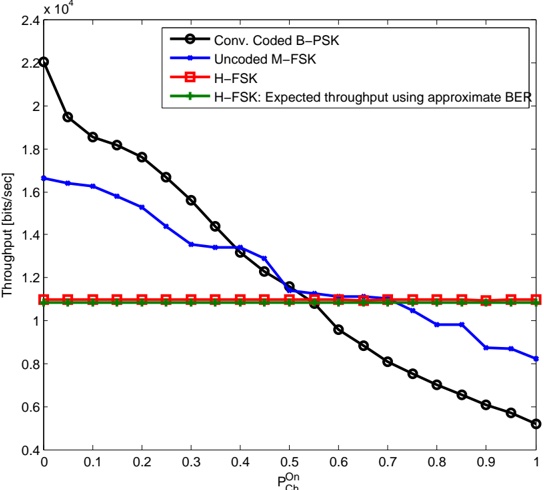

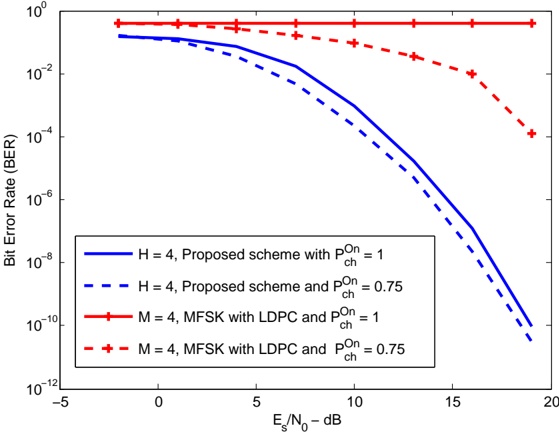

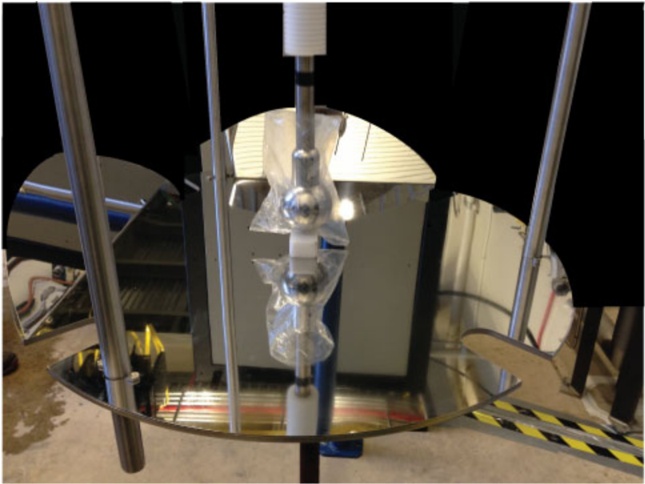

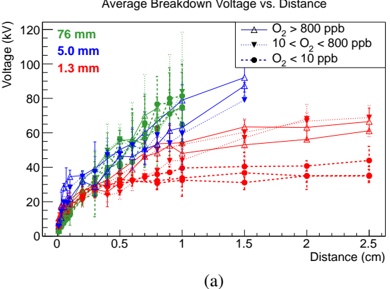

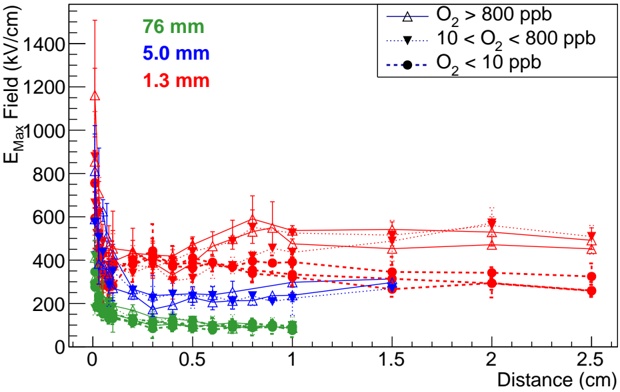

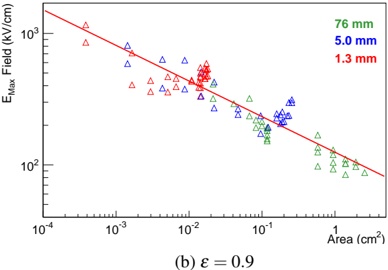

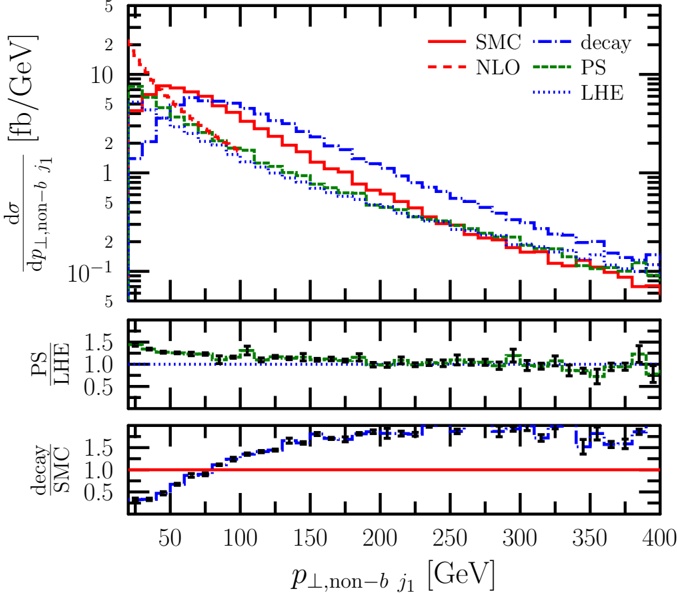

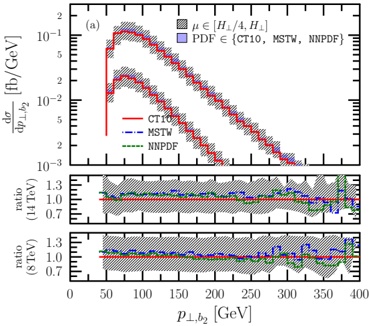

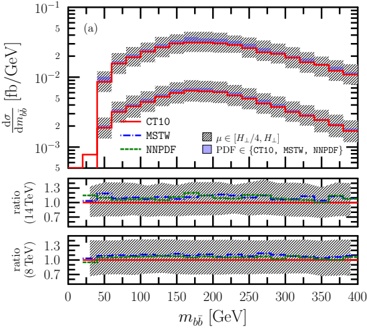

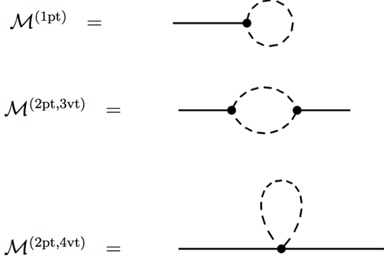

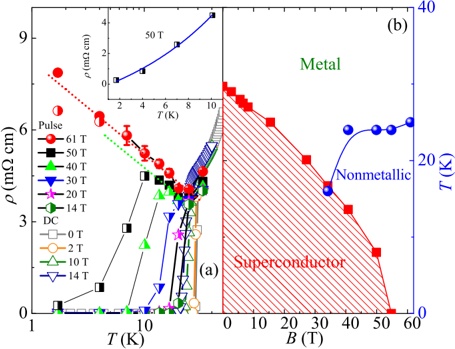

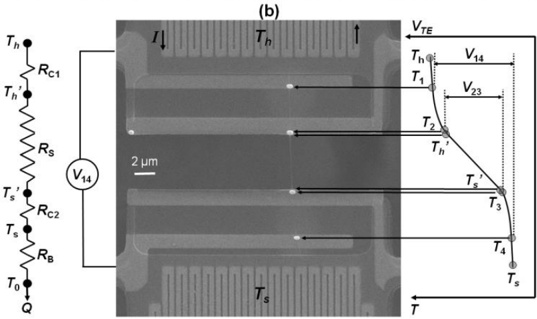

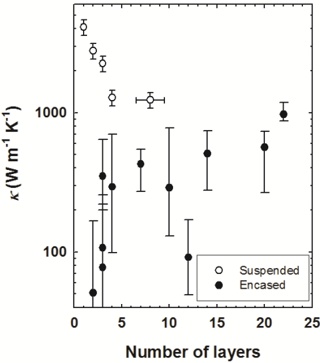

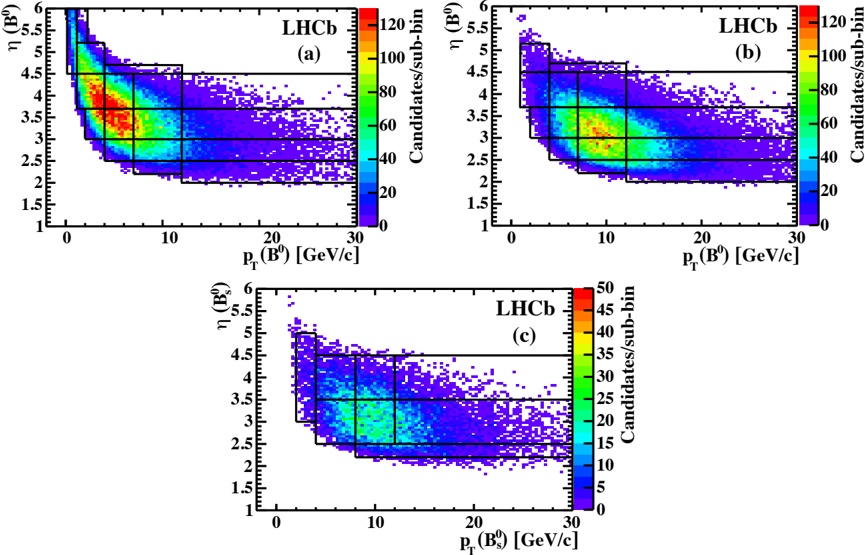

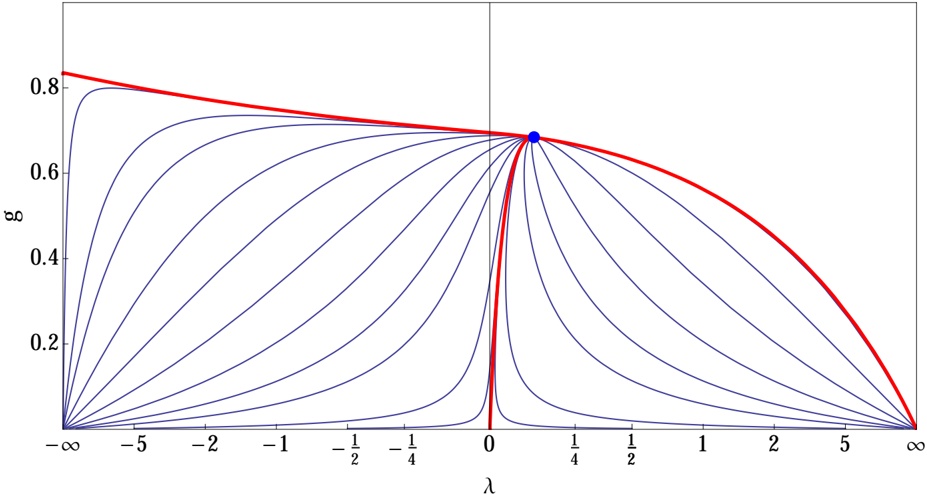

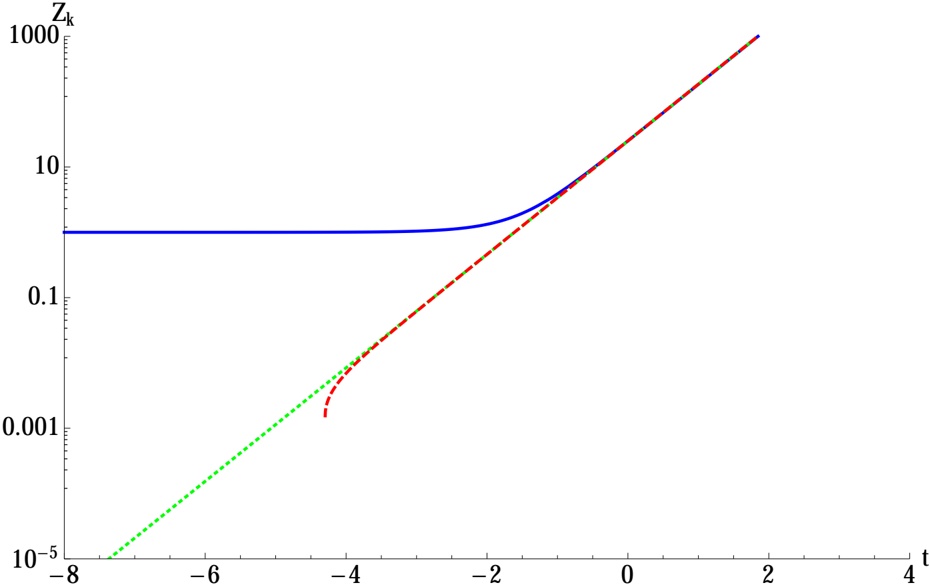

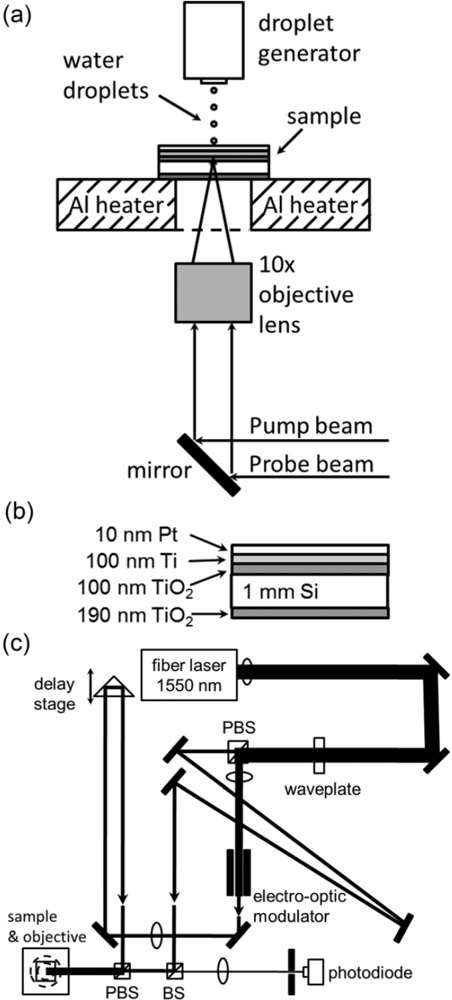

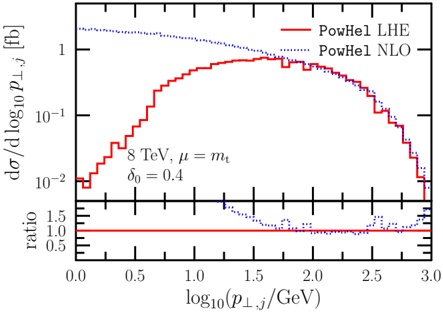

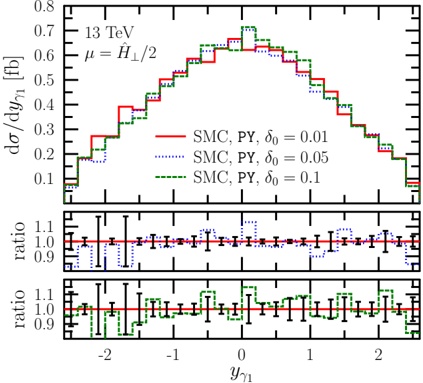

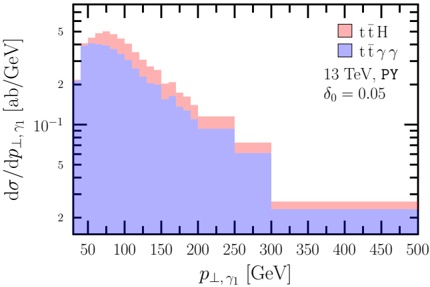

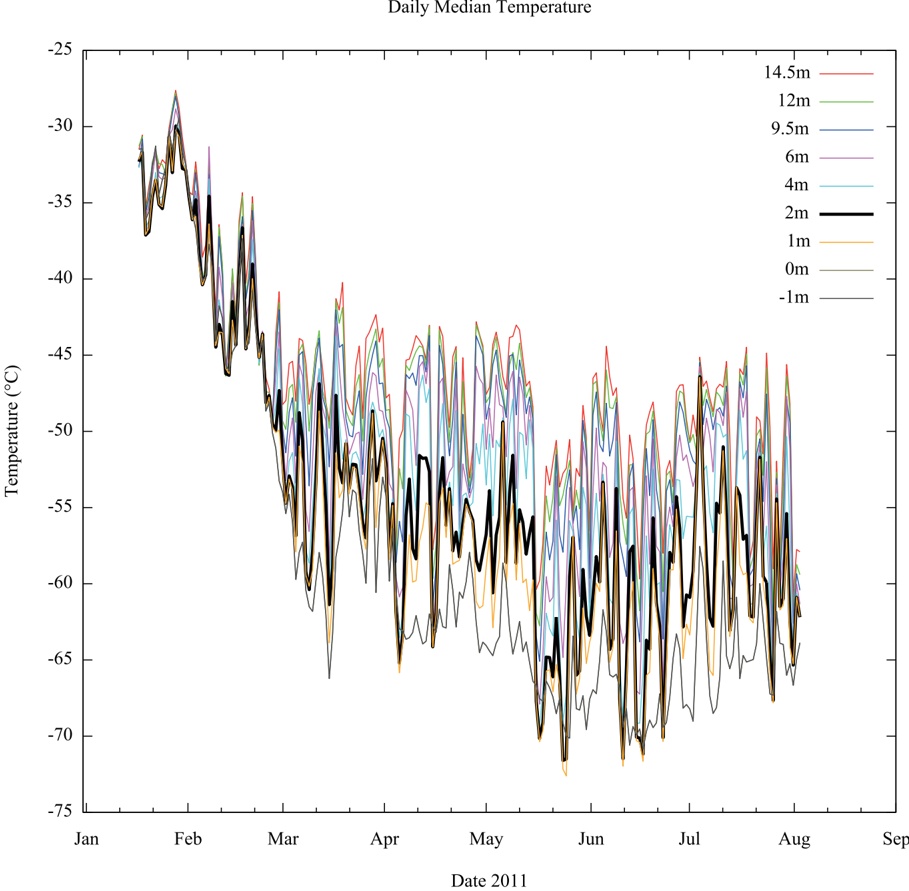

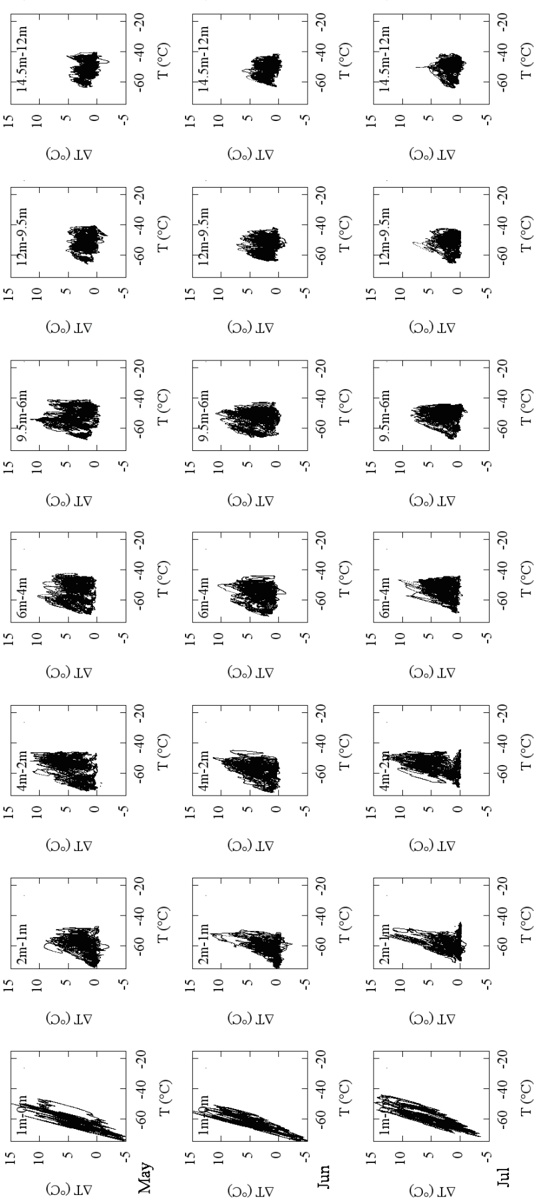

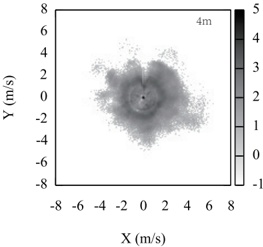

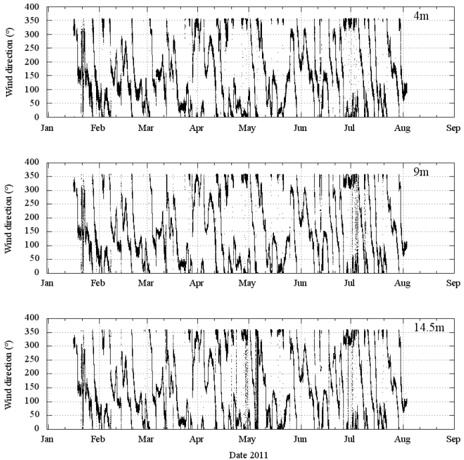

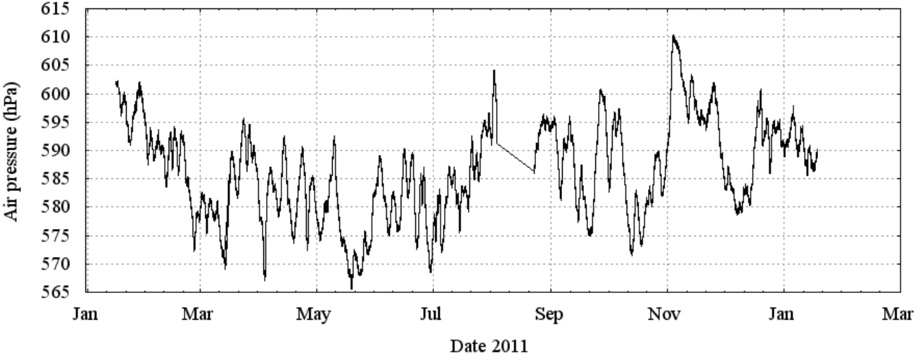

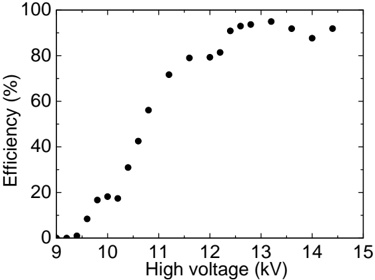

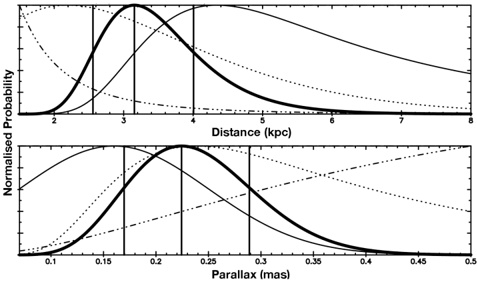

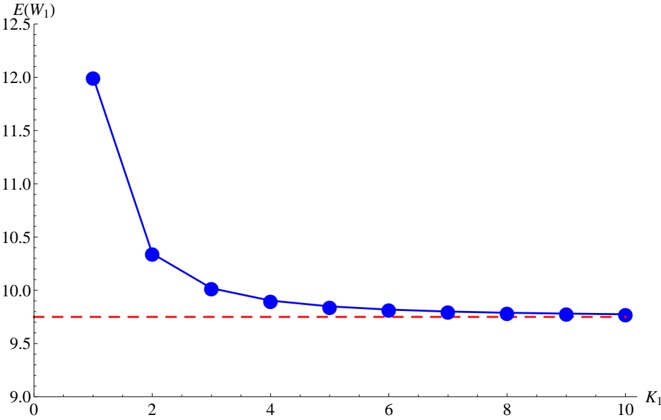

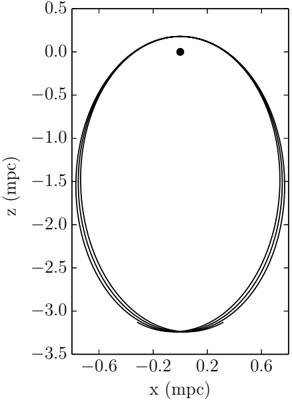

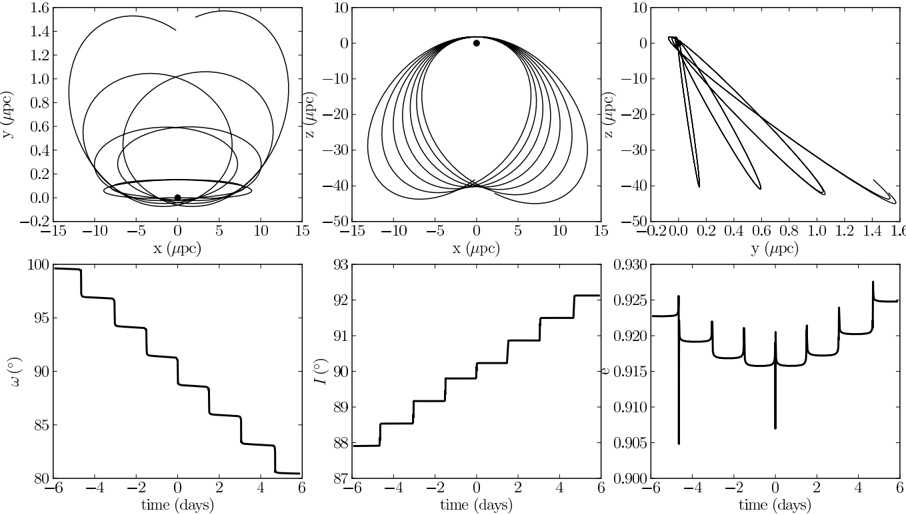

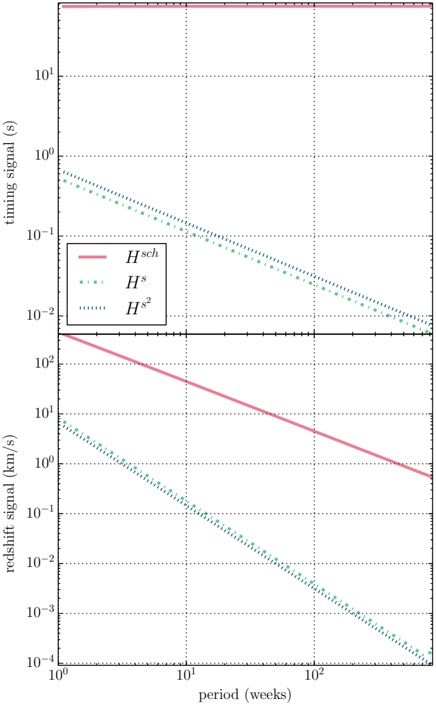

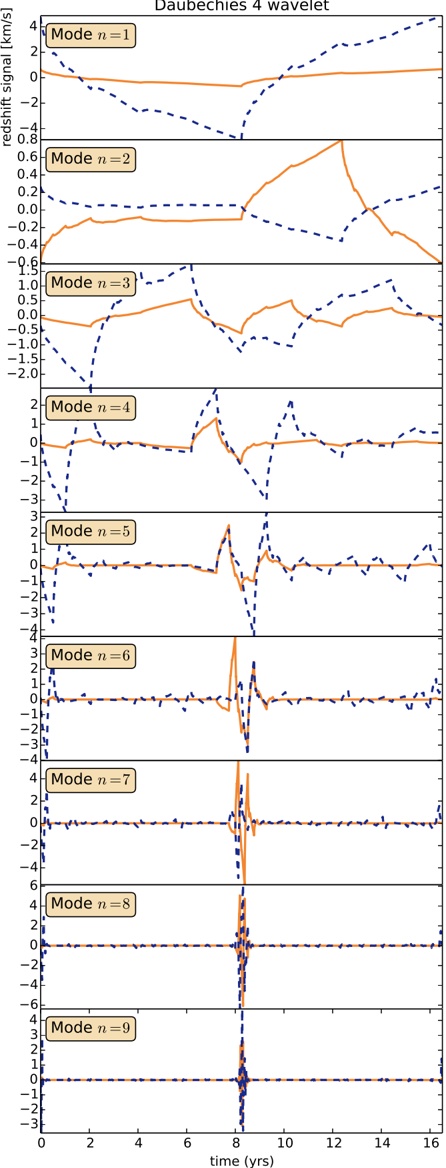

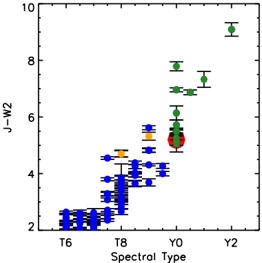

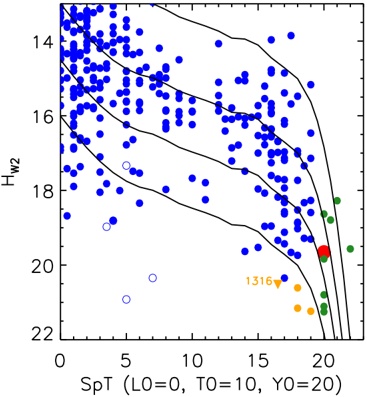

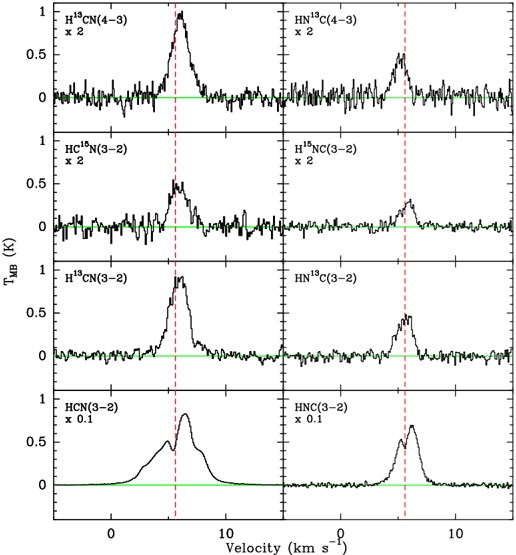

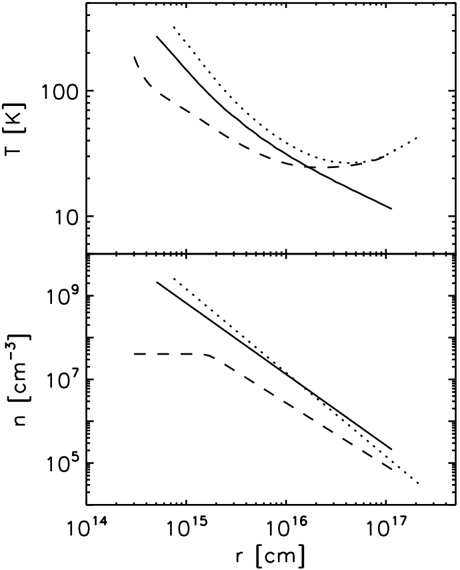

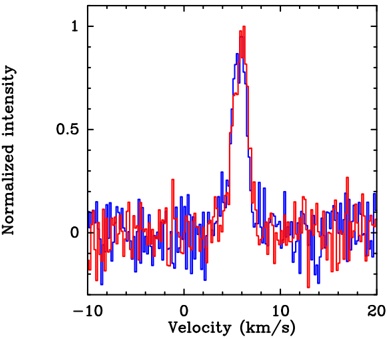

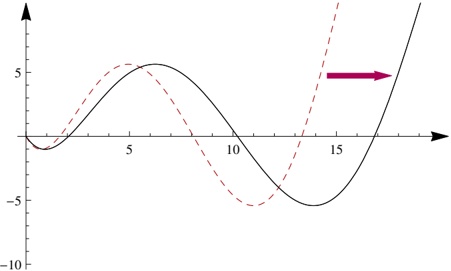

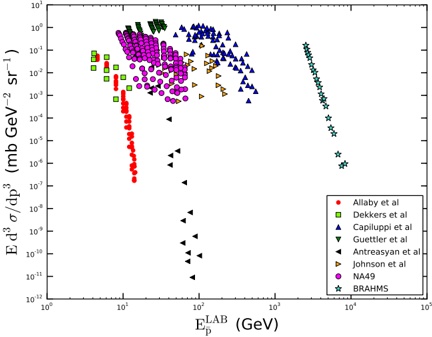

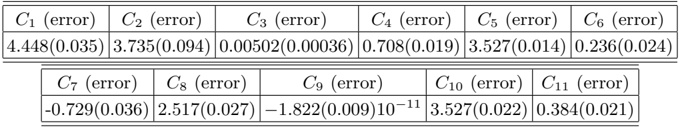

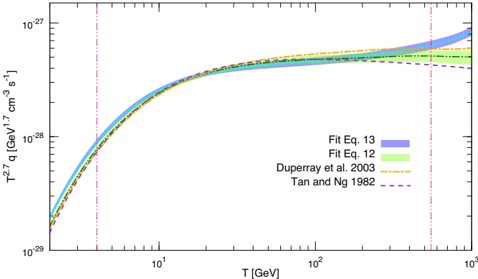

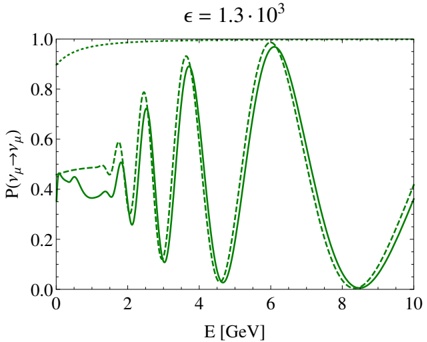

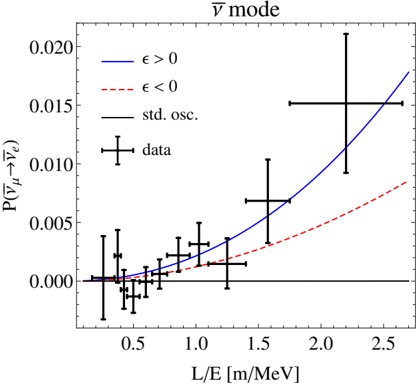

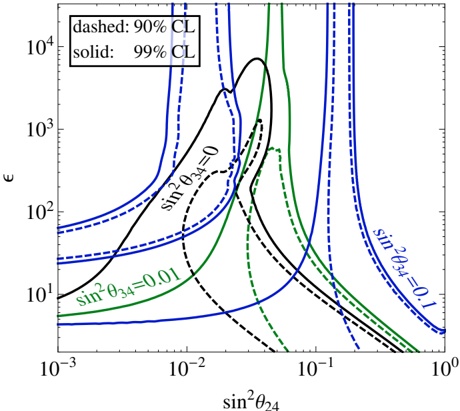

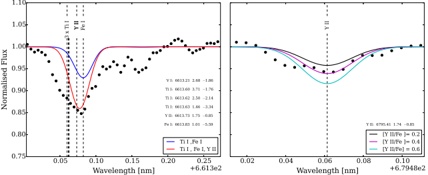

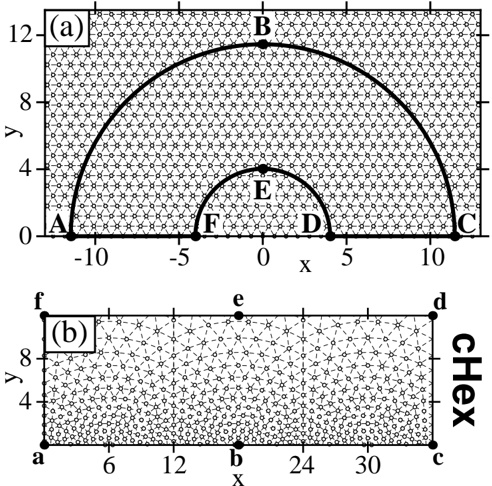

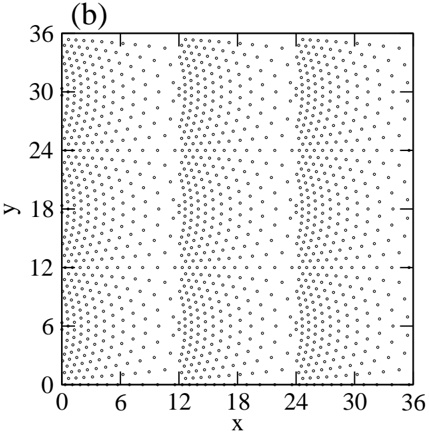

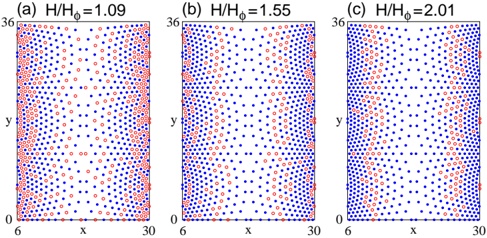

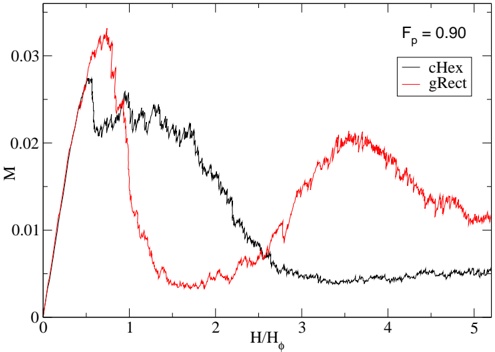

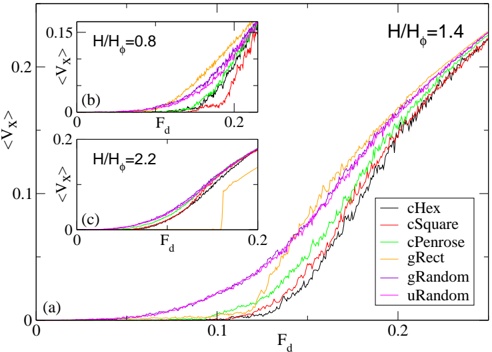

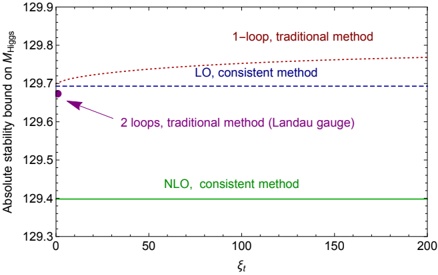

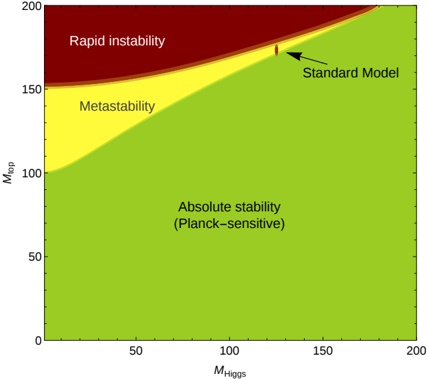

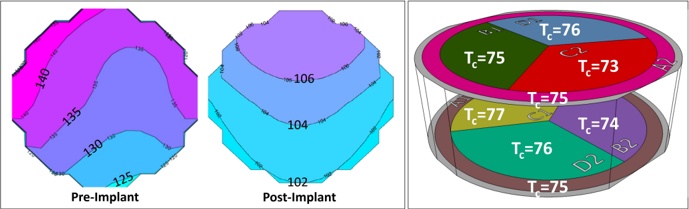

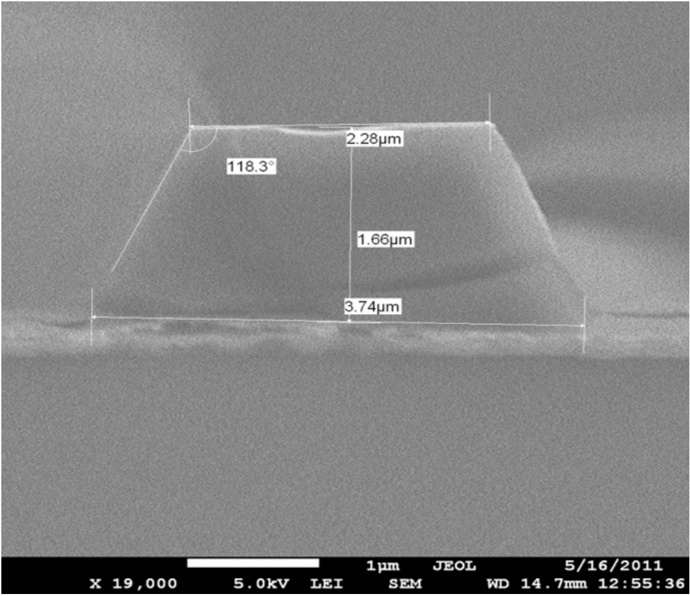

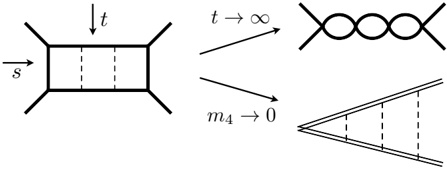

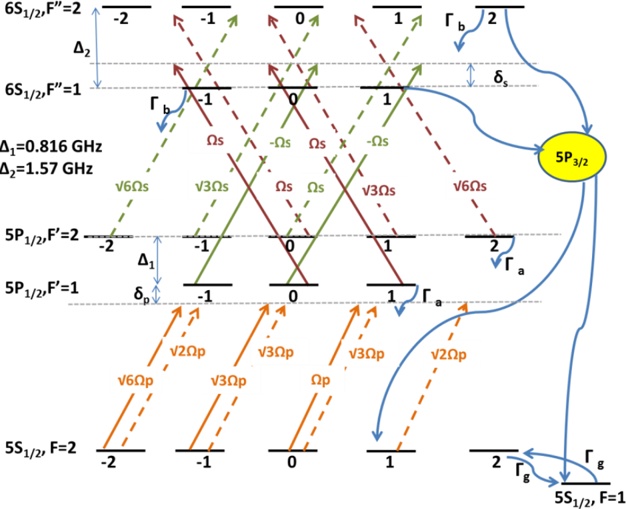

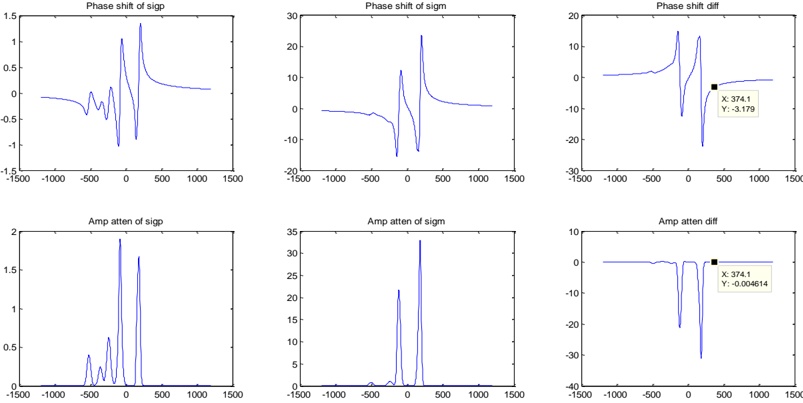

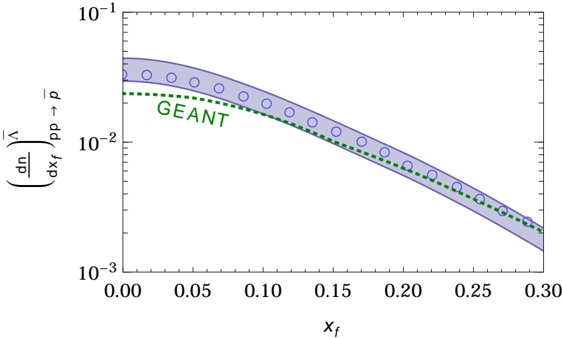

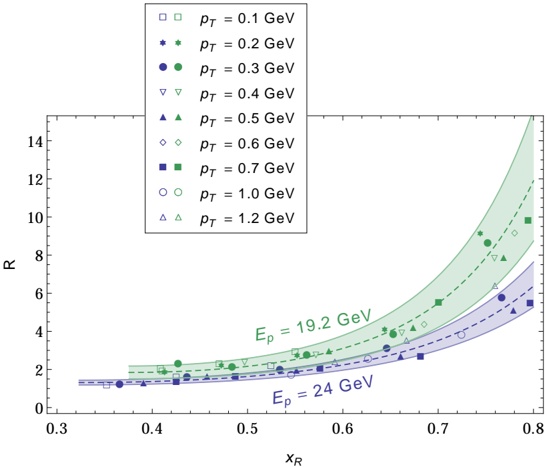

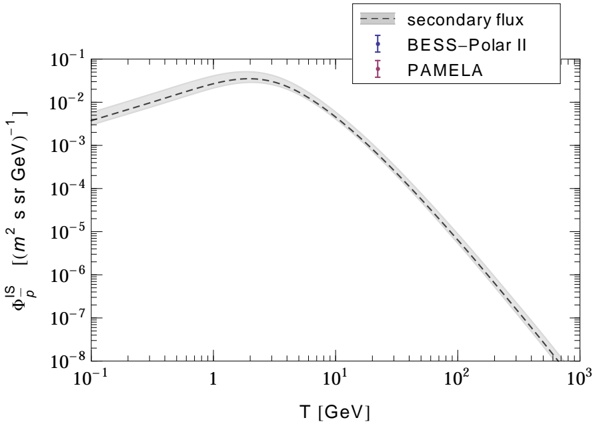

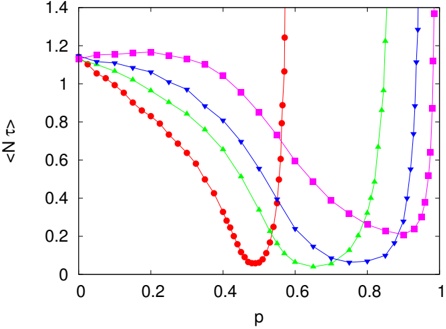

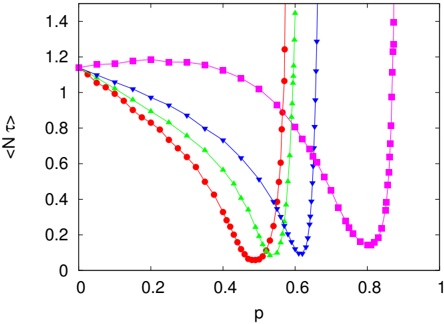

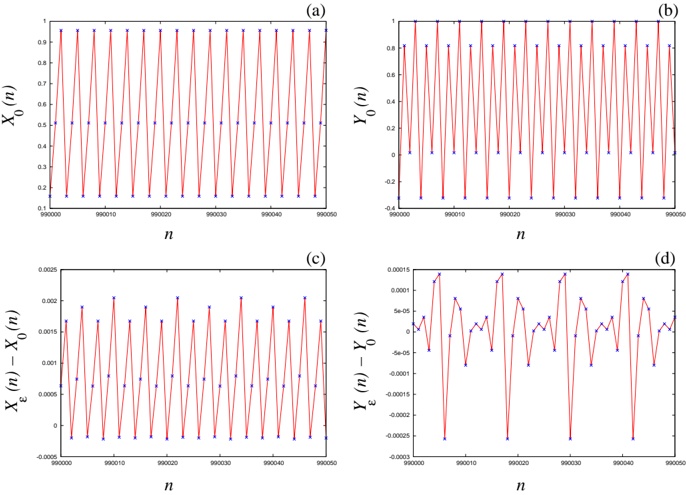

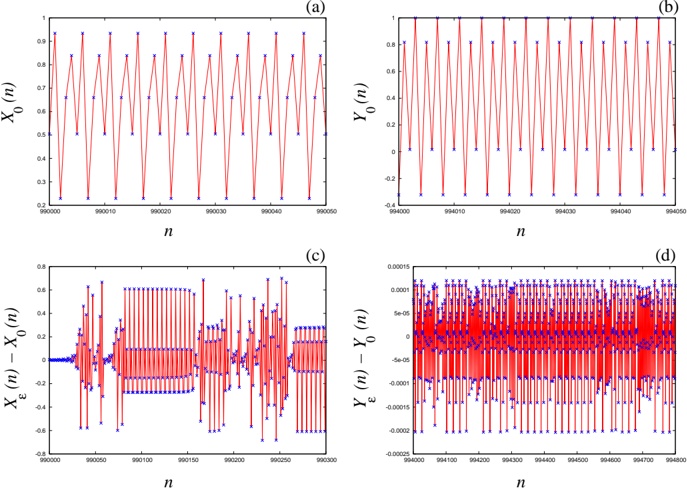

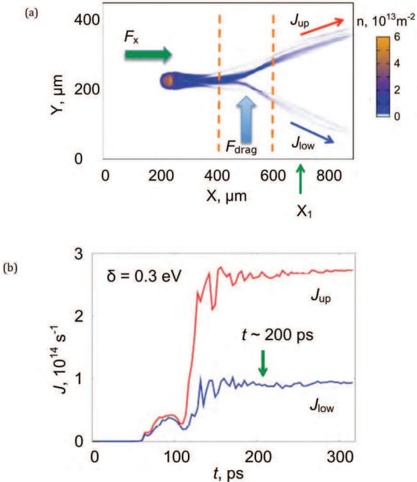

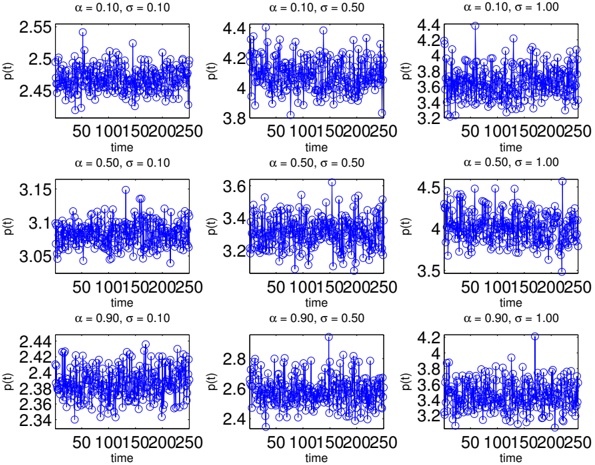

