arxiv_id

stringlengths 11

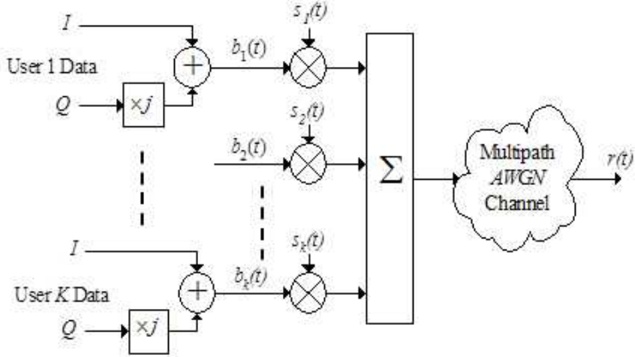

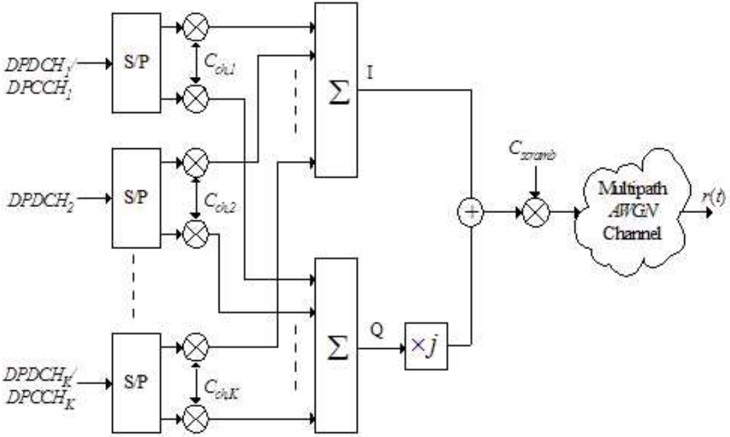

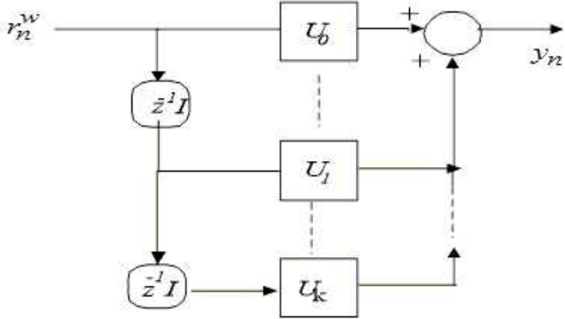

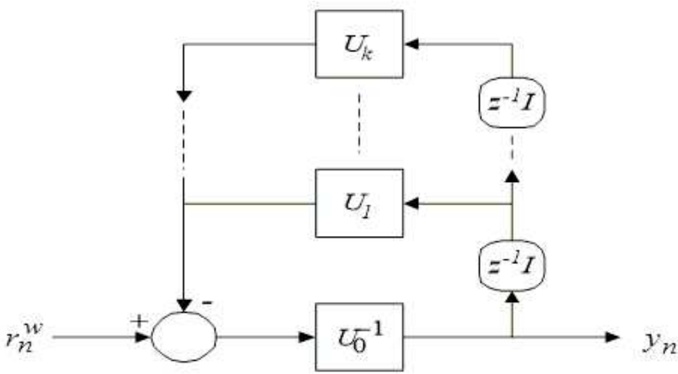

13

| markdown

stringlengths 2.09k

423k

| paper_doi

stringlengths 13

47

⌀ | paper_authors

sequencelengths 1

1.37k

| paper_published_date

stringdate 2014-06-03 19:36:41

2024-08-02 10:23:00

| paper_updated_date

stringdate 2014-06-27 01:00:59

2025-04-23 08:12:32

| categories

sequencelengths 1

7

| title

stringlengths 16

236

| summary

stringlengths 57

2.54k

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

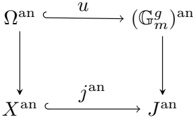

1408.0113v1 | ## Difference Krichever-Novikov operators

Gulnara S. Mauleshova and Andrey E. Mironov

## Abstract

In this paper we study commuting difference operators of rank two. We introduce an equation on potentials V ( n , W ) ( n ) of the difference operator L 4 = ( T + V ( n T ) -1 ) 2 + W n ( ) and some additional data. With the help of this equation we find the first examples of commuting difference operators of rank two corresponding to spectral curves of higher genus.

## 1 Introduction and main results

I.M. Krichever and S.P. Novikov [1], [2] discovered a remarkable class of solutions of soliton equations - algebro-geometric solutions of rank l > 1. This class is determined by the following condition: common eigenfunctions of auxiliary commuting ordinary differential or difference operators form a vector bundle of rank l over the spectral curve. Rank two solutions of the Kadomtsev-Petviashvili (KP) equation and 2D-Toda chain corresponding to the spectral curves of genus g = 1 were found in [1], [2]. To find higher rank solutions one has to find higher rank commuting operators and their appropriate deformations. The problem of classification of commuting differential and difference operators was solved in [2]-[4]; however, finding the operators themselves has remained an open problem. Moreover, no examples of commuting differential operators of rank l > 1 at g > 1 were known before the recent paper [5] (see also [6]).