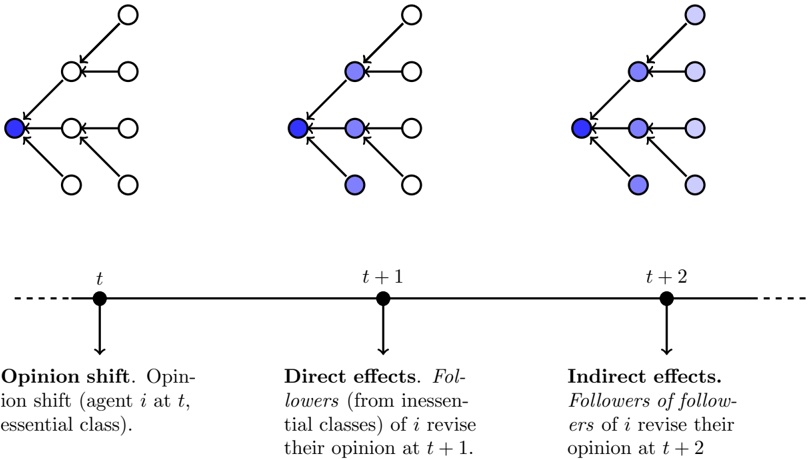

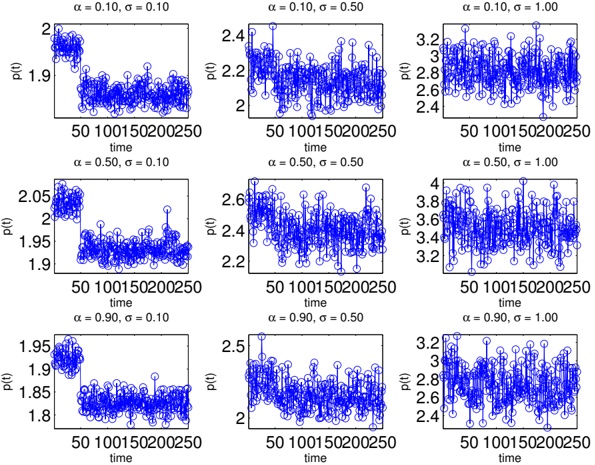

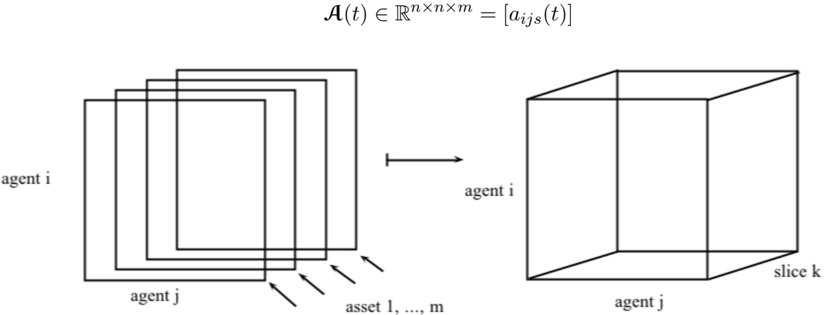

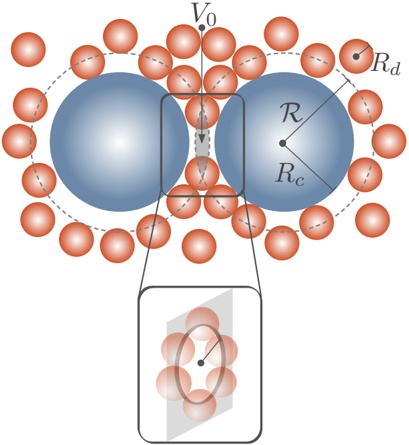

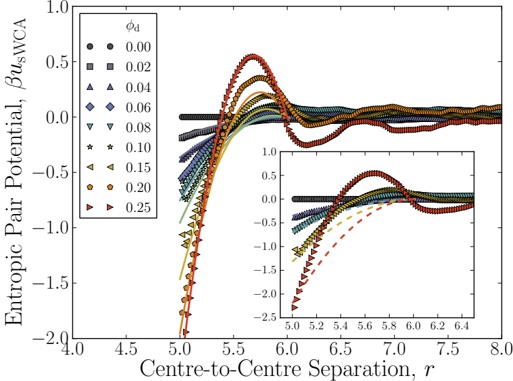

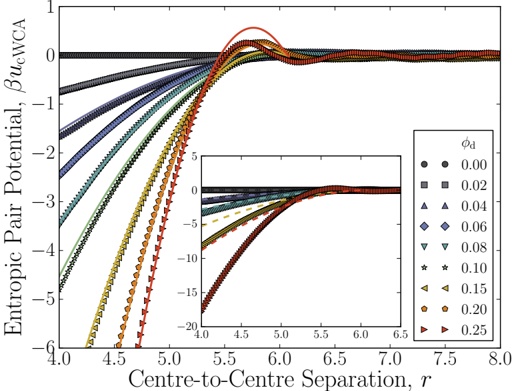

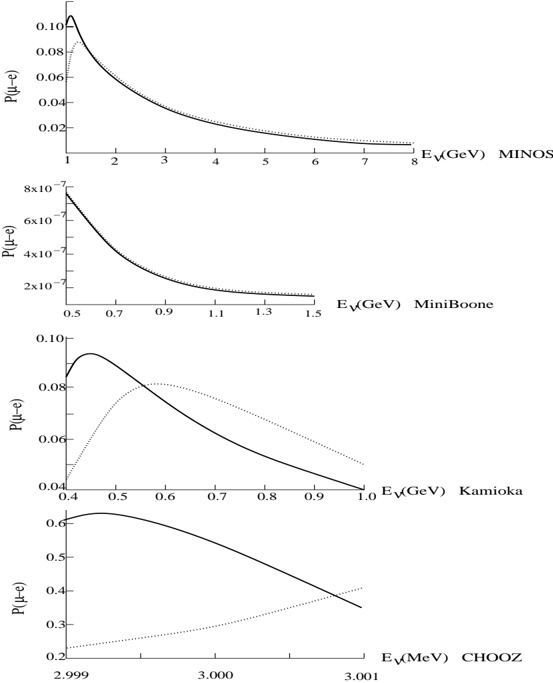

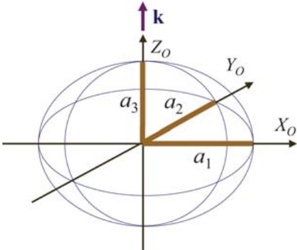

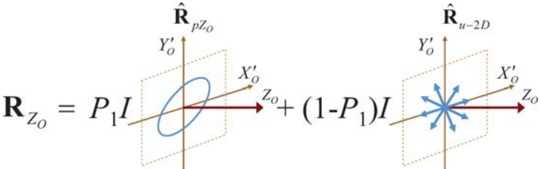

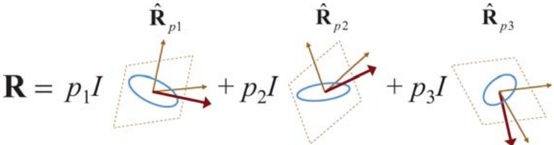

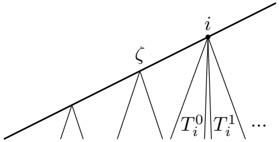

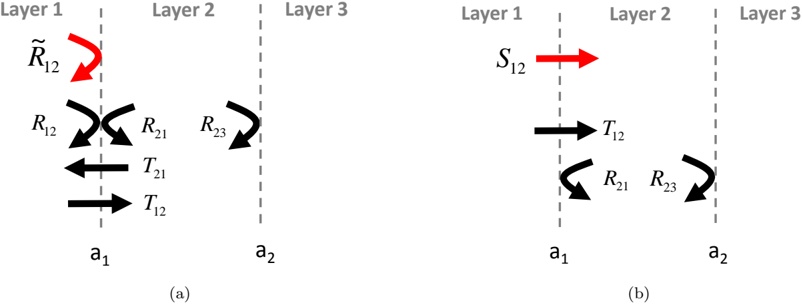

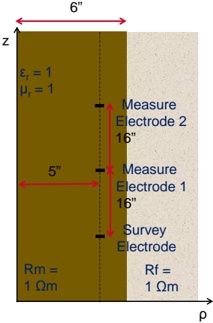

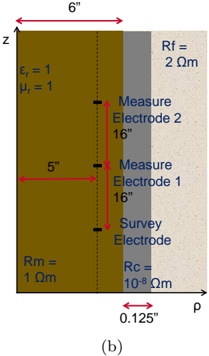

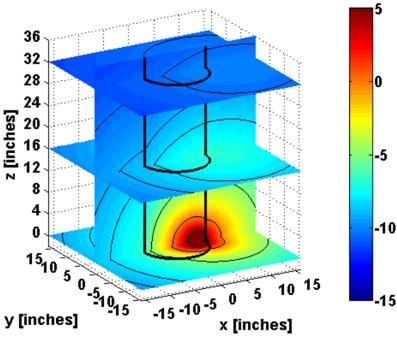

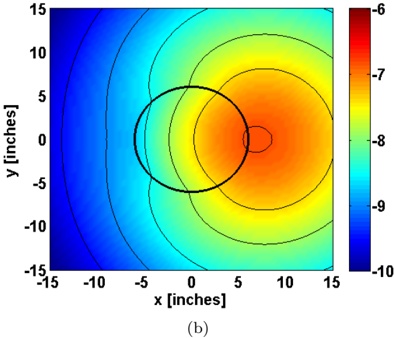

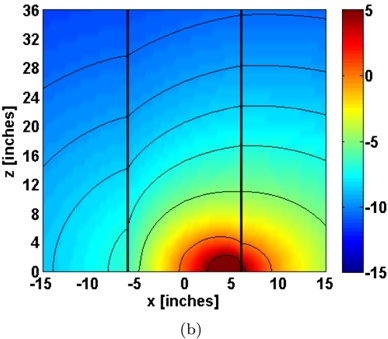

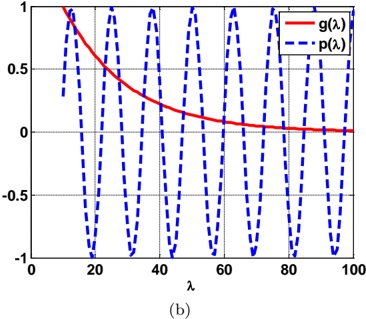

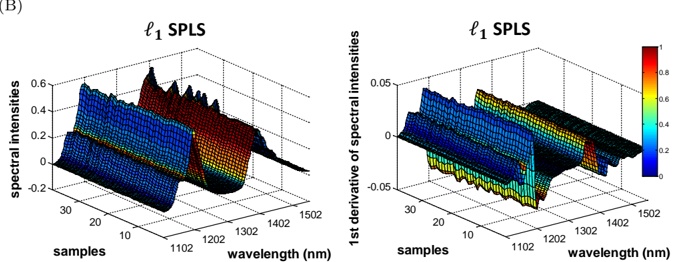

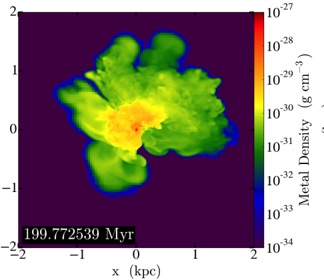

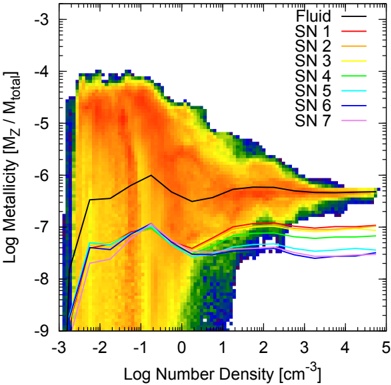

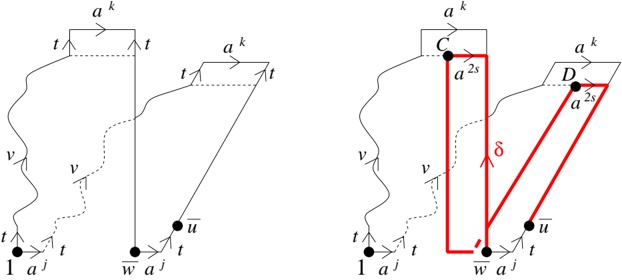

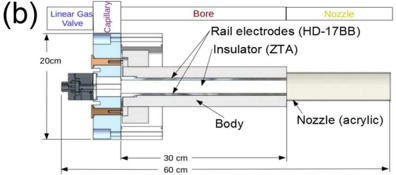

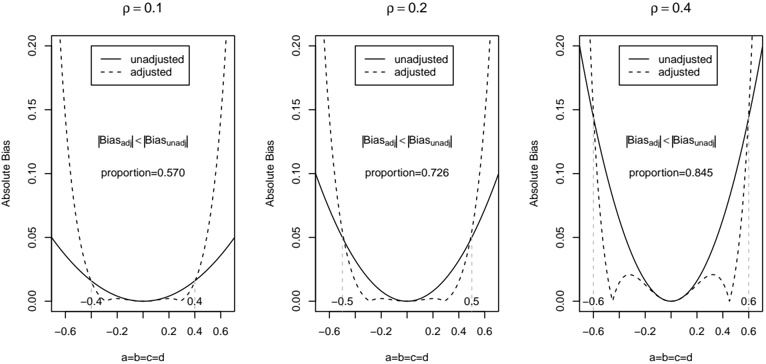

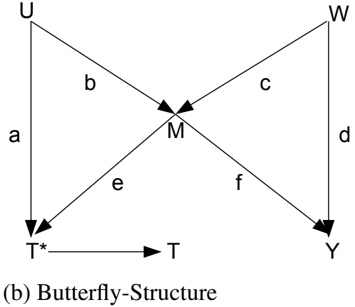

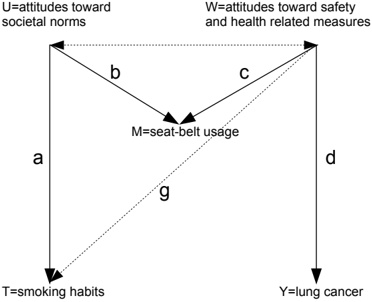

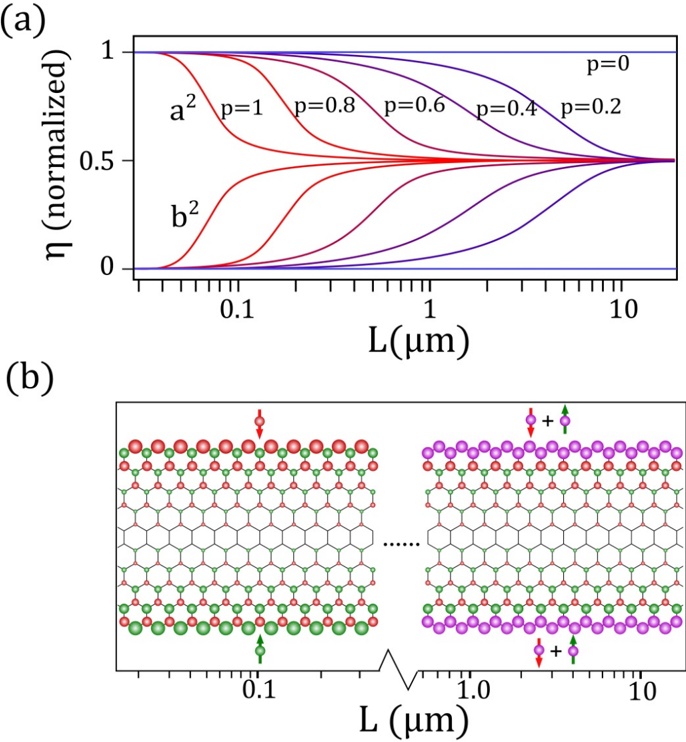

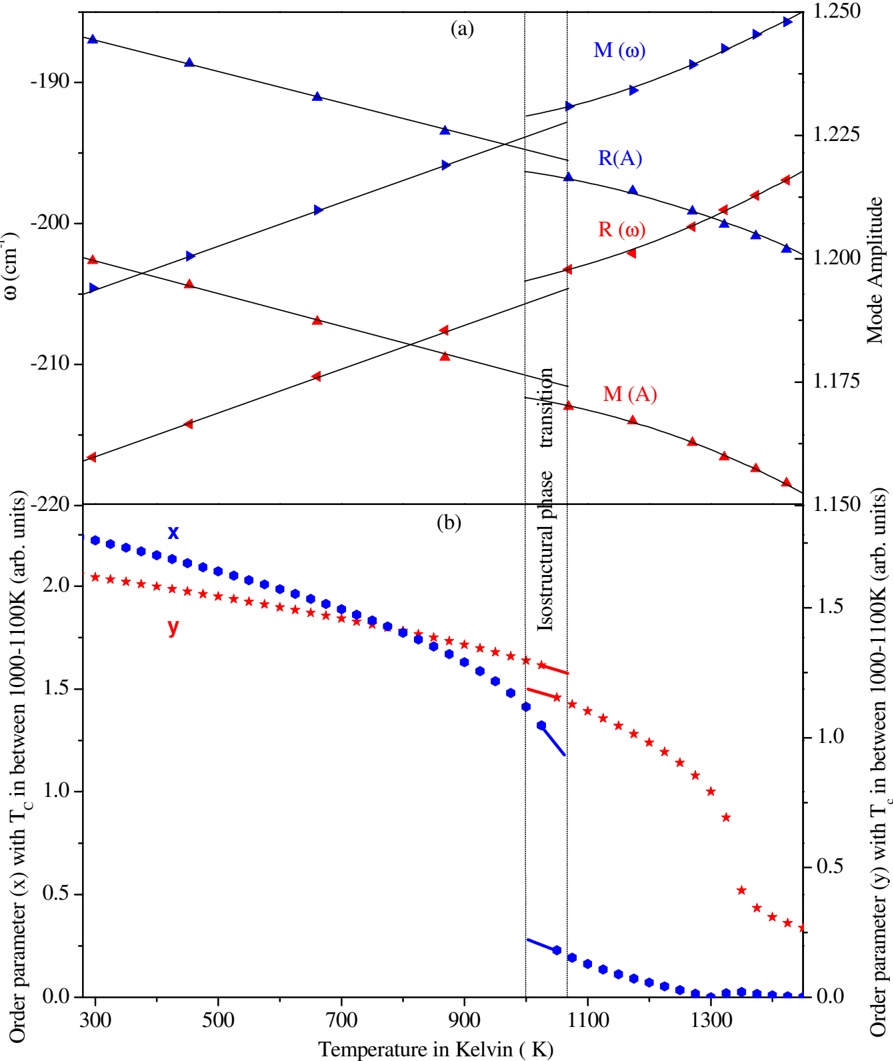

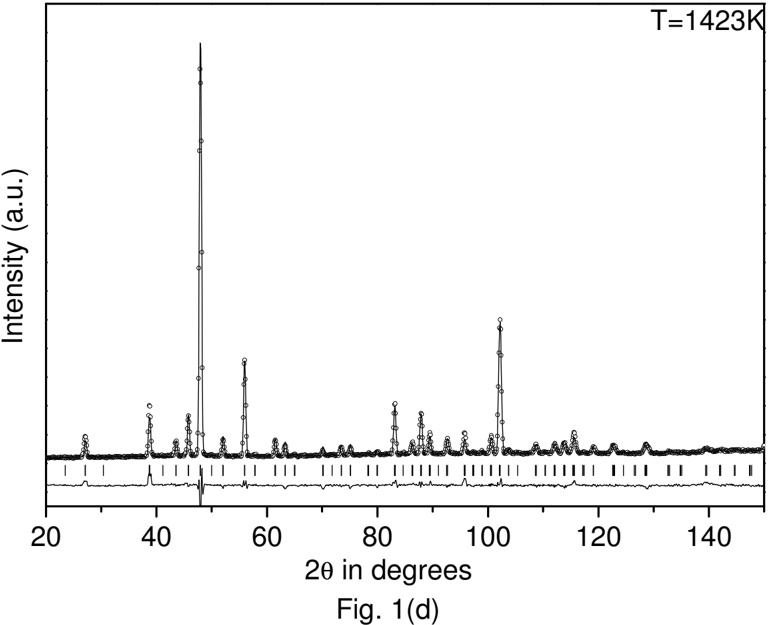

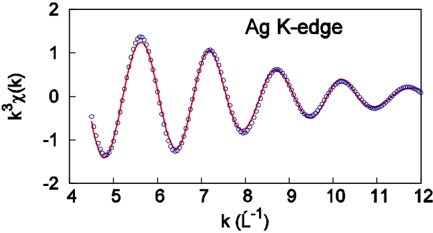

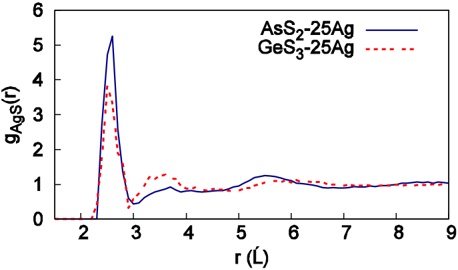

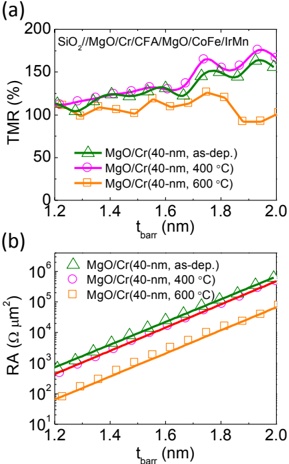

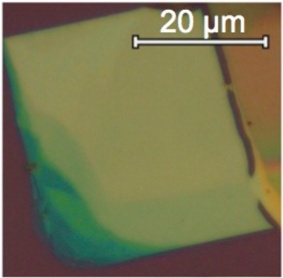

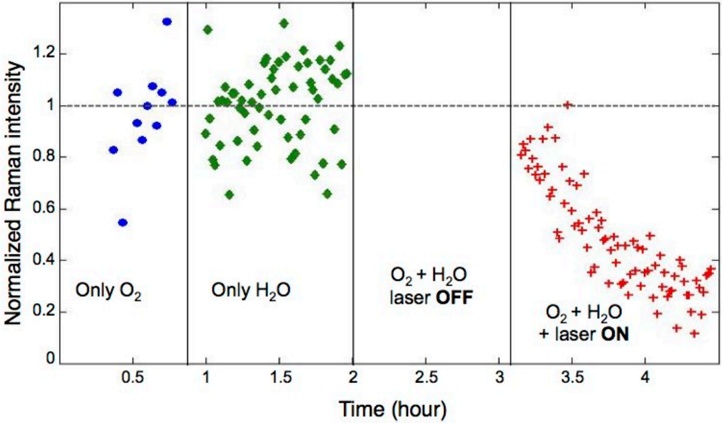

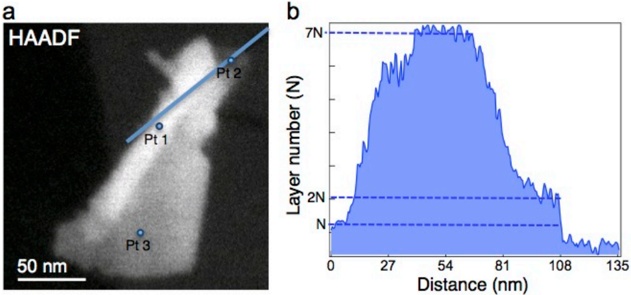

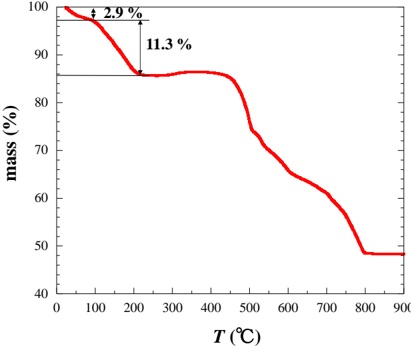

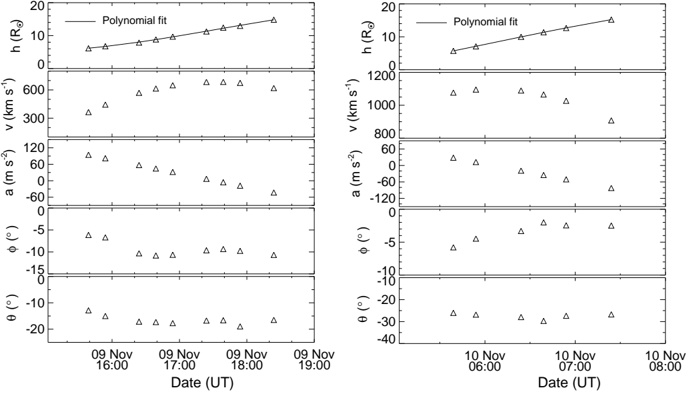

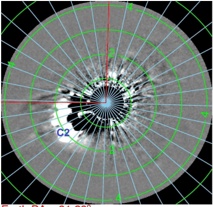

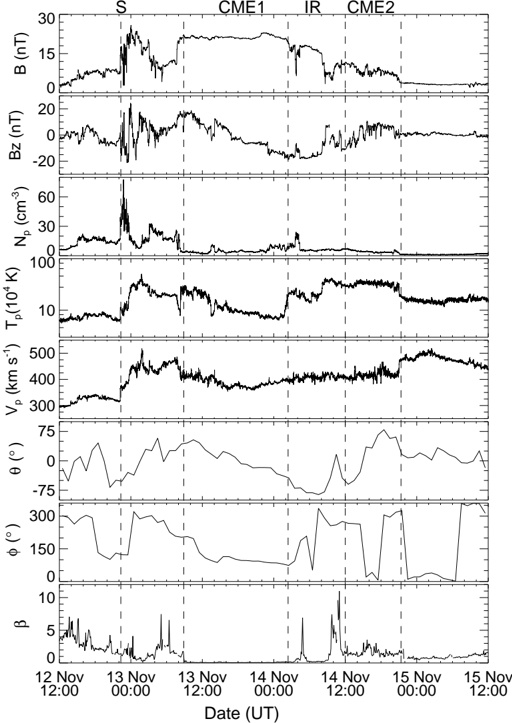

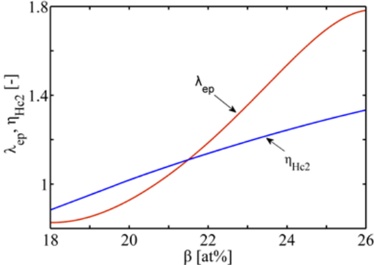

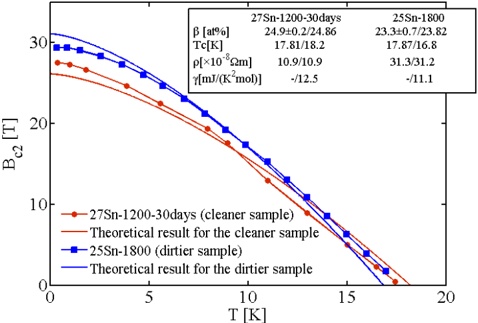

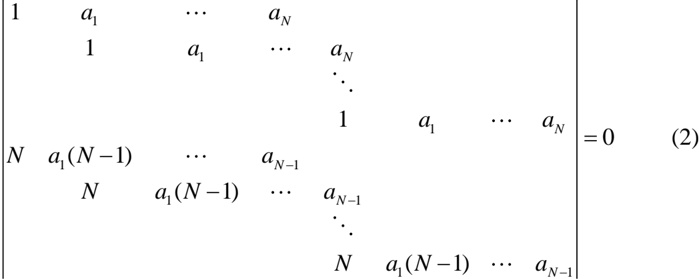

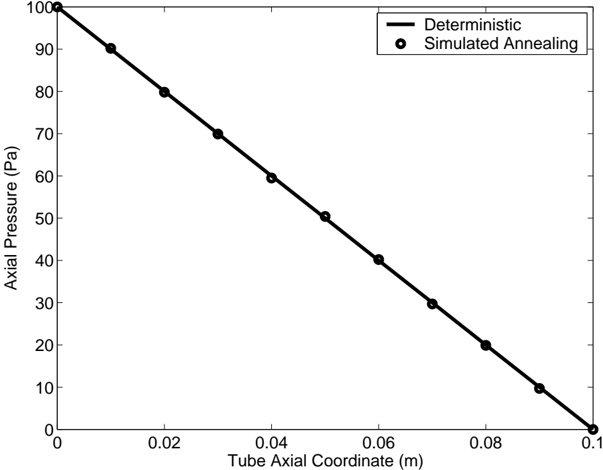

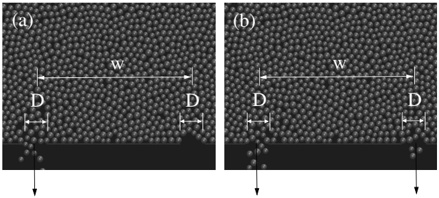

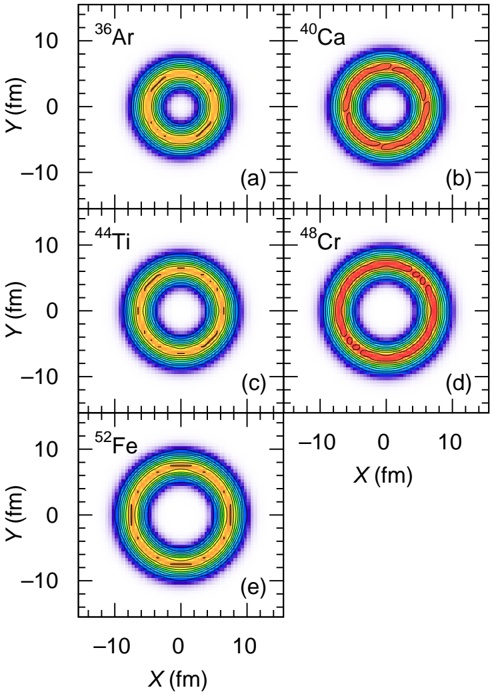

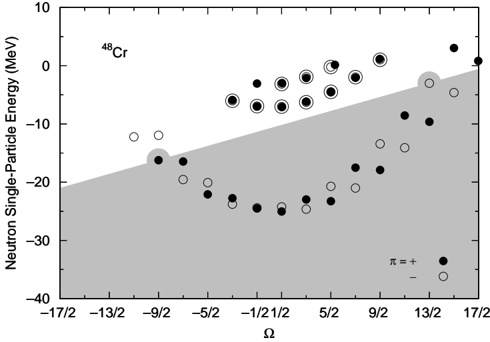

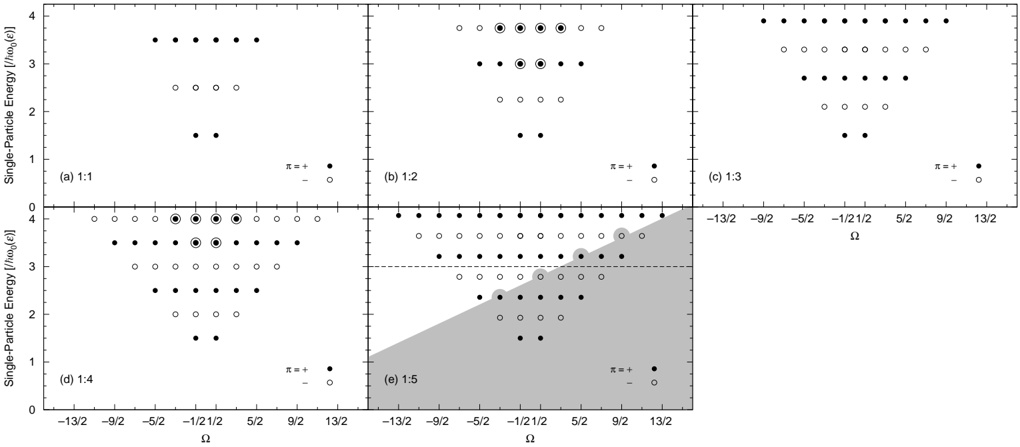

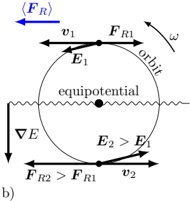

In Figure 3 we compare the membership probabilities from proper-motion and our RV (Section 4.4) measurements, splitting the sample at a radius of 10 ′ due to the large difference in the precisions of the proper-motion data at that radius. Overall we have good agreement between the two studies. A large number of stars have both P µ and P RV = 0% and within 10 ′ we see a large concentration of targets with high RV and proper-motion probabilities. In both plots we note a large population of stars around the perimeter (e.g., the vertical lines at P RV = 0%). These over-densities are due to the vast majority of the stars in both studies falling at either end of the distribution, either 0% or 99%, providing a large population to fill up the edges and leaving very few stars to populate the centers of the plots of Figure 3.

Figure 3. Comparison of cluster membership probabilities from radial-velocity and proper-motion measurements. Proper-motion membership probabilities, P µ , are from Platais et al. (2013). Radial-velocity membership probabilities are determined from Equation (3). Sources within 10 ′ of the cluster center are presented on the left and sources outside of 10 ′ are on the right. Proper-motion membership probabilities outside of 10 ′ have lower precisions, peak at P µ of 63%, and have more inconsistencies with our radial-velocity membership determination.

Platais et al. (2013) choose a membership threshold at a P µ of 4%, but note a substantial overlap between the proper-motion distributions of the cluster and field stars in the direction of NGC 6819. They find that a CMD of stars with P µ ≥ 4% within 10 ′ shows a clean MS, subgiant branch, and RGB. A CMD that includes stars with P µ < 4% shows no distinguishable cluster features.

We also adopt the proper-motion membership threshold of 4%. We do caution that proper-motion information outside of 10 ′ from the cluster center have larger errors and disagree with our membership determinations from RVs more frequently (Figure 3) than for stars within 10 . ′

## 4. RADIAL-VELOCITY STUDY

The details of our RV survey of NGC 6819 including the observing procedure, data reduction, and membership classification are discussed in depth in Hole et al. (2009) and Geller et al. (2008). The following sections summarize the details relevant to the results presented in this paper and provide updated information where appropriate.

sample was based on RV98 and PHOT98 photometry. Cutoffs based on V and ( B -V ) were chosen in order to select the upper MS, giant branch, red clump, and potential blue straggler candidates in NGC 6819. Later, the sample was updated and extended in radius with the addition of K01 and Phot03 photometric studies. Stars without optical photometry (primarily at large radii) were included based on V magnitudes converted from 2MASS J and K information. In this paper, as discussed in Section 2, we have incorporated Y13 V I photometry that provides photometry for 98% of our RV survey. In 2010, we incorporated the proper-motion information from Platais et al. (2013) into our RV survey. Stars identified by Platais et al. (2013) as proper-motion non-members, P µ < 4%, were moved to the lowest priority for observations.

## 4.1. Observations, Data Reduction, and Precision

The WOCS RV target sample for NGC 6819 has 3895 stars that span 1 ◦ on the sky centered at α = 19 41 h m 17 s . 5, δ = +40 11 47 ◦ ′ ′′ (J2000). Hole et al. (2009) discuss the target selection and evolution of the RV target sample in great detail. In brief, the initial target