In this paper we study commuting difference operators. We denote by L , L k s the operators of orders k = N -+ N + and s = M -+ M +

$$L _ { k } = \sum _ { j = N _ { - } } ^ { N _ { + } } u _ { j } ( n ) T ^ { j }, \ \ L _ { s } = \sum _ { j = M _ { - } } ^ { M _ { + } } v _ { j } ( n ) T ^ { j }, \ \ n \in \mathbb { Z },$$

where T is the shift operator. The condition of their commutativity is equivalent to a complicated system of nonlinear difference equations on the coefficients. These equations have been studied since the beginning of the 20th century (see [7]). An analogue of the Burchnall-Chaundy lemma [8] holds. Namely, if L L k s = L L s k , then there exists a nonzero polynomial F z, w ( ) such that F L , L ( k s ) = 0 [9]. The polynomial F defines the spectral curve

$$\Gamma = \{ ( z, w ) \in \mathbb { C } ^ { 2 } | F ( z, w ) = 0 \}.$$

The spectral curve parametrizes common eigenvalues, i.e. if

$$L _ { k } \psi = z \psi, \quad L _ { s } \psi = w \psi,$$

then ( z, w ) ∈ Γ . The dimension of the space of common eigenfunctions with the fixed eigenvalues is called the rank of the pair L , L k s

$$l = \dim \{ \psi \, \colon L _ { k } \psi = z \psi, \ \ L _ { s } \psi = w \psi \},$$

where the point ( z, w ) ∈ Γ is in general position. Thus the spectral curve and the rank are defined exactly the same way as in the case of the differential operators.

Before discussing difference operators we briefly discuss differential operators. The first important results relating to commuting differential operators of rank l > 1 were obtained by J. Dixmier [10] and V.G. Drinfel'd [11]. The operators of rank l with periodic coefficients were studied in [12]. Rank two operators at g = 1 were found by I.M. Krichever and S.P. Novikov [1]. These operators were studied in [13]-[20] (see also [21]-[24] for g = 2-4 , l = 2 3). , At g = 1 , l = 3 operators were found in [25]. Methods of [5] allow to construct and study higher rank operators at g > 1 [26]-[31].

The maximal commutative ring of difference operators containing L k and L s is isomorphic to the ring of meromorphic functions on an algebraic spectral curve Γ with poles q , . . . , q 1 m ∈ Γ (see [2]). Such operators are called m -points operators . We note that any ring of commuting differential operators is isomorphic to a ring of meromorphic functions on a spectral curve with a unique pole. The commuting difference operators of rank one were found by I.M. Krichever [9] and D. Mumford [32]. Eigenfunctions (Baker-Akhiezer functions) and coefficients of such operators can be found explicitly with the help of theta-functions of the Jacobi varieties of spectral curves. In the case of l > 1 eigenfunctions cannot be found explicitly. Finding such operators is still an open problem. Rank two one-point operators at g = 1 were found in [2], operators with polynomial coefficients among them were obtained in [33].

In this paper we consider one-point operators of rank two L , L 4 4 g +2 corresponding to the hyperelliptic spectral curve Γ

$$w ^ { 2 } = F _ { g } ( z ) = z ^ { 2 g + 1 } + c _ { 2 g } z ^ { 2 g } + c _ { 2 g - 1 } z ^ { 2 g - 1 } + \dots + c _ { 0 },$$

herewith

$$L _ { 4 } = \sum _ { i = - 2 } ^ { 2 } u _ { i } ( n ) T ^ { i }, \quad L _ { 4 g + 2 } = \sum _ { i = - ( 2 g + 1 ) } ^ { 2 g + 1 } v _ { i } ( n ) T ^ { i }, \quad u _ { 2 } = v _ { 2 g + 1 } = 1, \quad \ ( 2 ) \\ _ { - } \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot _ { - } \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot _ { - } \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot _ { - } \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot _ { - } \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot _ { - } \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot$$

$$L _ { 4 } \psi = z \psi, \quad L _ { 4 g + 2 } \psi = w \psi, \quad \psi = \psi ( n, P ), \quad P = ( z, w ) \in \Gamma. \quad \ \ ( 3 )$$

Common eigenfunctions of L 4 and L 4 g +2 satisfy the equation

$$\psi ( n + 1, P ) = \chi _ { 1 } ( n, P ) \psi ( n - 1, P ) + \chi _ { 2 } ( n, P ) \psi ( n, P ),$$

where χ 1 ( n, P ) and χ 2 ( n, P ) are rational functions on Γ having 2 g simple poles, depending on n (see [2]). The function χ 2 ( n, P ) additionally has a simple pole at q = ∞ . To

find L 4 and L 4 g +2 it is sufficient to find χ 1 and χ . 2 Let σ be the holomorphic involution on Γ , σ z, w ( ) = σ z, ( -w . ) The main results of this paper are Theorems 1-4.

## Theorem 1 If

$$\chi _ { 1 } ( n, P ) = \chi _ { 1 } ( n, \sigma ( P ) ), \quad \chi _ { 2 } ( n, P ) = - \chi _ { 2 } ( n, \sigma ( P ) ),$$

then L 4 has the form

$$L _ { 4 } = ( T + V _ { n } T ^ { - 1 } ) ^ { 2 } + W _ { n },$$

where

$$\chi _ { 1 } = - V _ { n } \frac { Q _ { n + 1 } } { Q _ { n } }, \quad \chi _ { 2 } = \frac { w } { Q _ { n } }, \quad Q _ { n } ( z ) = z ^ { g } + \alpha _ { g - 1 } ( n ) z ^ { g - 1 } + \dots + \alpha _ { 0 } ( n ). \quad ( 7 )$$

Functions V , W , Q n n n satisfy

$$F _ { g } ( z ) = Q _ { n - 1 } Q _ { n + 1 } V _ { n } + Q _ { n } Q _ { n + 2 } V _ { n + 1 } + Q _ { n } Q _ { n + 1 } ( z - V _ { n } - V _ { n + 1 } - W _ { n } ).$$

In Theorem 1 and further we use the notations V n = V ( n , W ) n = W n ( ). It is a remarkable fact that (8) can be linearized. Namely, if we replace n → n +1 and take the difference with (8), then the result can be divided by Q n +1 ( z . ) Finally we obtain the linear equation on Q n ( z ).

Corollary 1 Functions Q n ( z , V ) n , W n satisfy

$$Q _ { n - 1 } V _ { n } + Q _ { n } ( z - V _ { n } - V _ { n + 1 } - W _ { n } ) - Q _ { n + 2 } ( z - V _ { n + 1 } - V _ { n + 2 } - W _ { n + 1 } ) - Q _ { n + 3 } V _ { n + 2 } = 0. \ ( 9 )$$

At g = 1, the equation (8) allows us to express V , W n n via a functional parameter γ . n

Corollary 2 The operator L 4 = ( T + V T n -1 ) 2 + W , n where

$$V _ { n } = \frac { F _ { 1 } ( \gamma _ { n } ) } { ( \gamma _ { n } - \gamma _ { n - 1 } ) ( \gamma _ { n } - \gamma _ { n + 1 } ) }, \quad W _ { n } = - c _ { 2 } - \gamma _ { n } - \gamma _ { n + 1 },$$

commutes with

$$L _ { 6 } = T ^ { 3 } + ( V _ { n } + V _ { n + 1 } + V _ { n + 2 } + W _ { n } - \gamma _ { n + 2 } ) T +$$

$$\begin{matrix} + V _ { n } ( V _ { n - 1 } + V _ { n } + V _ { n + 1 } + W _ { n } - \gamma _ { n - 1 } ) T ^ { - 1 } + V _ { n - 2 } V _ { n - 1 } V _ { n } T ^ { - 3 }. \\ \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \cdot \end{matrix}$$

The spectral curve of L , L 4 6 is w 2 = F 1 ( z . )

In the theory of commuting ordinary differential operators there are equations which are similar to (8), (9). Let us compare (8), (9) with their smooth analogues. First, we consider the one-dimensional finite-gap Schr¨dinger operator o L 2 = -∂ 2 x + V ( x ) commuting with a differential operator L 2 g +1 of order 2 g +1. The theory of such operators is

closely related to the theory of periodic and quasiperiodic solutions of the Korteweg-de Vries equation (see [34]-[36]). Denote by ψ a common eigenfunction

$$( - \partial _ { x } ^ { 2 } + \mathcal { V } ( x ) ) \psi = z \psi, \quad \mathcal { L } _ { 2 g + 1 } \psi = w \psi.$$

The point P = ( z, w ) belongs to the spectral curve (1). Function ψ x, P ( ) satisfies

$$\psi ^ { \prime } ( x, P ) = i \chi _ { 0 } ( x, P ) \psi ( x, P ),$$

where

$$\chi _ { 0 } = \frac { \mathcal { Q } _ { x } } { 2 i \mathcal { Q } } + \frac { w } { \mathcal { Q } }, \quad \mathcal { Q } = z ^ { g } + \alpha _ { g - 1 } ( x ) z ^ { g - 1 } + \dots + \alpha _ { 0 } ( x ).$$

Polynomial Q satisfies the equation

$$4 F _ { g } ( z ) = 4 ( z - \mathcal { V } ) \mathcal { Q } ^ { 2 } - ( \mathcal { Q } _ { x } ) ^ { 2 } + 2 \mathcal { Q } \mathcal { Q } _ { x x },$$

which is linearized as well as (8) (see [37], [38])

$$\mathcal { Q } _ { x x x } - 4 \mathcal { Q } _ { x } ( \mathcal { V } - z ) - 2 \mathcal { V } _ { x } \mathcal { Q } = 0.$$

Equations (8), (9) are analogues of the last two.

Let us consider one more example. We denote by L 4 , L 4 g +2 rank two commuting differential operators with the spectral curve (1). The common eigenfunctions of L 4 and L 4 g +2 satisfy

$$\psi ^ { ^ { \prime \prime } } = \chi _ { 1 } ( x, P ) \psi ^ { \prime } + \chi _ { 0 } ( x, P ) \psi.$$