Observations of NGC 6819 with the Hydra MultiObject Spectrograph (MOS; Barden et al. 1994) on the WIYN 7 3.5 m telescope began in 1998 June and are still ongoing. We have almost 14,000 spectra for over 2600 stars. These observations are augmented with 733 RV measurements for 170 stars taken at the HarvardSmithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) facilities between 1988 May and 1995 by R. D. Mathieu & D. W Latham (Hole et al. 2009).

The WIYN data include for each configuration: three

7 The WIYN Observatory is a joint facility of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Indiana University, Yale University, and the National Optical Astronomy Observatory.

Table 1 Radial-velocity Measurements

| ID | HJD - 2400000 | Telescope a | RV 1 | Correlation Height 1 | O - C 1 | RV 2 | Correlation Height 2 | O - C 2 | Phase |

|------|-----------------|---------------|----------|------------------------|-----------|----------|------------------------|-----------|---------|

| 9030 | | | | | | | | | |

| | 55374.6633 | W | 1.874 | 0.89 | 4.00 | - 19.272 | 0.63 | 3.44 | 0.234 |

| | 55374.7375 | W | - 13.202 | 0.89 | 0.01 | · · · | · · · | · · · | 0.257 |

| | 55375.6625 | W | - 88.546 | 0.63 | - 3.10 | 60.357 | 0.57 | 5.29 | 0.545 |

| | 55375.7354 | W | - 80.345 | 0.72 | 2.46 | 54.662 | 0.65 | 2.06 | 0.568 |

| | 55376.6627 | W | 32.298 | 0.68 | 3.05 | - 50.376 | 0.56 | 1.62 | 0.856 |

| | 55376.7367 | W | 42.208 | 0.73 | 3.55 | - 59.876 | 0.54 | 0.90 | 0.879 |

| | 55412.6959 | W | 58.410 | 0.73 | - 2.79 | - 80.087 | 0.61 | 1.73 | 0.066 |

| | 55413.6906 | W | - 62.518 | 0.73 | 0.39 | 37.516 | 0.62 | 3.49 | 0.375 |

| | 55414.6935 | W | - 45.001 | 0.76 | 3.83 | 23.552 | 0.63 | 2.67 | 0.687 |

| | 55440.8442 | W | 11.868 | 0.81 | - 1.99 | - 34.090 | 0.64 | 3.54 | 0.822 |

a The observatory at which the observations were taken, using 'C' for CfA facilities and 'W' for the WIYN 3.5 m.

(This table is available in its entirety in machine-readable and Virtual Observatory (VO) forms in the online journal. A portion is shown here for guidance regarding its form and content.)

science exposures, one 100 s dome flat, and two 300 s thorium -argon emission lamp spectra, one taken before and one taken after the science exposures. The science observations are split into three integrations of equal time for cosmic ray rejection. All the image processing is done within IRAF where the data are bias subtracted and dispersion corrected, and the extracted spectra are flat-fielded, throughput corrected, and sky subtracted.

as single stars. We quantify our detection completeness for binaries using the Monte Carlo analysis described in Section 8.