In [5] it was proved that L 4 is self-adjoint if and only if χ 1 ( x, P ) = χ 1 ( x, σ ( P )) , herewith

$$\mathcal { L } _ { 4 } = ( \partial _ { x } ^ { 2 } + \mathcal { V } ( x ) ) ^ { 2 } + \mathcal { W } ( x ),$$

$$\chi _ { 0 } = - \frac { 1 } { 2 } \frac { \mathcal { Q } _ { x x } } { \mathcal { Q } } + \frac { w } { \mathcal { Q } } - \mathcal { V }, \quad \chi _ { 1 } = \frac { \mathcal { Q } _ { x } } { \mathcal { Q } }, \quad \mathcal { Q } = z ^ { g } + \alpha _ { g - 1 } ( x ) z ^ { g - 1 } + \dots + \alpha _ { 0 } ( x ),$$

polynomial Q satisfies

$$4 F _ { g } ( z ) = 4 ( z - \mathcal { W } ) \mathcal { Q } ^ { 2 } - 4 \mathcal { V } ( \mathcal { Q } _ { x } ) ^ { 2 } + \mathcal { Q } _ { x x } ^ { 2 } - 2 \mathcal { Q } _ { x } \mathcal { Q } _ { x x x } + 2 \mathcal { Q } ( 2 \mathcal { V } _ { x } \mathcal { Q } _ { x } + 4 \mathcal { V } \mathcal { Q } _ { x x } + \mathcal { Q } _ { x x x x } ), \ ( 1 1 )$$

and also satisfies

$$\partial _ { x } ^ { 5 } \mathcal { Q } + 4 \mathcal { V } \mathcal { Q } _ { x x x } + 2 \mathcal { Q } _ { x } ( 2 z - 2 \mathcal { W } - \mathcal { V } _ { x x } ) + 6 \mathcal { V } _ { x } \mathcal { Q } _ { x x } - 2 \mathcal { Q } \mathcal { W } _ { x } = 0.$$

Equations (8), (9) are discrete analogues of (11), (12).

Theorem 1 allows us to construct the examples.

## Theorem 2 The operator

/negationslash

$$L _ { 4 } ^ { \mathfrak { f } } = ( T + ( r _ { 3 } n ^ { 3 } + r _ { 2 } n ^ { 2 } + r _ { 1 } n + r _ { 0 } ) T ^ { - 1 } ) ^ { 2 } + g ( g + 1 ) r _ { 3 } n, \quad r _ { 3 } \neq 0$$

commutes with a difference operator L /sharp 4 g +2 .

Theorem 3 The operator

/negationslash

$$L _ { 4 } ^ { \ < } = ( T + ( r _ { 1 } a ^ { n } + r _ { 0 } ) T ^ { - 1 } ) ^ { 2 } + r _ { 1 } ( a ^ { 2 g + 1 } - a ^ { g + 1 } - a ^ { g } + 1 ) a ^ { n - g }, \quad r _ { 1 }, a \neq 0,$$

/negationslash where a 2 g +1 -a g +1 -a g +1 = 0 , commutes with a difference operator L /check 4 g +2 .

## Theorem 4 The operator

/negationslash

$$L _ { 4 } ^ { \ddagger } = ( T + ( r _ { 1 } \cos ( n ) + r _ { 0 } ) T ^ { - 1 } ) ^ { 2 } - 4 r _ { 1 } \sin ( \frac { g } { 2 } ) \sin ( \frac { g + 1 } { 2 } ) \cos ( n + \frac { 1 } { 2 } ), \quad r _ { 1 } \neq 0$$

commutes with a difference operator L /natural 4 g +2 .

In Section 2 we recall the Krichever-Novikov equations on Tyurin parameters.

In Section 3 we prove Theorems 1-4 and consider examples.

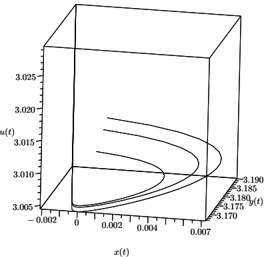

In Appendix we consider the differential-difference system on V n ( ) t , W t n ( )

$$\dot { V } _ { n } = V _ { n } ( W _ { n - 1 } - W _ { n } + V _ { n - 1 } - V _ { n + 1 } ),$$

$$\dot { W } _ { n } = ( W _ { n } - W _ { n - 1 } ) V _ { n } + ( W _ { n + 1 } - W _ { n } ) V _ { n + 1 }.$$

$$\mathcal { W } _ { n } - W _ { n - 1 } ) V _ { n } + \underset { \dots } { ( W _ { n + 1 } - W _ { n } ) V _ { n + 1 } }. \underset { \dots } { ( W _ { n + 1 } - W _ { n } ) V _ { n + 1 } }. \underset { \dots } { ( 1 4 ) }$$

From (13), (14) it follows that ϕ n ( ), where t e ϕ n ( ) t = V n ( ), satisfies the generalized Toda t chain

$$\ddot { \varphi } _ { n } = e ^ { \varphi _ { n - 2 } + \varphi _ { n - 1 } } - e ^ { \varphi _ { n - 1 } + \varphi _ { n } } + e ^ { \varphi _ { n + 1 } + \varphi _ { n + 2 } } - e ^ { \varphi _ { n + 1 } + \varphi _ { n } }.$$

From (13), (14) it follows also that

$$[ L _ { 4 }, \partial _ { t } - V _ { n - 1 } ( t ) V _ { n } ( t ) T ^ { - 2 } ] = 0,$$

where L 4 = ( T + V n ( ) t T -1 ) 2 + W t . n ( ) Following [1], [2] we call the solution V n ( ) t , W n ( ) t of (13), (14) the solution of rank two , if additionally [ L , L 4 4 g +2 ] = 0 for some difference operator L 4 g +2 . In the case of rank two solutions an evolution equation on Q n ( ) t is obtained in Theorem 5. At g = 1 this equation is reduced to a discrete analogue of the Krichever-Novikov equation, which appeared in the theory of rank two solutions of KP.

## 2 Discrete dynamics of the Tyurin parameters

As mentioned above, in the case of rank one operators the eigenfunctions can be found explicitly in terms of theta-functions of the Jacobi varieties of spectral curves. Let us consider the simplest example. Let Γ be an elliptic curve Γ = C / { Z + τ Z } , τ ∈ C , Im τ > 0 , and θ z ( ) the theta-function θ z ( ) = ∑ n ∈ Z exp( πin τ 2 + 2 πinz . ) The Baker-Akhiezer function has the form

$$\psi ( n, z ) = \frac { \theta ( z + c + n h ) } { \theta ( z ) } \left ( \frac { \theta ( z - h ) } { \theta ( z ) } \right ) ^ { n }, \quad c, h \notin \{ \mathbb { Z } + \tau \mathbb { Z } \}.$$

For the meromorphic function λ = θ z ( -a 1 ) ... ( z -a k ) θ k ( z ) , a 1 + . . . + a k = 0 there is a unique operator L λ ( ) = v k ( n T ) k + . . . + v 0 ( n ) such that L λ ψ ( ) = λψ. Coefficients of L λ ( ) can be found from the last identity (see [39]). Operators L λ ( ) for different λ form a commutative ring of difference operators. This example can be generalized from the elliptic spectral curves to the principle polarized abelian spectral varieties. It allows to construct commuting difference operators in several discrete variables with matrix coefficients (see [39]).

At l > 1 common eigenfunctions cannot be found explicitly. This is the main difficulty for constructing higher rank operators and higher rank solutions of the 2DToda chain. Recall the needed results of [2]. One-point commuting operators of rank l have the form

$$L = \sum _ { i = - N r _ { - } } ^ { N r _ { + } } u _ { i } ( n ) T ^ { i }, \quad A = \sum _ { i = - M r _ { - } } ^ { M r _ { + } } v _ { i } ( n ) T ^ { i }, \\ + \, r \,. \, \text{ } \, \text{ } \, \text{ } \, \text{ } \, \text{ } \, \text{ } \, \text{ } \, \text{ } \, \text{ } \, \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } \text{$$

where l = r -+ r + , ( N,M ) = 1. Consider the space H ( z ) of solutions of the equation Ly = zy. We have dim H ( z ) = N r ( -+ r + ) . The operator A defines the linear operator A z ( ) on H ( z . ) Let us choose the basis ϕ i ( n ) in H ( z ), satisfying the normalization conditions ϕ i ( n ) = δ in , -Nr -≤ i, n < Nr . + The components of A z ( ) in the basis ϕ i ( n ) are polynomials in z . The characteristic polynomial of A z ( ) has the form det( w -A z ( )) = R w,z . l ( ) Polynomial R defines the spectral curve Γ, i.e.

$$L \psi = z \psi, \quad A \psi = w \psi, \quad R ( z, w ) = 0.$$

Common eigenfunctions of L and A form a vector bundle of rank l over the affine part of Γ. Let us choose the basis in the space of common eigenfunctions such that

$$\psi _ { n } ^ { i } ( P ) = \delta _ { i, n }, \quad - r _ { - } \leq i, n < r _ { + }, \quad P = ( z, w ) \in \Gamma.$$

Functions ψ i n ( P ) have the pole divisor γ = γ 1 + . . . + γ lg of degree lg . We have the following identities

$$\alpha _ { s } ^ { j } \text{Res} _ { \gamma _ { s } } \psi _ { n } ^ { i } ( P ) = \alpha _ { s } ^ { i } \text{Res} _ { \gamma _ { s } } \psi _ { n } ^ { j } ( P ).$$

The pair ( γ, α ) is called the Tyurin parameters , where α is the set of vectors

$$\alpha _ { 1 }, \dots, \alpha _ { l g }, \quad \alpha _ { s } = ( \alpha _ { s } ^ { - r _ { - } }, \dots, \alpha _ { s } ^ { r _ { + } - 1 } ).$$

The Tyurin parameters define a stable holomorphic vector bundle on Γ of degree lg with holomorphic sections ζ -r -, . . . , ζ r + -1 , where γ is the divisor of their linear dependence ∑ r + -1 j = -r -α ζ j s j ( γ s ) = 0 . Let Ψ( n, P ) be the Wronski matrix with the components Ψ ( ij n, P ) = ψ i n + j ( P , ) -r -≤ i, j < r + . Function detΨ( n, P ) is holomorphic in the neighbourhood of q = ∞ . The pole divisor of detΨ( n, P ) is γ , the zero divisor of detΨ( n, P ) is γ n ( ) = γ 1 ( n ) + · · · + γ lg ( n , ) herewith γ (0) = γ . Consider the matrix function χ n, P ( ) = Ψ( n +1 , P )Ψ -1 ( n, P ) ,

$$\text{uncon } \chi ( n, r ) = \Psi ( n + 1, r ) \Psi ( n, r ), \\ \chi ( n, P ) = \left ( \begin{array} { c c c c c } 0 & 1 & 0 & \dots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & \dots & 0 \\ \dots & \dots & \dots & \dots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \dots & 1 \\ \chi _ { - r _ { - } } ( n, P ) & \chi _ { - r _ { - } + 1 } ( n, P ) & \chi _ { - r _ { - } + 2 } ( n, P ) & \dots & \chi _ { r _ { + } - 1 } ( n, P ) \end{array} \right ). \\ \text{$\kappa }$$

In the neighbourhood of q we have χ i ( n, k ) = k -1 δ i, 0 -f i ( n, k ) , where k is a local parameter near q , f i ( n, k ) is an analytical function in the neighbourhood of q .