RVs for single-lined stars are derived from the centroid of a one-dimensional cross-correlation function (CCF) with an observed solar template, converted to a heliocentric velocity, and corrected for the unique fiber offsets of the Hydra MOS. RVs for double-lined stars are derived using two -dimensional correlation (TODCOR) and we provide more details in Section 5.2. The χ 2 analysis of Hole et al. (2009) finds the precision for NGC 6819 data to be σ WIYN = 0.4 km s -1 and σ CfA = 0.7 km s -1 , which we have confirmed remains true for the additional RVs presented here.

We present all of our RV measurements for each star in Table 1, along with the Heliocentric Julian Date (HJD) of the observation and the height of the CCF. For binary stars with completed orbital solutions we also include the RV residual and the orbital phase of the observation.

## 4.2. Velocity Variables

We define velocity variables stars as having RV standard deviations (the external error, e ) greater than four times the precision (the internal error, i ) or e/i > 4 (Geller et al. 2008). We take into account the different data precisions if a star has RV measurements from both observatories using the following:

$$\left ( \frac { e } { i } \right ) ^ { 2 } = \frac { N ^ { 2 } } { N - 1 } \frac { \sum _ { i } ^ { N } \left ( \mathrm R V _ { i } - \overline { \mathrm R V } \right ) ^ { 2 } / \sigma _ { i } ^ { 2 } } { \sum _ { i } ^ { N } \sigma _ { i } ^ { 2 } \sum _ { i } ^ { N } 1 / \sigma _ { i } ^ { 2 } }, \quad ( 1 ) \quad \text{the} \\ \text{where} \, \mathrm R V \text{ is the mean RV weighted by the precision val-} \quad \text{with} \quad \text{$two$}$$

where RV is the mean RV weighted by the precision values of each observatory:

$$\overline { R V } = \frac { \sum _ { i } ^ { N } R V _ { i } / \sigma _ { i } ^ { 2 } } { \sum _ { i } ^ { N } 1 / \sigma _ { i } ^ { 2 } }. \quad ( 2 ) \quad \begin{pmatrix} t t \\ \text{al} \\ \text{t} \\ \text{ju} \\ \text{S}! } \end{pmatrix}$$

For a star with three or more observations we calculate the RV and e/i and classify it as single or velocity variable. Given our RV measurement precisions binaries that are long-period and/or low-amplitude may be classified

In Table 2, we present the coordinates, V I photometry, number of observations at each observatory, RV, RV standard error, e/i , membership probabilities, and membership classification for all of the stars we have observed in NGC 6819 as of 2014 February. For each binary star with a completed orbital solution the center-of-mass velocity, γ , its error, and whether it is a single- or doublelined binary are also listed in Table 2.

## 4.3. Completeness

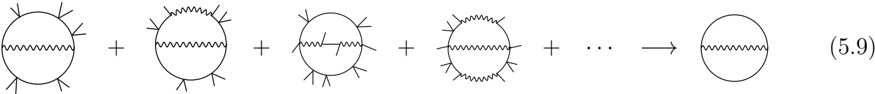

The entire target sample is comprised of 3895 stars with RV measurements from the CfA dating back to 1988 and WIYN observations beginning in 1998. Over the entire course of our survey we constantly reevaluate the observing priority of every star. Based on Monte Carlo analyses and observing efficiency arguments (Mathieu 1983, Geller & Mathieu 2012) a star is classified as single or velocity variable after three observations. In general, stars classified as single are given a low priority for further observation. Stars that are classified as velocity variable are given a high observing priority and are observed until an orbital solution is determined. However, stars identified as proper-motion non-members, P µ < 4%, are given the lowest observing priority.