Theorem (I.M. Krichever, S.P. Novikov)

The matrix function χ n, P ( ) has simple poles in γ s ( n ) , and

$$\alpha _ { s } ^ { j } ( n ) \text{Res} _ { \gamma _ { s } ( n ) } \chi _ { i } ( n, P ) = \alpha _ { s } ^ { i } ( n ) \text{Res} _ { \gamma _ { s } ( n ) } \chi _ { j } ( n, P ).$$

Points γ s ( n +1) are zeros of det χ n, P ( )

$$\det \chi ( n, \gamma _ { s } ( n + 1 ) ) = 0.$$

Vectors α j ( n +1) = ( α -r -s ( n +1) , . . . , α r + -1 s ( n +1)) satisfy

$$\alpha _ { s } ( n + 1 ) \chi ( n, \gamma _ { s } ( n + 1 ) ) = 0.$$

Equations (16)-(18) define the discrete dynamics of the Tyurin parameters. In [2] solutions of (16)-(18) are found at g = 1 , l = 2. The corresponding operators in the simplest case have the form

$$L = L _ { 2 } ^ { 2 } - \wp ( \gamma _ { n } ) - \wp ( \gamma _ { n - 1 } ),$$

L 2 is the difference Schr¨dinger operator o L 2 = T + v n + c n T -1 with the coefficients

$$c _ { n } = \frac { 1 } { 4 } ( s _ { n - 1 } ^ { 2 } - 1 ) F ( \gamma _ { n }, \gamma _ { n - 1 } ) F ( \gamma _ { n - 2 }, \gamma _ { n - 1 } ), \quad v _ { n } = \frac { 1 } { 2 } ( s _ { n - 1 } F ( \gamma _ { n }, \gamma _ { n - 1 } ) - s _ { n } F ( \gamma _ { n - 1 }, \gamma _ { n } ) ),$$

where

$$F ( u, v ) = \zeta ( u + v ) - \zeta ( u - v ) - 2 \zeta ( v ).$$

Here, ℘ u , ζ ( ) ( u ) are the Weierstrass functions, s n , γ n are the functional parameters.

## 3 Proof of Theorems 1-4

Let Γ be the hyperelliptic spectral curve (1), L , L 4 4 g +2 are operators of the form (2) with the properties (3). Matrix χ n, P ( ) = Ψ( n +1 , P )Ψ -1 ( n, P ) has the form

$$\chi ( n, P ) = \left ( \begin{array} { c c } 0 & 1 \\ \chi _ { 1 } ( n, P ) & \chi _ { 2 } ( n, P ) \end{array} \right ).$$

The functions χ , χ 1 2 have the following expansions in the neighbourhood of q = ∞ :

$$\chi _ { 1 } ( n ) = b _ { 0 } ( n ) + b _ { 1 } ( n ) k + \dots, \quad \chi _ { 2 } ( n ) = 1 / k + e _ { 0 } ( n ) + e _ { 1 } ( n ) k + \dots, \quad ( 1 9 )$$

where k = 1 √ z .

## Lemma 1 The operator

$$L _ { 4 } = T ^ { 2 } + u _ { 1 } ( n ) T + u _ { 0 } ( n ) + u _ { - 1 } ( n ) T ^ { - 1 } + u _ { - 2 } ( n ) T ^ { - 2 }$$

has the coefficients:

$$u _ { 1 } ( n ) = - e _ { 0 } ( n ) - e _ { 0 } ( n + 1 ), \quad u _ { 0 } ( n ) = e _ { 0 } ^ { 2 } ( n ) + e _ { 1 } ( n ) - e _ { 1 } ( n + 1 ) - b _ { 0 } ( n ) - b _ { 0 } ( n + 1 ),$$

$$u _ { - 1 } ( n ) = b _ { 0 } ( n ) \left ( e _ { 0 } ( n ) + e _ { 0 } ( n - 1 ) - \frac { b _ { 1 } ( n - 1 ) } { b _ { 0 } ( n - 1 ) } \right ) - b _ { 1 } ( n ), \quad u _ { - 2 } ( n ) = b _ { 0 } ( n ) b _ { 0 } ( n - 1 ).$$

If b 1 ( n ) = 0 , e 0 ( n ) = 0 , then L 4 can be written in the form (6), where

$$V _ { n } = - b _ { 0 } ( n ), \quad W _ { n } = - e _ { 1 } ( n ) - e _ { 1 } ( n + 1 ).$$

Proof Using (4) let us express ψ n +2 ( P ) and ψ n -2 ( P ) via ψ n -1 ( P , ψ ) n ( P , χ ) 1 ( n, P ) , χ 2 ( n, P )

$$\psi _ { n + 2 } = \psi _ { n - 1 } \chi _ { 1 } ( n ) \chi _ { 2 } ( n + 1 ) + \psi _ { n } ( \chi _ { 1 } ( n + 1 ) + \chi _ { 2 } ( n ) \chi _ { 2 } ( n + 1 ) ), \quad \psi _ { n - 2 } = \frac { \psi _ { n } - \psi _ { n - 1 } \chi _ { 2 } ( n - 1 ) } { \chi _ { 1 } ( n - 1 ) },$$

and substitute it in L ψ 4 n = zψ n . We get P 1 ( n, P ) ψ n ( P ) + P 2 ( n, P ) ψ n -1 ( P ) = zψ n ( P , ) where

$$P _ { 1 } ( n ) = \chi _ { 1 } ( n + 1 ) + \chi _ { 2 } ( n + 1 ) \chi _ { 2 } ( n ) + u _ { 1 } ( n ) \chi _ { 2 } ( n ) + u _ { 0 } ( n ) + \frac { u _ { - 2 } ( n ) } { \chi _ { 1 } ( n - 1 ) },$$

$$P _ { 2 } ( n ) = \chi _ { 2 } ( n + 1 ) \chi _ { 1 } ( n ) + u _ { 1 } ( n ) \chi _ { 1 } ( n ) + u _ { - 1 } ( n ) - u _ { - 2 } ( n ) \frac { \chi _ { 2 } ( n - 1 ) } { \chi _ { 1 } ( n - 1 ) }.$$

Consequently we have

$$P _ { 1 } = z = \frac { 1 } { k ^ { 2 } }, \quad P _ { 2 } = 0.$$

From (19), (20) it follows that

$$P _ { 1 } - \frac { 1 } { k ^ { 2 } } = \frac { e _ { 0 } ( n ) + e _ { 0 } ( n + 1 ) + u _ { 1 } ( n ) } { k } + ( b _ { 0 } ( n + 1 ) + e _ { 0 } ( n ) e _ { 0 } ( n + 1 ) + e _ { 1 } ( n ) +$$

$$e _ { 1 } ( n + 1 ) + u _ { 0 } ( n ) + e _ { 0 } ( n ) u _ { 1 } ( n ) + \frac { u _ { - 2 } ( n ) } { b _ { 0 } ( n - 1 ) } \Big ) + O ( k ) = 0,$$

$$P _ { 2 } = \frac { b _ { 0 } ( n ) - \frac { u _ { - 2 } ( n ) } { b _ { 0 } ( n - 1 ) } } { k } + ( b _ { 1 } ( n ) + b _ { 0 } ( n ) e _ { 0 } ( n + 1 ) + b _ { 0 } ( n ) u _ { 1 } ( n ) + \\........................................................................................................................................................................................................$$

$$u _ { - 1 } ( n ) + \frac { b _ { 1 } ( n - 1$$

This yields the formulas for the coefficients of L . 4 By direct calculations one can check that if b 1 ( n ) = e 0 ( n ) = 0, then L 4 has the form (6). Lemma 1 is proved.

Thus if χ , χ 1 2 satisfy (5), then b 1 ( n ) = e 0 ( n ) = 0 , and hence L 4 has the form (6). Operators L 4 -z and L 4 g +2 -w have the common right divisor T -χ 2 ( n ) -χ 1 ( n T ) -1 , i.e.

$$L _ { 4 } - z = l _ { 1 } ( T - \chi _ { 2 }$$

where l 1 and l 2 are operators of orders 2 and 4 g . Let us assume that (5) holds. Then

$$( T + V _ { n } T ^ { - 1 } ) ^ { 2 } + W _$$

where χ 1 , χ 2 satisfy the equations

$$V _ { n - 1 } V _ { n } + \chi _ { 1 } ( n -$$

$$\begin{array} {$$

We have det χ n, P ( ) = -χ 1 ( n, P ) = detΨ( n + 1 , P )(detΨ( n, P )) -1 . The degree of the zero divisor γ n ( ) of detΨ( n, P ) is 2 g. Since χ 1 is invariant under the involution σ , the divisor γ n ( ) has the form

$$\gamma ( n ) = \gamma _ { 1 } ( n ) + \sigma \gamma _ { 1 } ( n ) + \dots + \gamma _ { g } ( n ) + \sigma \gamma _ { g } ( n ).$$

Let γ i ( n ) have the coordinates ( µ i ( n , w ) i ( n )) . We introduce the polynomial in z

$$Q _ { n } = ( z - \mu _ { 1 } ( n ) ) \dots ( z - \mu _ { g } ( n ) ).$$

From (17) we have χ 1 ( n, P ) = b 0 ( n ) Q n +1 Q n , where b 0 ( n ) is some function. In the neighbourhood of q we have

$$\chi _ { 1 } = b _ { 0 } ( n ) + b _ { 2 } ( n ) k ^ { 2 } + O ( k ^ { 4 } ).$$

By Lemma 1 V n = -b 0 ( n , ) so we get χ 1 ( n, P ) = -V n Q n +1 Q n .

Since the pole divisor of χ 2 ( n, P ) is γ n ( ) and in the neighborhood of q we have (19), then χ 2 ( n, P ) = w Q n .

If χ 1 ( n, P ) = -V n Q n +1 Q n and χ 2 ( n, P ) = w Q n , then (22) holds identically, and (21) is reduced to (8). Theorem 1 is proved.

To prove Theorems 2-4 it is sufficient to prove that for potentials V , W n n from Theorems 2-4 there are polynomials Q n ( z ) of degree g in z which satisfy (9) (and hence satisfy (8)).