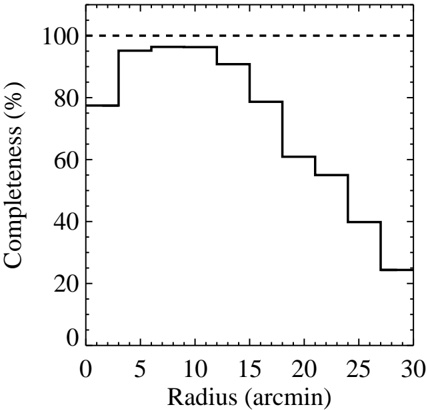

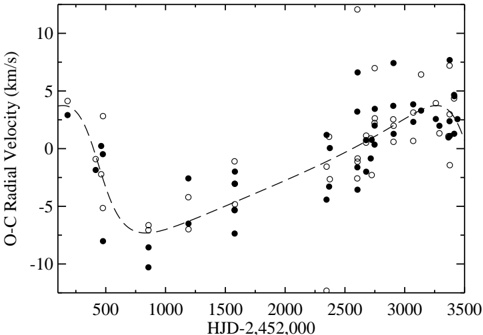

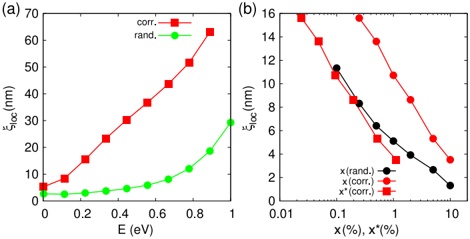

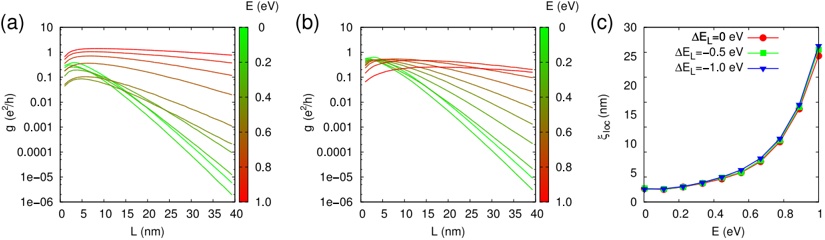

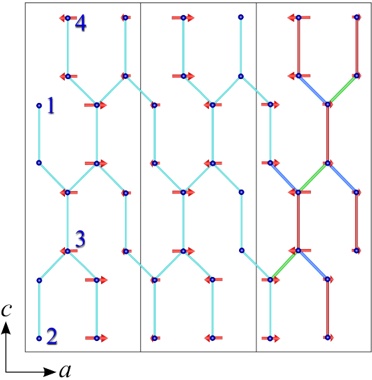

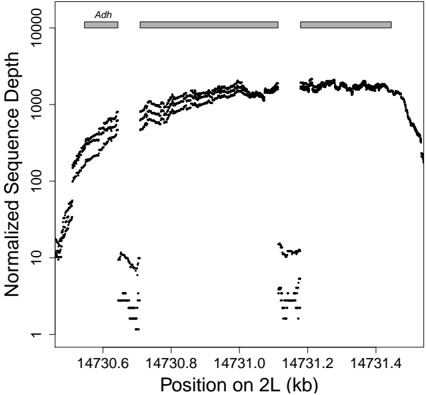

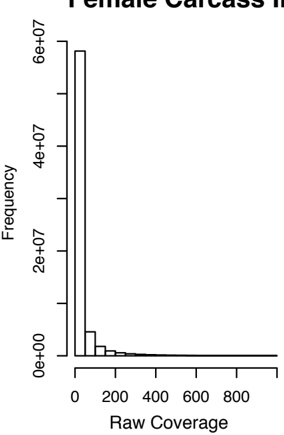

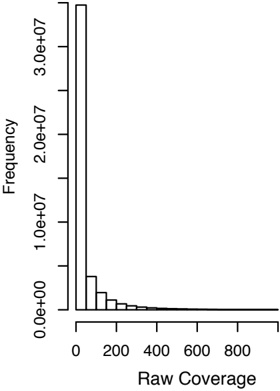

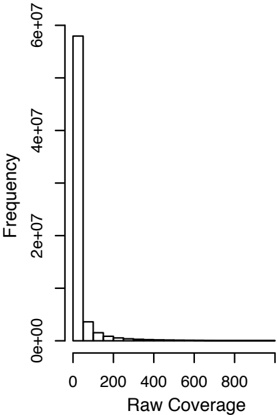

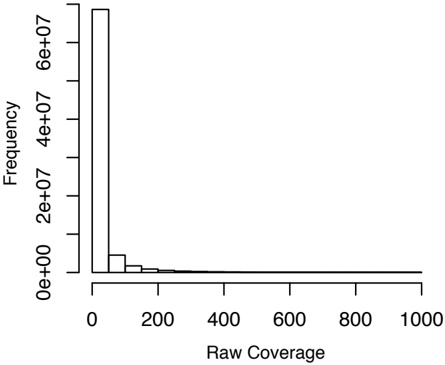

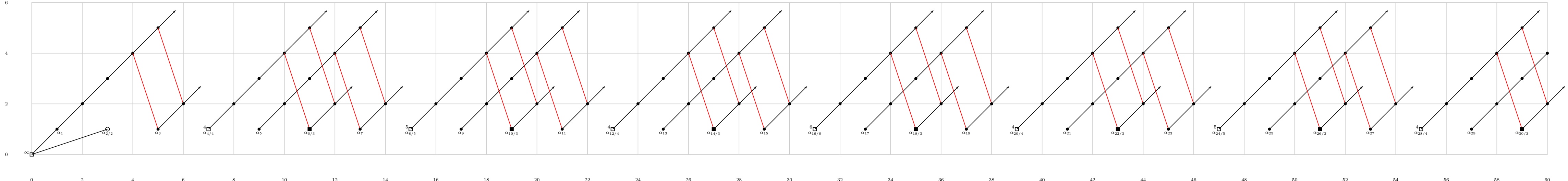

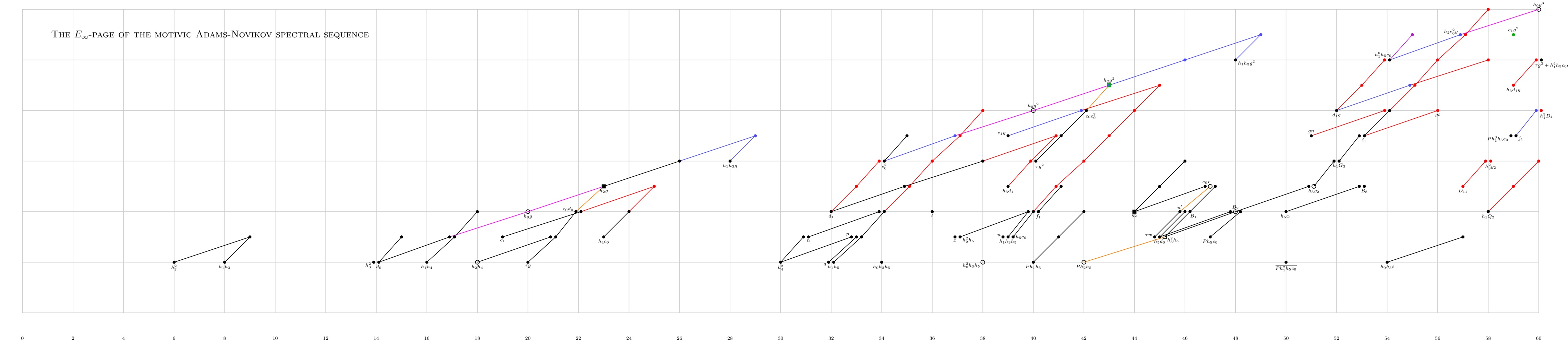

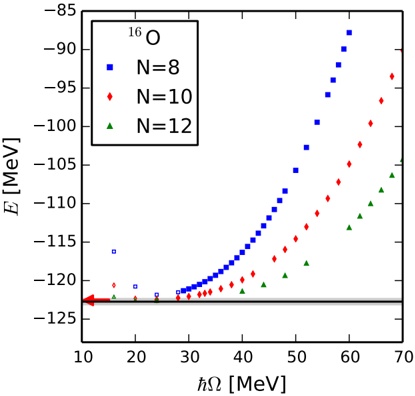

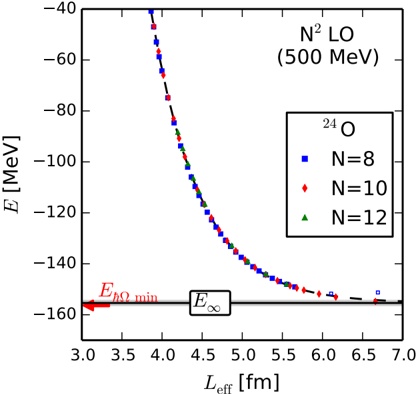

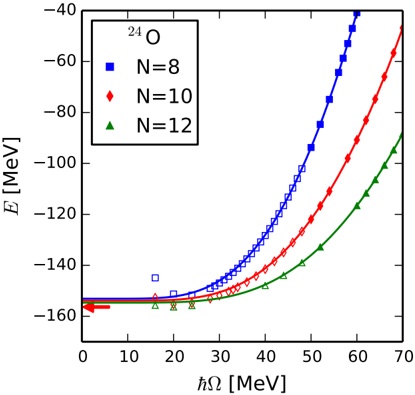

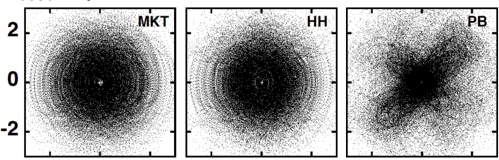

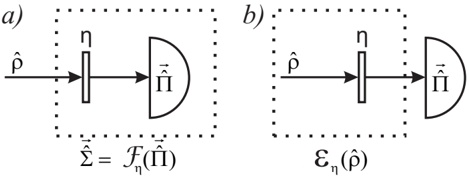

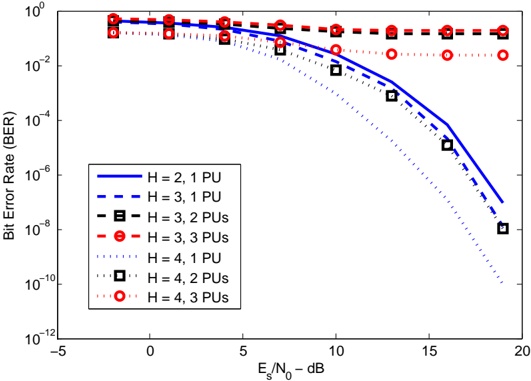

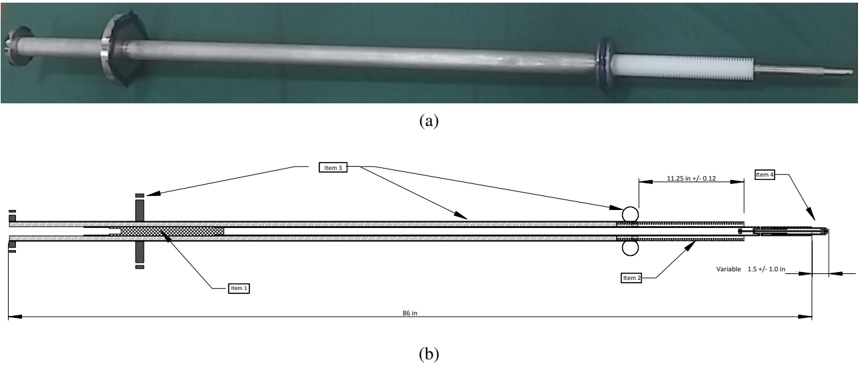

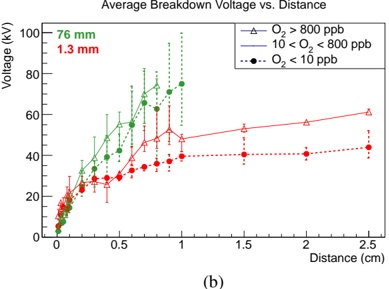

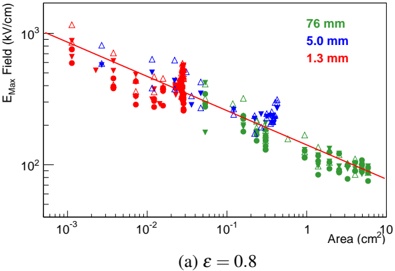

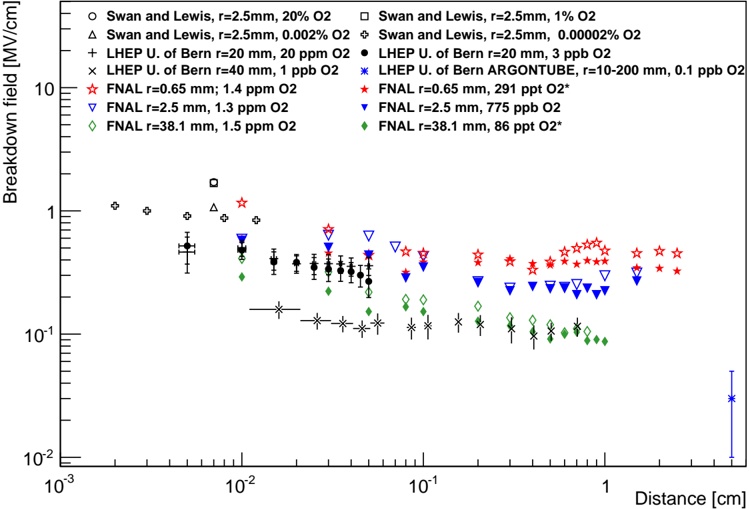

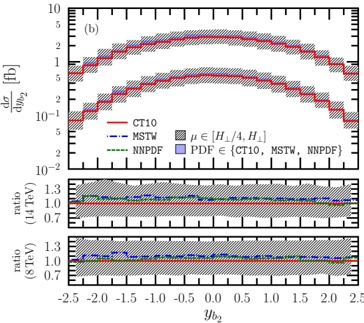

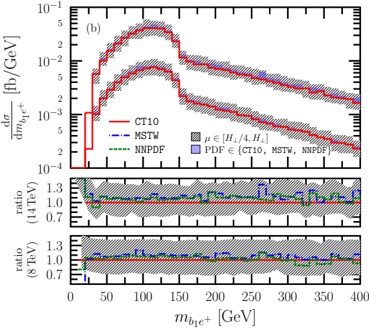

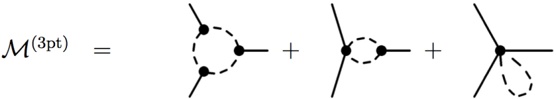

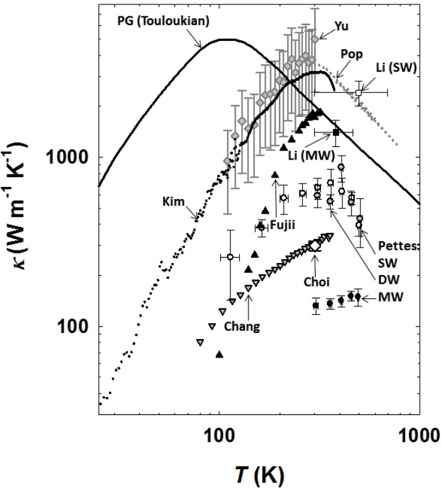

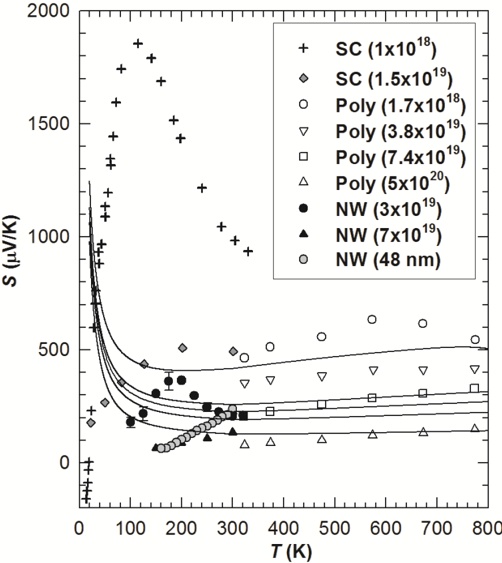

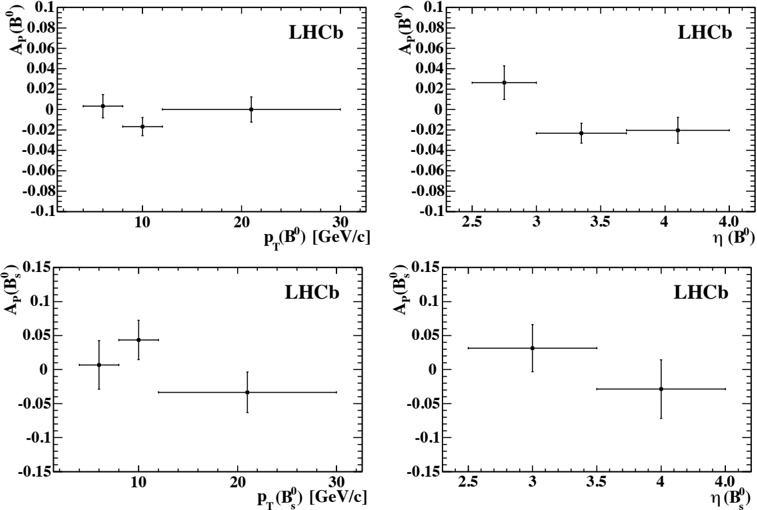

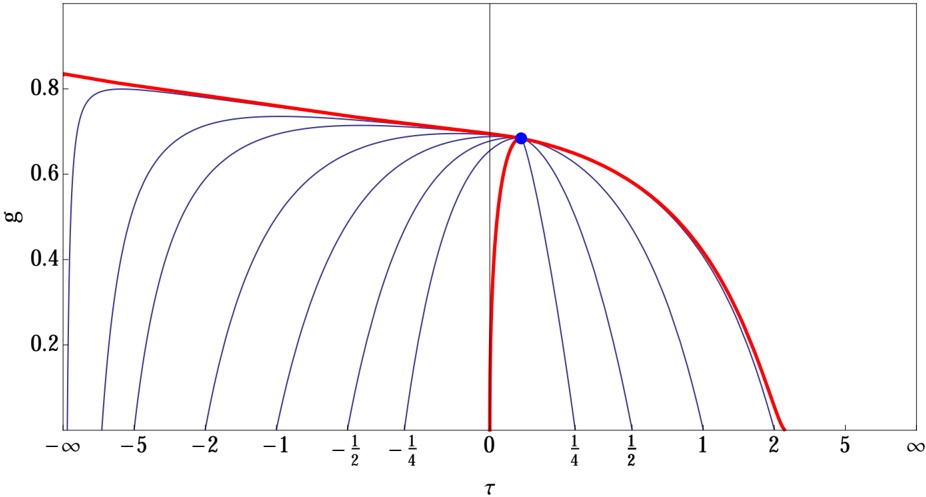

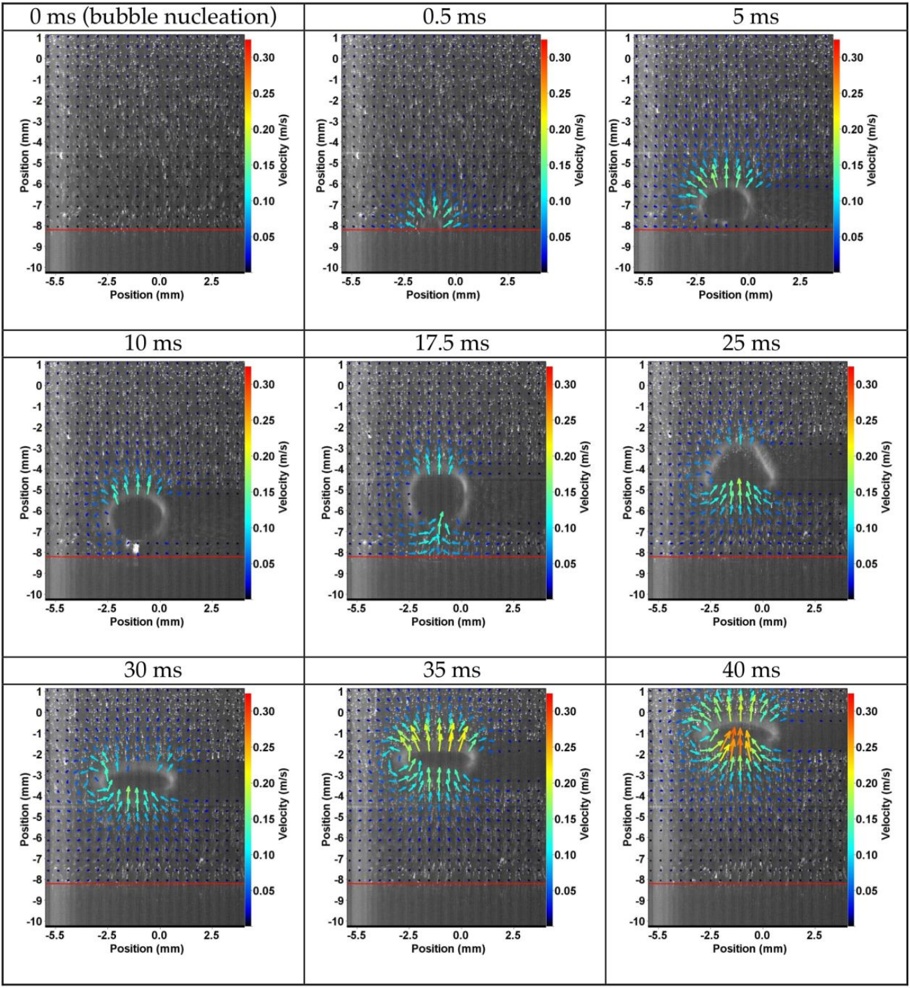

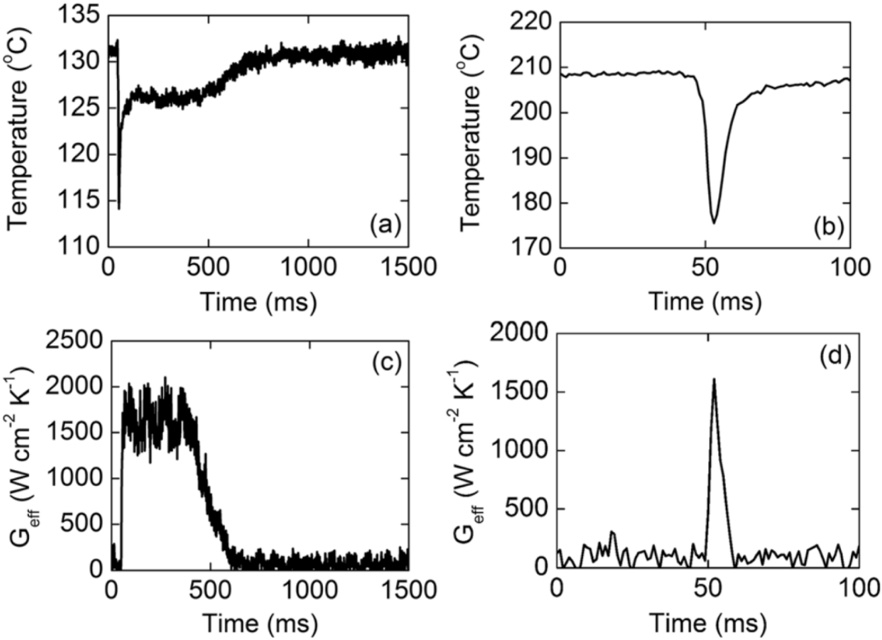

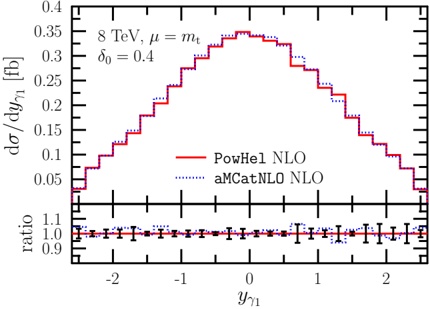

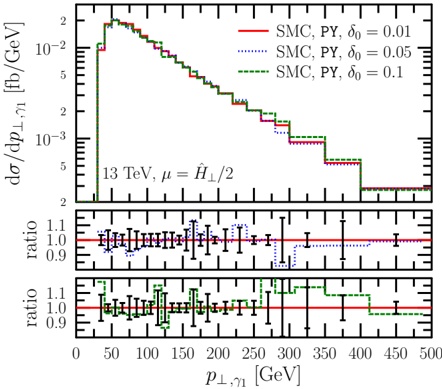

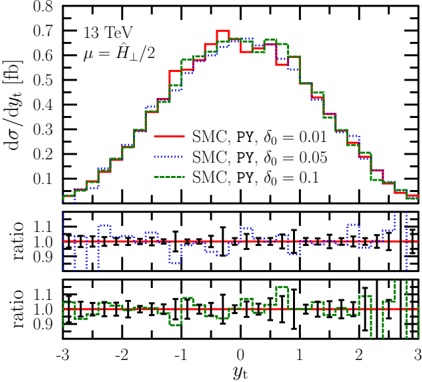

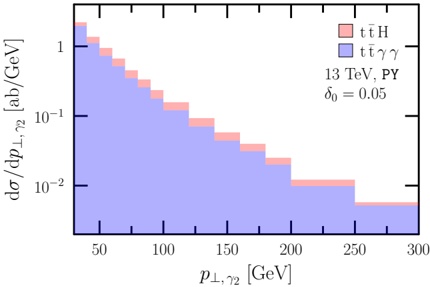

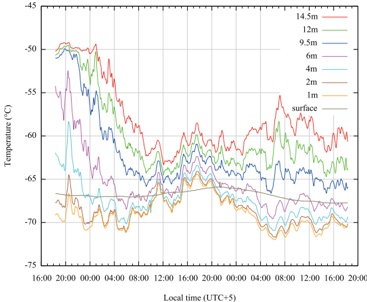

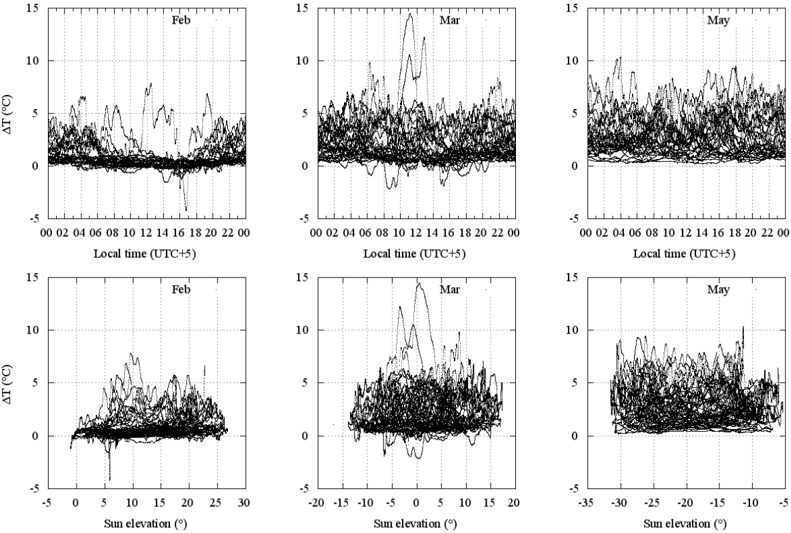

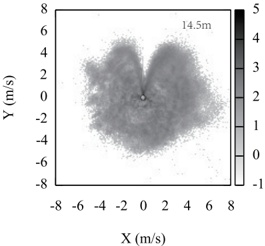

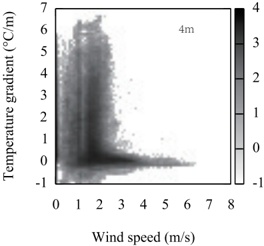

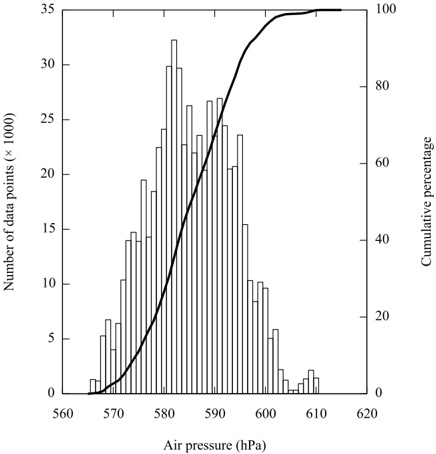

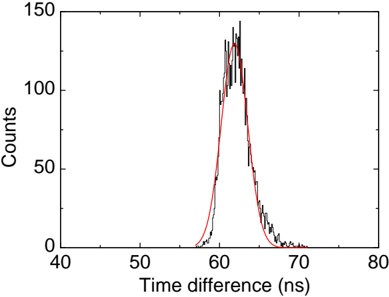

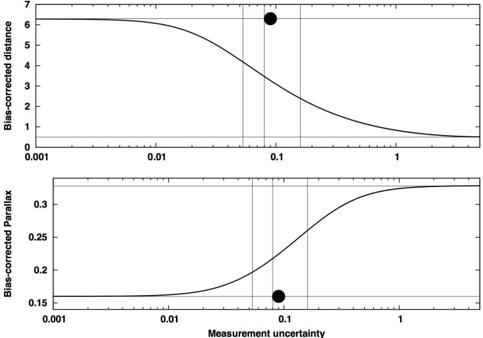

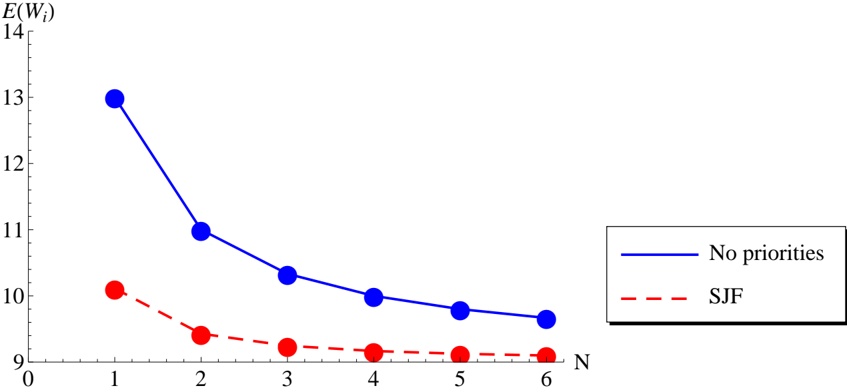

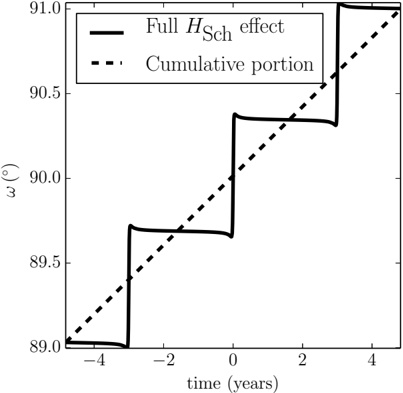

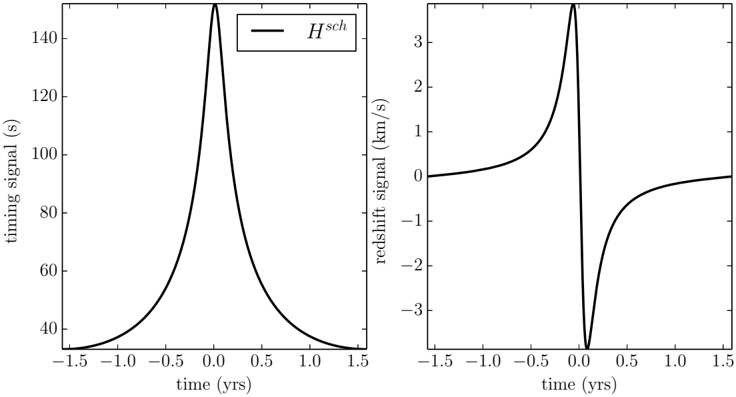

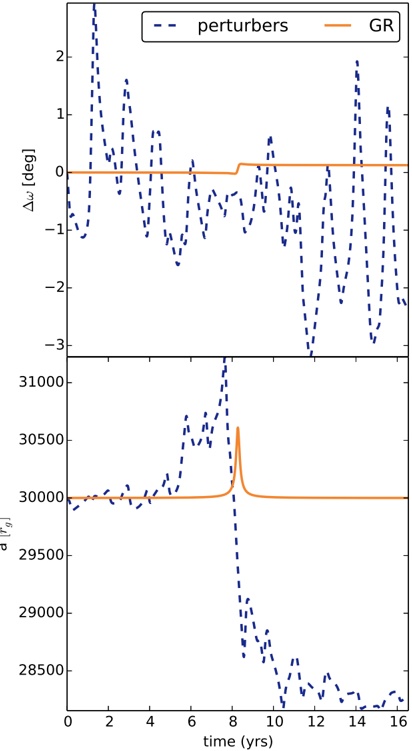

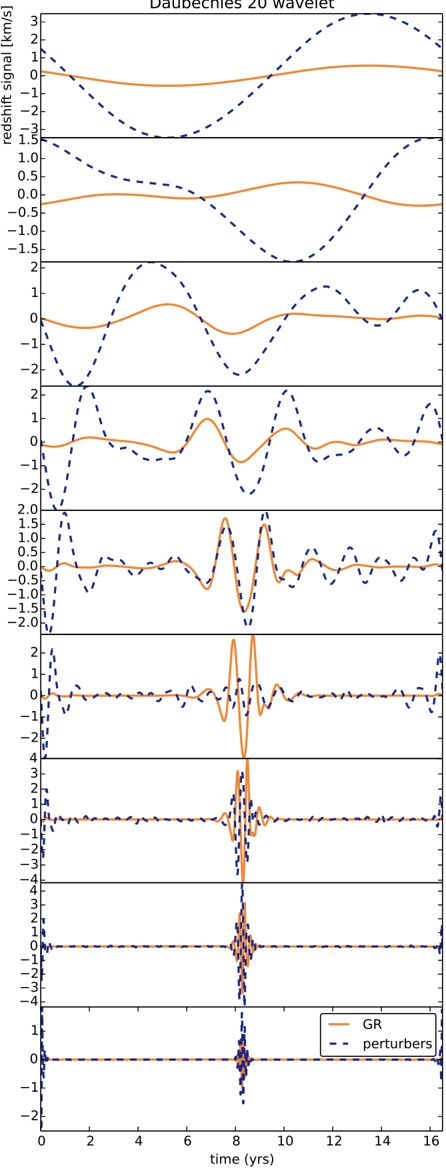

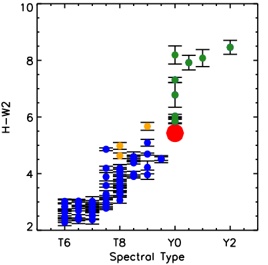

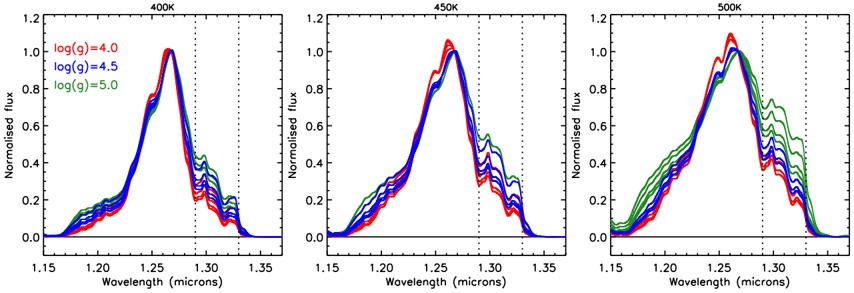

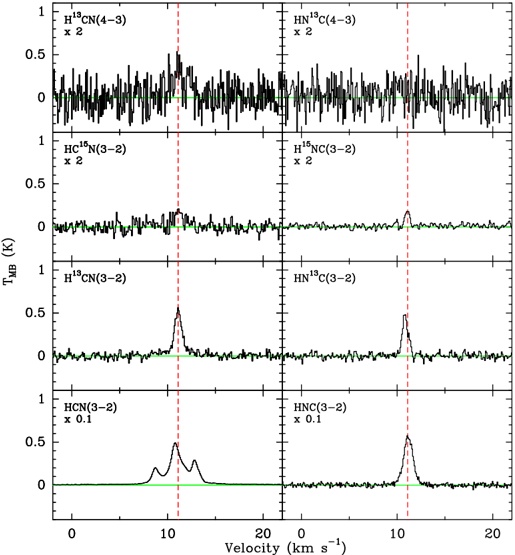

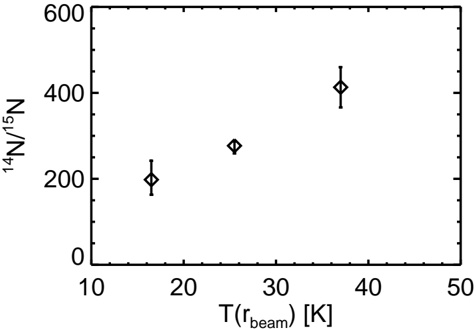

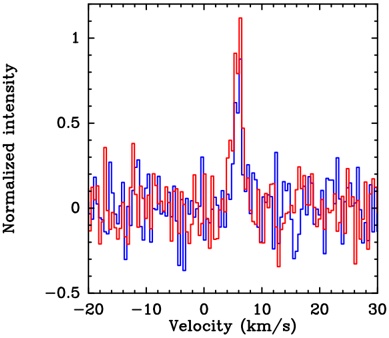

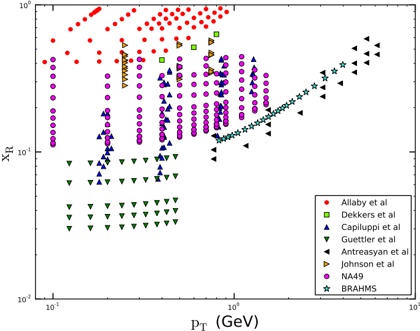

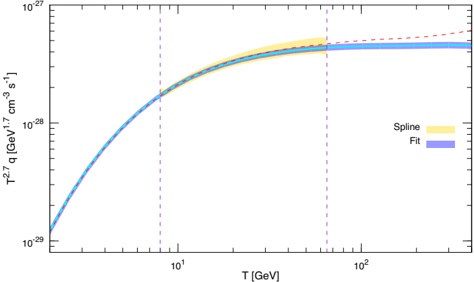

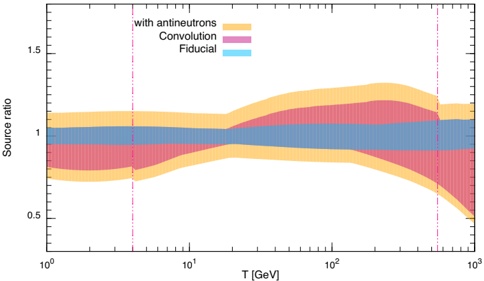

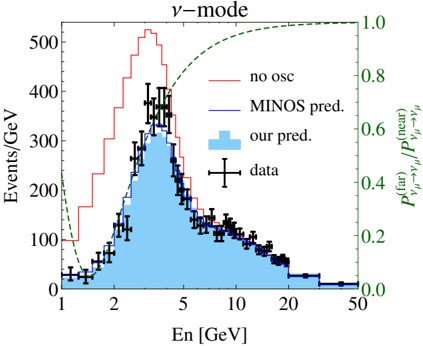

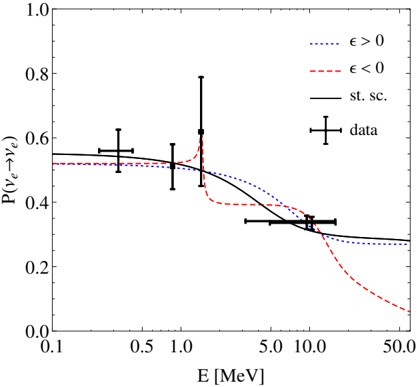

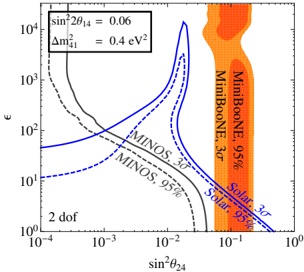

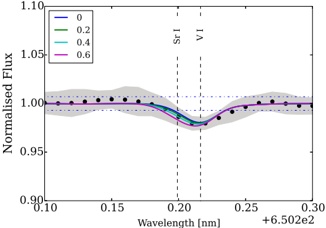

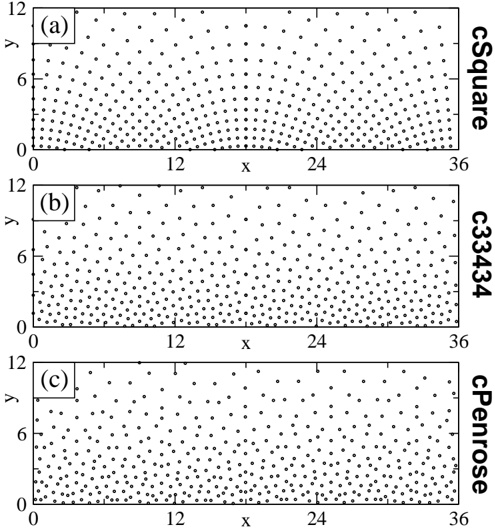

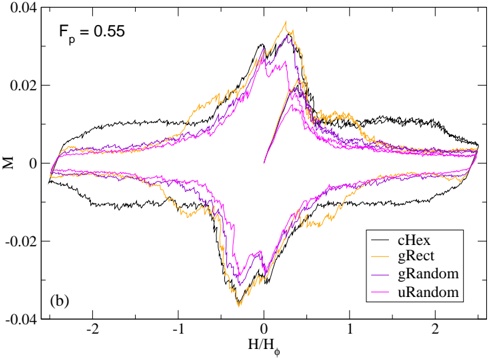

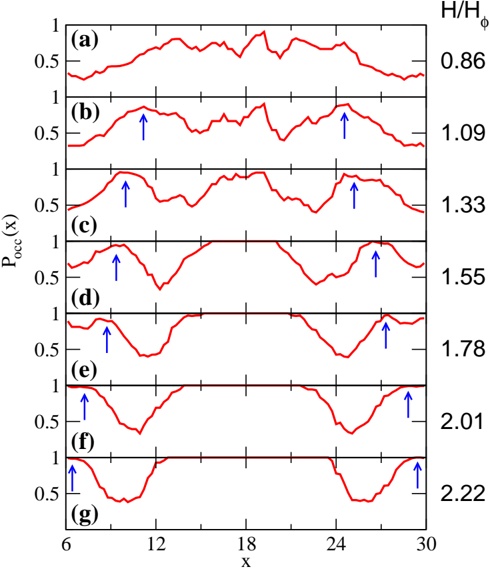

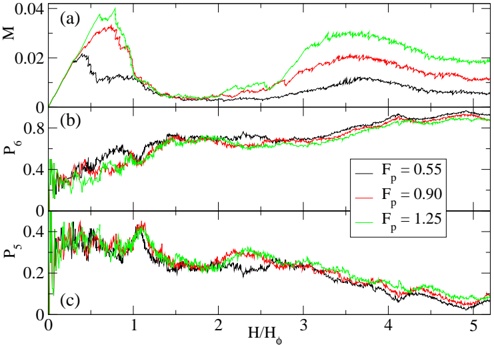

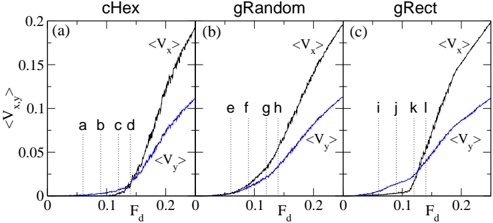

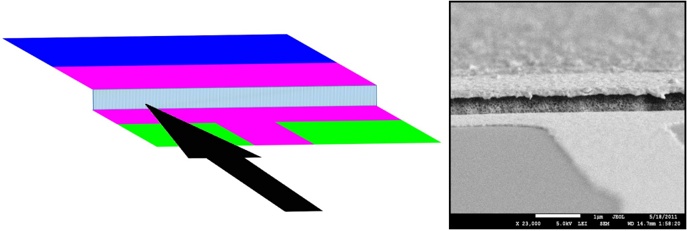

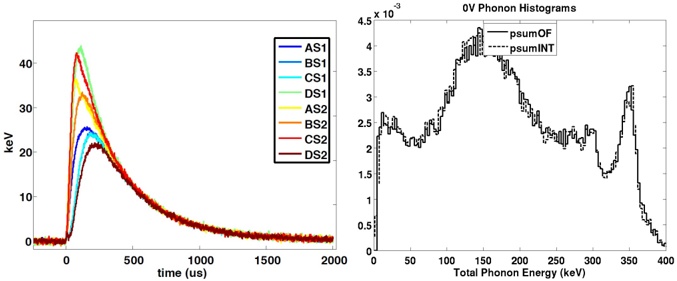

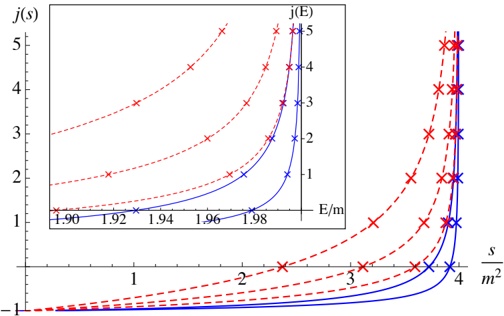

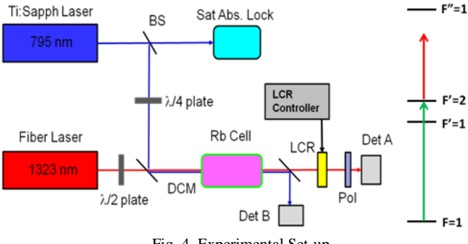

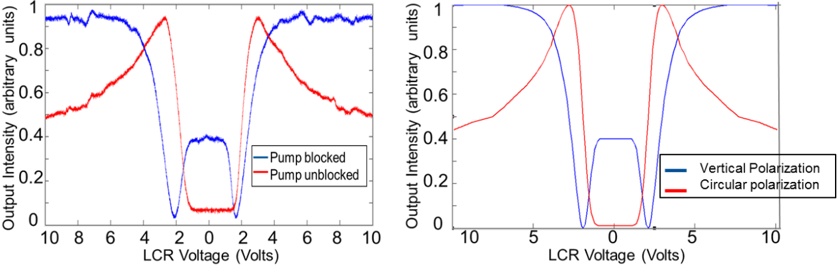

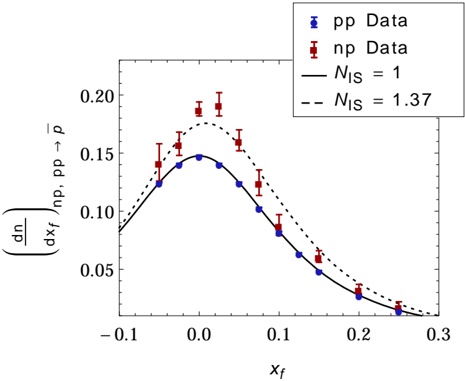

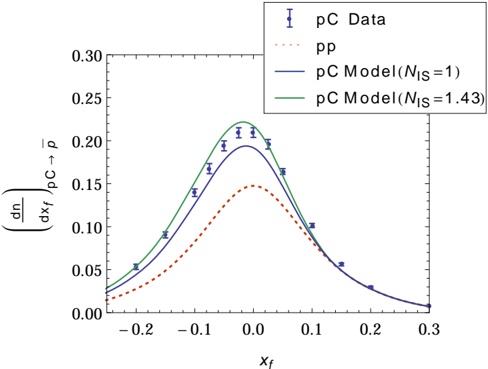

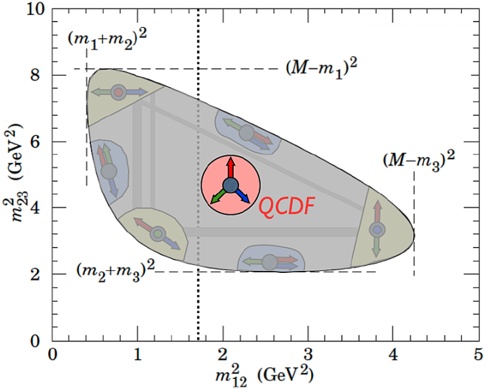

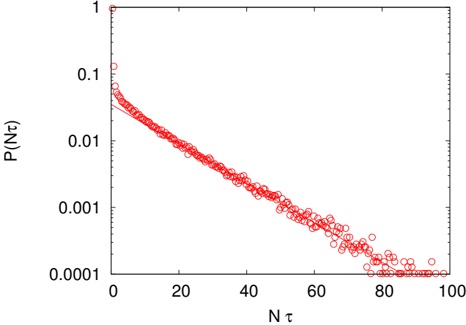

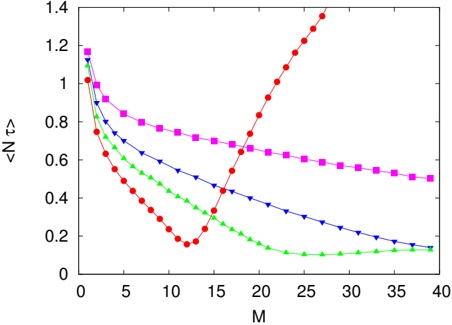

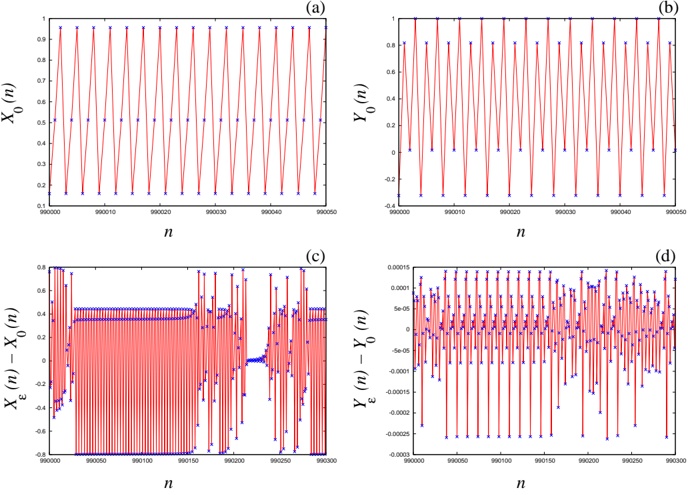

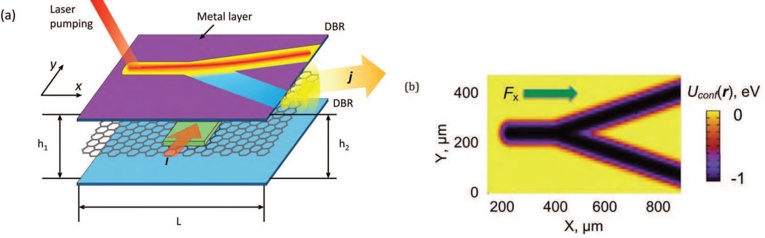

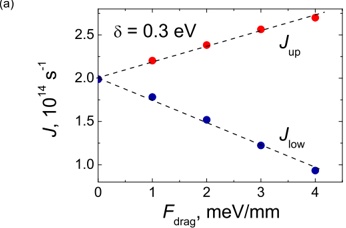

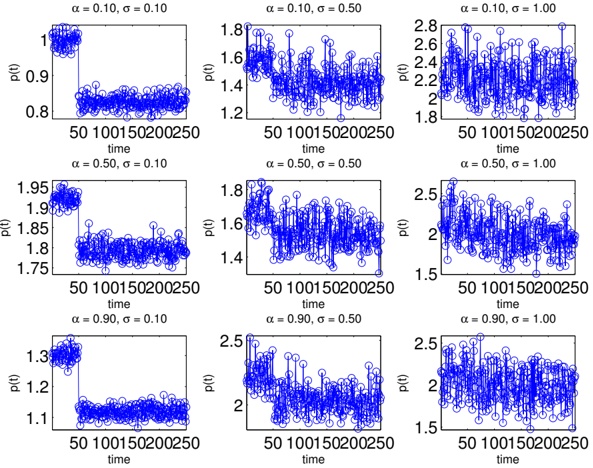

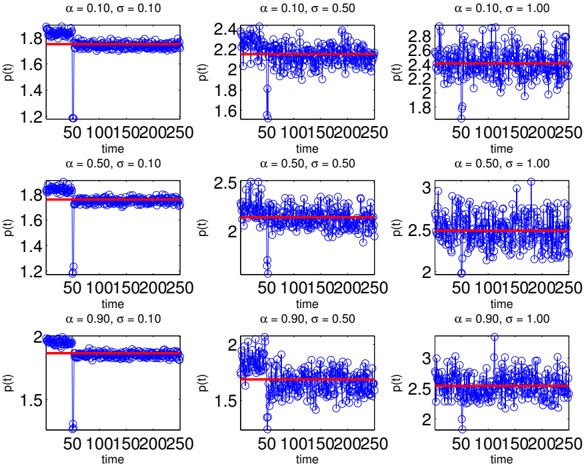

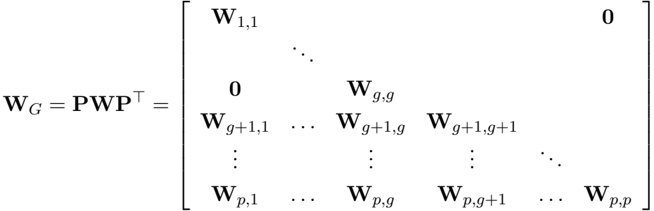

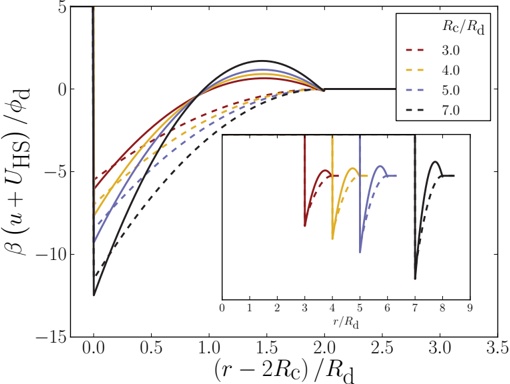

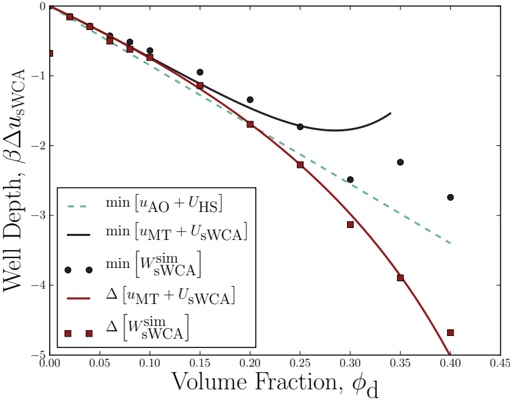

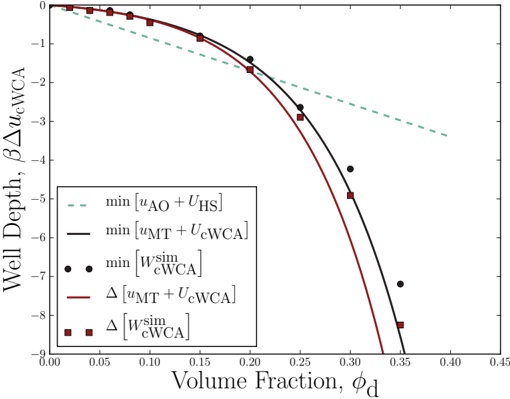

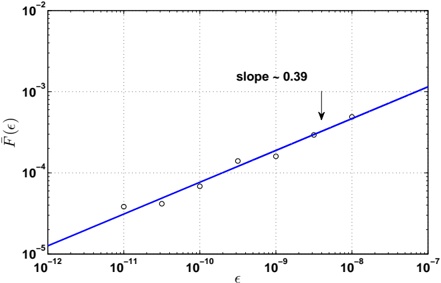

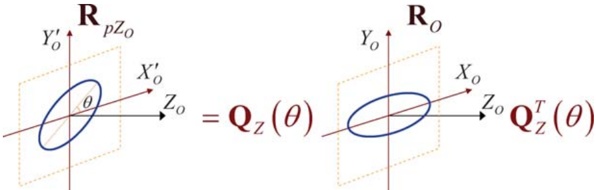

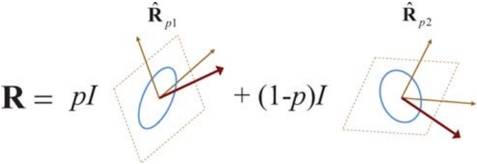

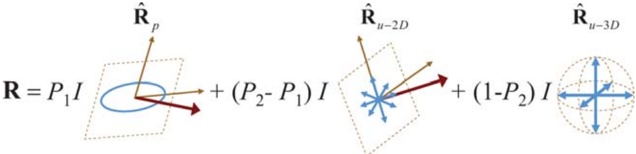

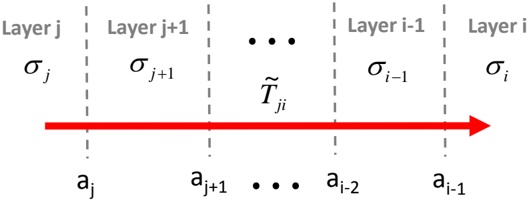

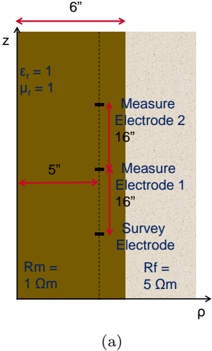

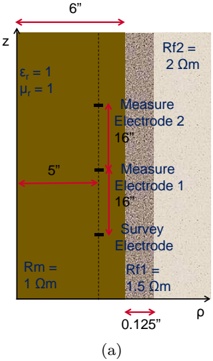

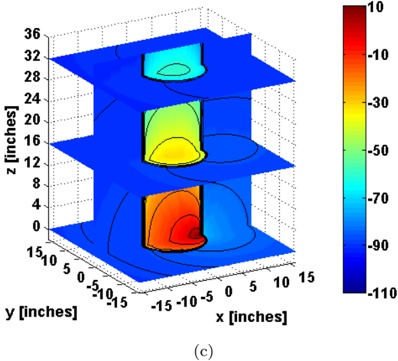

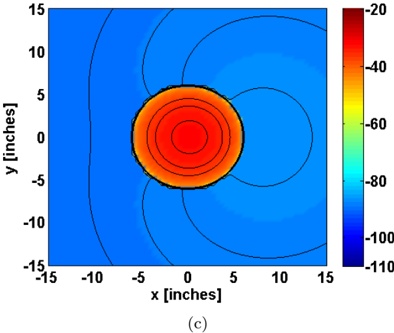

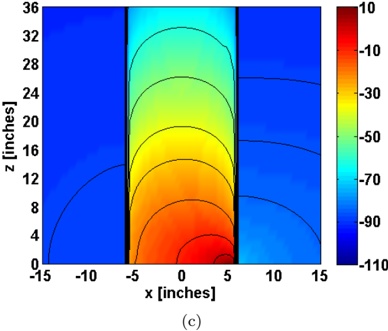

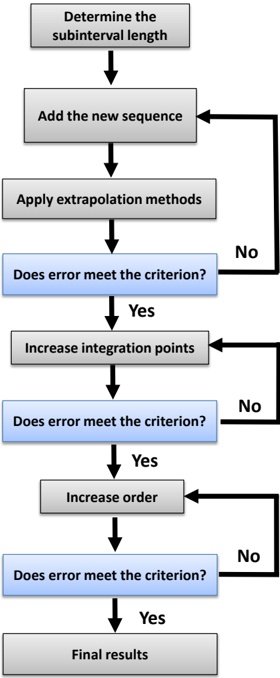

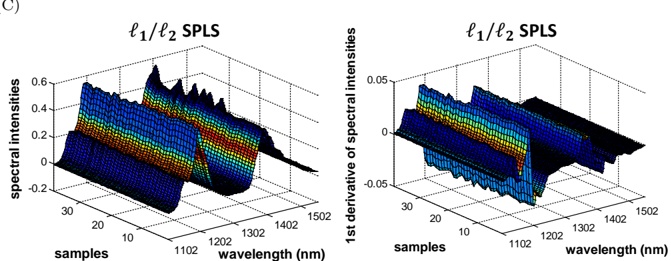

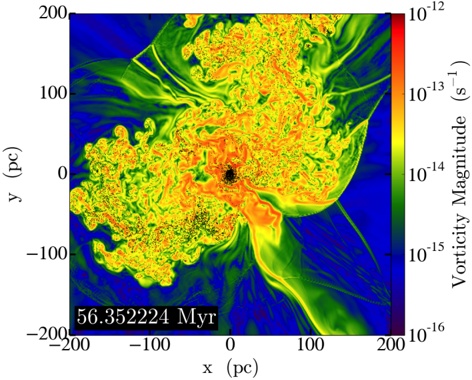

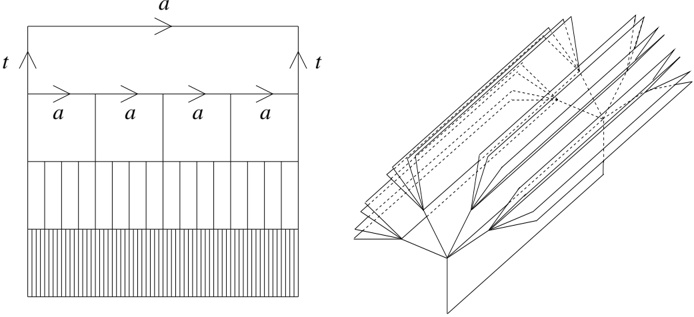

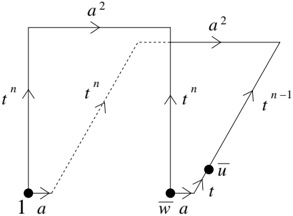

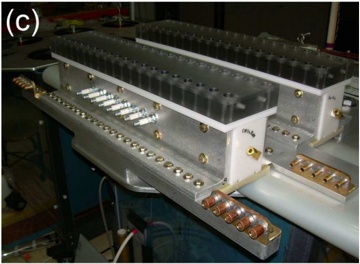

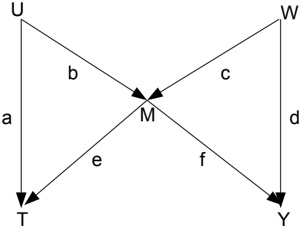

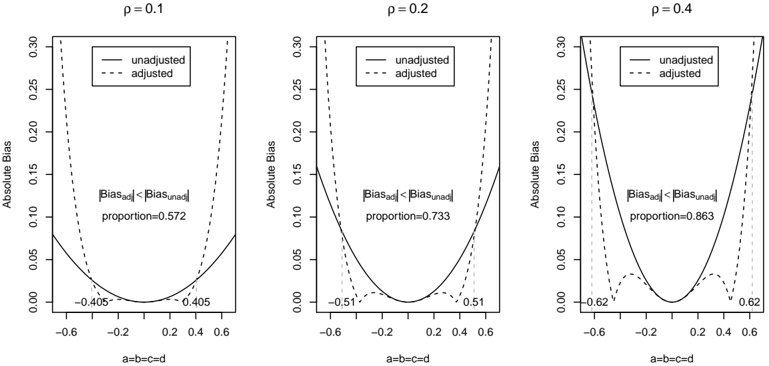

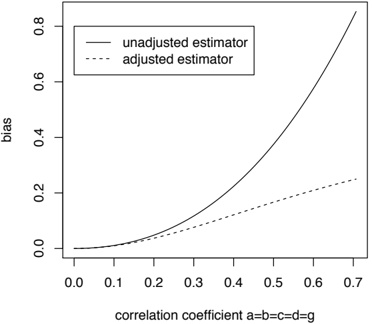

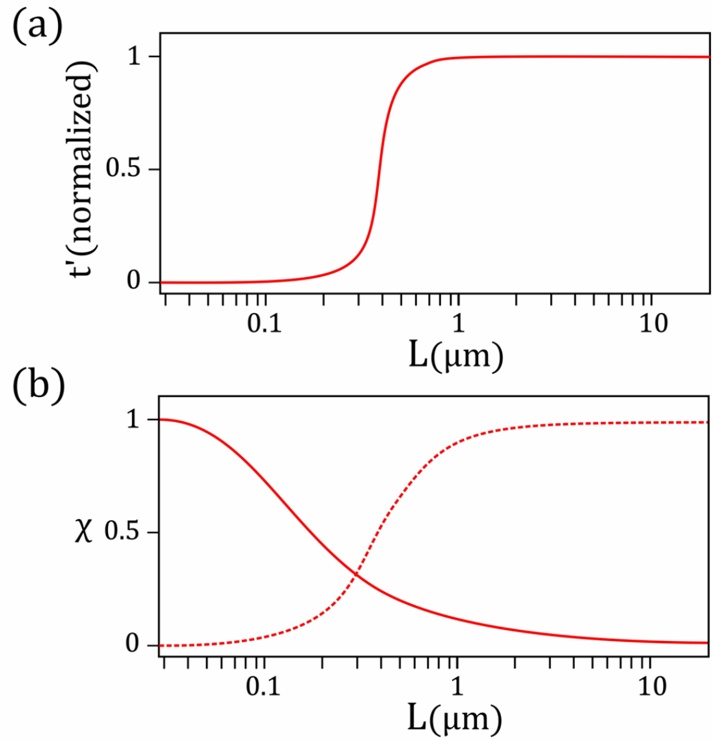

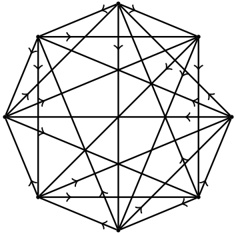

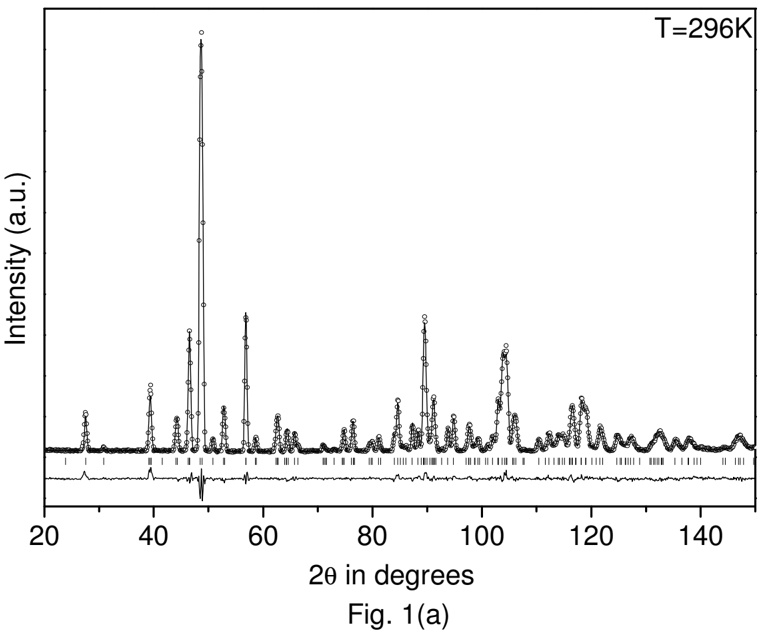

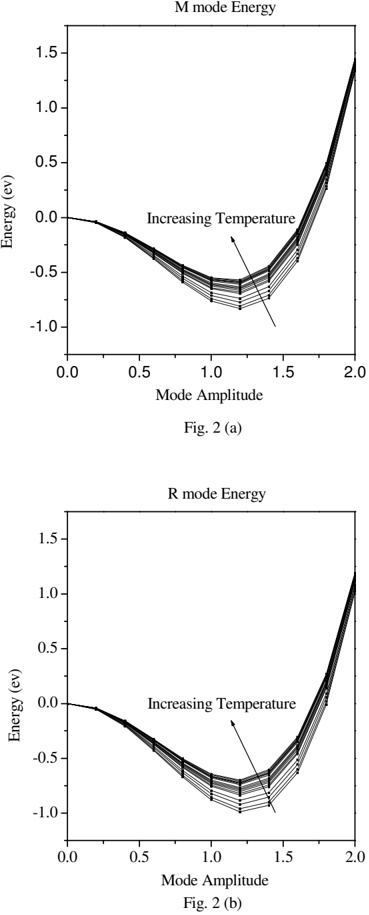

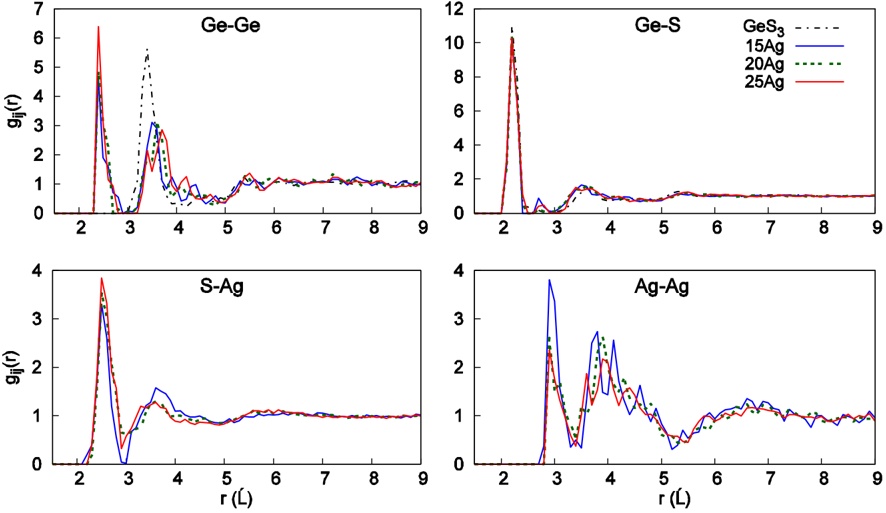

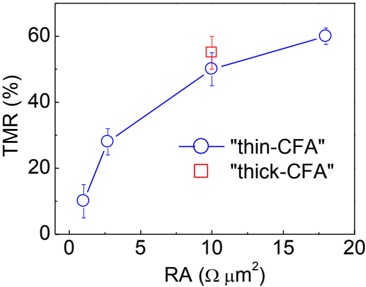

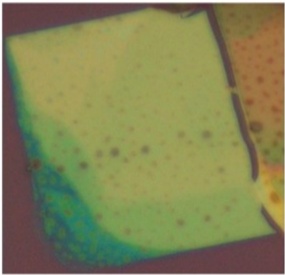

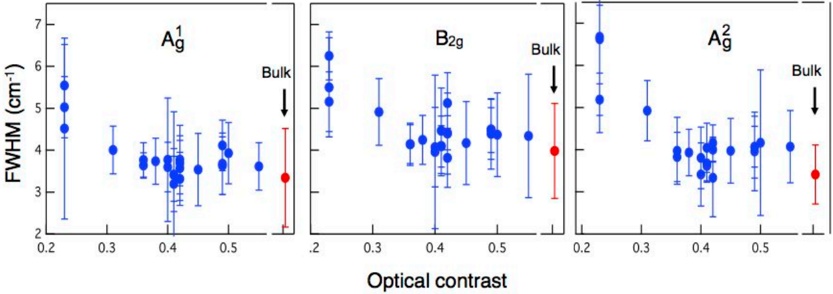

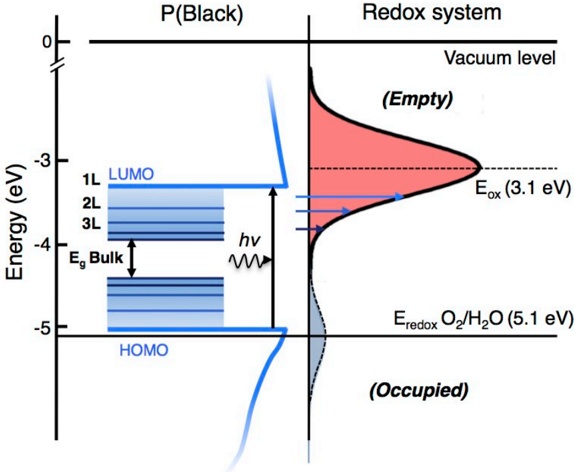

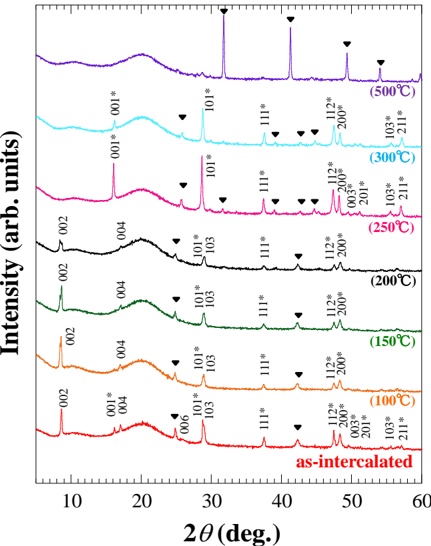

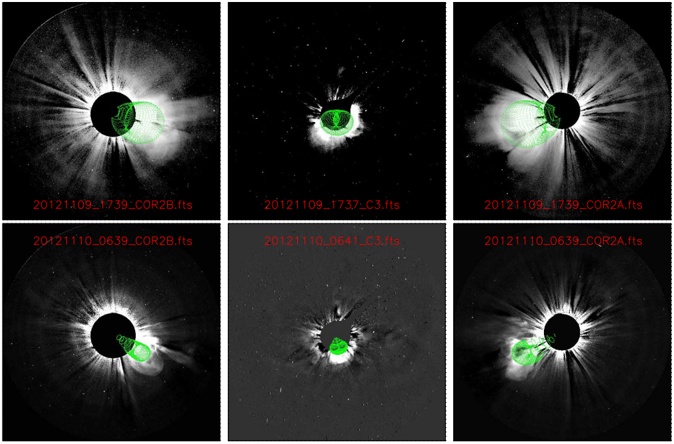

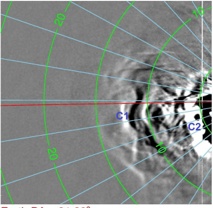

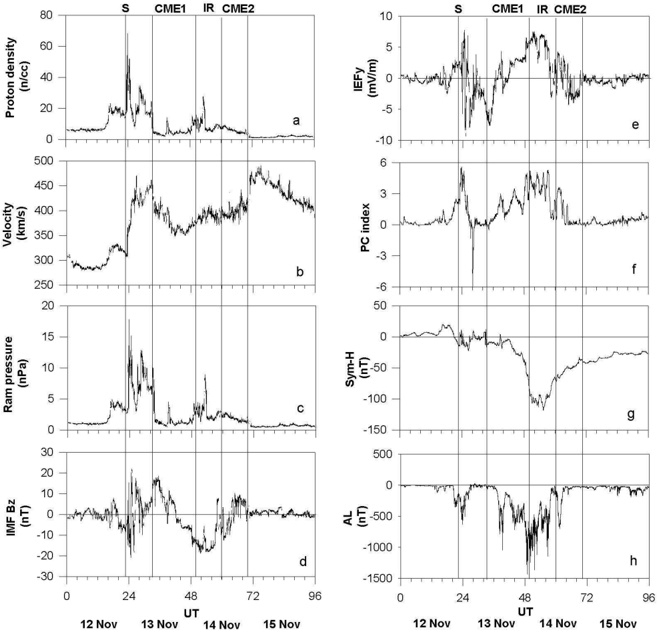

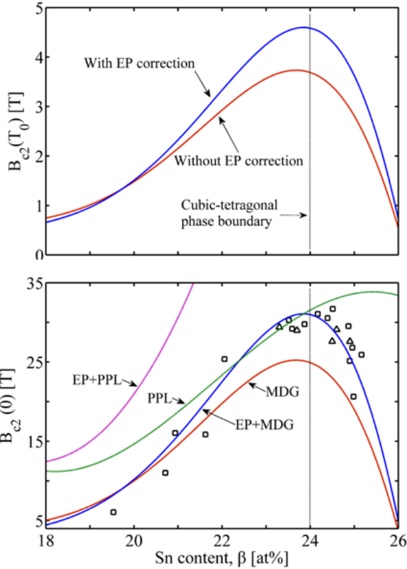

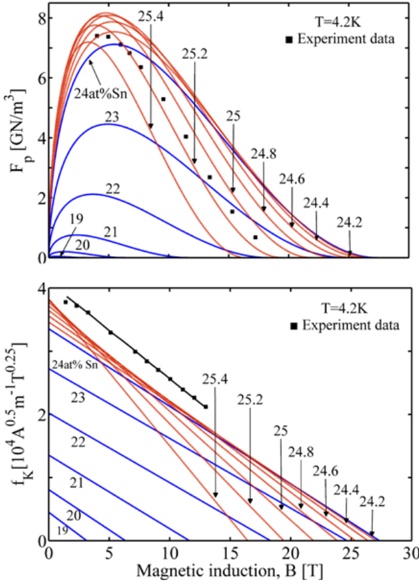

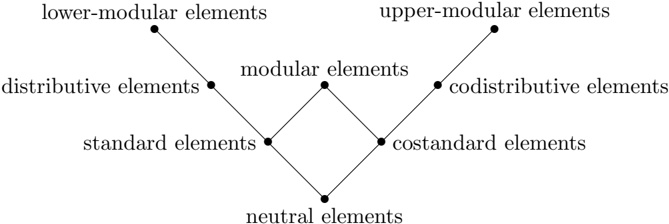

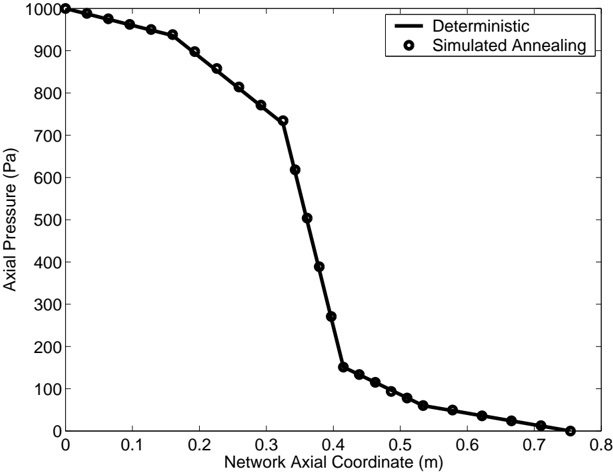

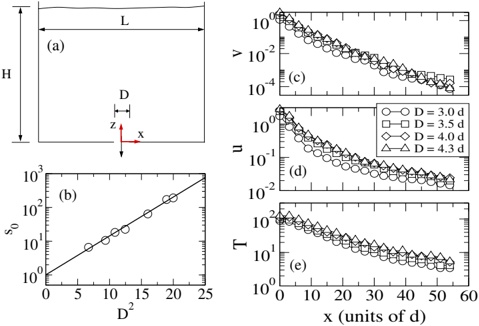

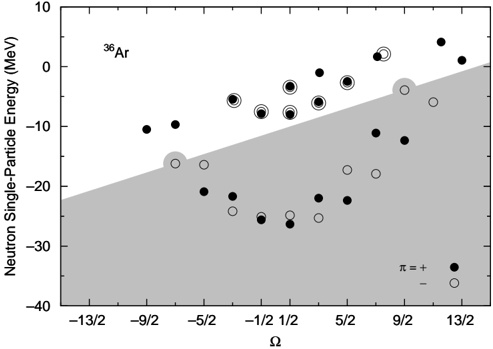

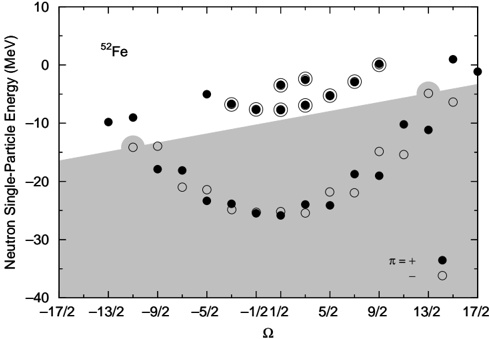

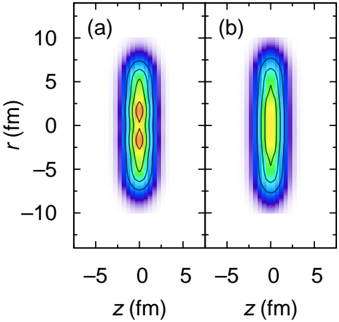

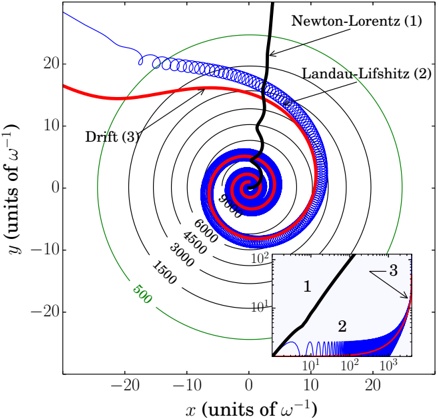

The percentage of stars with either no P µ or P µ ≥ 4% that we are able to classify as single or binary as a function of radius and V magnitude are shown in Figure 4. Lower classification percentages at the center of cluster are due to fiber separation requirements limiting the number of central stars we are able to observe in each pointing. The percentages decrease at larger radii in part because early in the survey we prioritized stars with color information and stars more than ∼ 18 ′ from the cluster center did not have color information until the inclusion of Y13 V I information in 2013. We are able to classify more than 75% of stars with V magnitude less than ∼ 15.5 as single or binary and this number jumps to 96% for stars within 18 ′ of the cluster center. Stars dimmer than this are observed less frequently because they require better observing conditions (clearer skies, dimmer moon, etc.) and longer exposures to meet our signal-to-noise requirements.

Table 2 Radial Velocity Summary Table

| ID W a | α (J2000) | δ (J2000) | V | V - I | N W | N C | RV | Std. Err. | e/i | P RV | P PM | Class b | γ RV | γ RVe | Comment |

|----------|-------------|-------------|-------|---------|-------|-------|----------|-------------|-------|--------|--------|-----------|--------|---------|-----------|

| 1001 | 19 41 18.71 | 40 11 42.9 | 12.69 | 1.41 | 3 | 20 | 6.045 | 3.4 | 23.88 | 90 | 19 | BM | 1.42 | 0.17 | SB1 |

| 1002 | 19 41 17.05 | 40 10 51.8 | 11.65 | 1.73 | 2 | 11 | 0.943 | 0.18 | 0.92 | 84 | 99 | SM | · · · | · · · | · · · |

| 1004 | 19 41 26.59 | 40 11 41.8 | 12.22 | 1.50 | 5 | 5 | 1.547 | 0.22 | 1.15 | 91 | 99 | SM | · · · | · · · | · · · |

| 1005 | 19 41 11.85 | 40 13 30.1 | · · · | · · · | 5 | 6 | - 38.297 | 0.19 | 1.02 | 0 | 87 | SN | · · · | · · · | · · · |

| 1006 | 19 41 17.76 | 40 9 15.9 | 12.83 | 1.23 | 5 | 13 | 1.473 | 0.96 | 6.3 | 94 | 99 | BM | 2.72 | 0.13 | SB1 |

| 1007 | 19 41 13.20 | 40 14 56.7 | · · · | · · · | 3 | 6 | 3.415 | 0.28 | 1.31 | 91 | 0 | SN | · · · | · · · | · · · |

| 1010 | 19 41 42.64 | 40 11 40.2 | 12.82 | 0.29 | 17 | 15 | 2.330 | 0.87 | 8.66 | 86 | 87 | BM | 1.07 | 0.35 | SB1 |

| 1011 | 19 41 44.98 | 40 12 50.3 | 11.80 | 0.59 | 2 | 6 | - 22.497 | 0.27 | 1.13 | 0 | 0 | SN | · · · | · · · | · · · |

| 1012 | 19 41 46.76 | 40 10 2.3 | 12.40 | 0.73 | 11 | 2 | 14.813 | 9.7 | 73.19 | 0 | 0 | BLN | · · · | · · · | · · · |

| 1013 | 19 41 44.81 | 40 8 1.9 | 11.97 | 0.62 | 6 | 9 | - 27.611 | 0.37 | 2.34 | 0 | 0 | SN | · · · | · · · | · · · |

a WOCS ID number. This number is based on V magnitude and radial distance from the cluster center. Full details can be found in Hole et al. (2009).

b See Section 4.5 for explanation of class codes.

(This table is available in its entirety in machine-readable and Virtual Observatory (VO) forms in the online journal. A portion is shown here for guidance regarding its form and content.)

Figure 4. Percentage of stars in our sample that have three or more RV observations and either no P µ information or a P µ ≥ 4% with respect to distance from the cluster center (left) and V magnitude (right).

## 4.4. RV Membership Probabilities

The RV membership probability of a given star, P RV , listed in Table 2 is calculated using the equation:

Table 3 Gaussian Fit Parameters for Cluster and Field RV Distributions

$$P _ { \text{RV} } ( v ) = \frac { F _ { \text{cluster} } ( v ) } { F _ { \text{field} } ( v ) + F _ { \text{cluster} } ( v ) }, \quad \quad ( 3 )$$