## 3.1 Theorem 2

Let V n = r n 3 3 + r n 2 2 + r n 1 + r , W 0 n = g g ( +1) r n, 3 then (9) takes the form

Q n -1 ( n r 3 3 + n r 2 2 + nr 1 + r 0 )+ Q n ( z -2 n r 3 3 -n 2 (2 r 2 +3 r 3 ) -n (2 r 1 +2 r 2 +3 r 3 + ( g g +1) r 3 )

$$- \left ( 2 r _ { 0 } + r _ { 1 } + r _ { 2 } + r _ { 3 } \right ) \right ) - Q _ { n + 2 } \left ( z - 2 n ^ { 3 } r _ { 3 } - n ^ { 2 } ( 2 r _ { 2 } + 9 r _ { 3 } ) - \\ \wedge$$

n

(2

r

1

+6

r

2

+15

r

3

+ (1 +

g

g r

)

3

)

-

(2

r

0

+3

r

1

+5

r

2

+9

r

3

+ (

g g

+1)

r

3

))

-

$$Q _ { n + 3 } \left ( n ^ { 3 } r _ { 3 } + n ^ { 2 } ( r _ { 2 } + 6 r _ { 3 } ) + n ( r _ { 1 } + 4 r _ { 2 } + 1 2 r _ { 3 } ) + r _ { 0 } + 2 r _ { 1 } + 4 r _ { 2 } + 8 r _ { 3 } \right ) & = 0. \quad ( 2 3 ) \\ \text{Let us take the following ansatz for } Q _ { n } ( z )$$

Let us take the following ansatz for Q n ( z )

$$Q _ { n } = \delta _ { g } n ^ { g } + \dots + \delta _ { 1 } n + \delta _ { 0 }, \quad \delta _ { i } = \delta _ { i } ( z ),$$

then (23) can be rewritten in the form

$$\beta _ { g + 3 } ( z ) n ^ { g + 3 } + \beta _ { g + 2 } ( z ) n ^ { g + 2 } + \dots + \beta _ { 0 } ( z ) = 0$$

for some β s ( z ). Potentials V , W n n have the following remarkable properties: it turns out that

$$\beta _ { g } = \beta _ { g + 1 } = \beta _ { g + 2 } = \beta _ { g + 3 } = 0$$

automatically (this can be checked by direct calculations). From (23) we find β s

$$\beta _ { s } & = r _ { 3 } ( 2 s + 1 ) ( g ( g + 1 ) - s ( s + 1 ) ) \delta _ { s } + \sum _ { m = 1 } ^ { g } \left ( ( - 1 ) ^ { m } \left ( C _ { s + m } ^ { m } r _ { 0 } - C _ { s + m } ^ { m + 1 } r _ { 1 } \, + \\ _ { \dots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots \cdots }.$$

$$\overline { m = 1 } \quad \begin{array} { c } \\ C ^ { m + 2 } _ { s + m } r _ { 2 } - C ^ { m + 3 } _ { s + m } r _ { 3 } \right ) + 2 ^ { m } \left ( C ^ { m } _ { s + m } ( 2 r _ { 0 } + 3 r _ { 1 } + 5 r _ { 2 } + 9 r _ { 3 } + g ( g + 1 ) r _ { 3 } - z ) + \\ 2 C ^ { m + 1 } _ { s + m } ( 2 r _ { 1 } + 6 r _ { 2 } + 1 5 r _ { 3 } + g ( g + 1 ) r _ { 3 } ) + 4 C ^ { m + 2 } _ { s + m } ( 2 r _ { 2 } + 9 r _ { 3 } ) + 1 6 C ^ { m + 3 } _ { s + m } r _ { 3 } \right ) - \\ 3 ^ { m } \left ( C ^ { m } _ { s + m } ( r _ { 0 } + 2 r _ { 1 } + 4 r _ { 2 } + 8 r _ { 3 } ) + 3 C ^ { m + 1 } _ { s + m } ( r _ { 1 } + 4 r _ { 2 } + 1 2 r _ { 3 } ) + \\ 3 ^ { m } \left ( C ^ { m } _ { s + m } ( r _ { 0 } + 2 r _ { 1 } + 4 r _ { 2 } + 8 r _ { 3 } ) + 3 C ^ { m + 1 } _ { s + m } ( r _ { 1 } + 4 r _ { 2 } + 1 2 r _ { 3 } ) + \\ 9 C ^ { m + 2 } _ { s + m } ( r _ { 2 } + 6 r _ { 3 } ) + 2 7 C ^ { m + 3 } _ { s + m } r _ { 3 } \right ) \right ) \delta _ { s + m }, \\ \text{where } 0 \leq s < g - 1, \text{ } C ^ { k } _ { m } = \frac { m! } { k! ( m - k )! } \text{ at } m \geq k, C ^ { k } _ { m } = 0 \text{ at } m < k, \delta _ { g } \text{ is a constant and} \\ \delta _ { s } = 0, \text{ if } s > g. \text{ From } \beta _ { s } = 0 \text{ we express } \delta _ { s } \text{ via } \delta _ { s + 1 }, \dots, \delta _ { g }. \text{ In particular}, \end{array}$$

where 0 ≤ s < g -1 , C k m = m ! k !( m k -)! at m ≥ k, C k m = 0 at m < k, δ g is a constant and δ s = 0 , if s > g. From β s = 0 we express δ s via δ s +1 , . . . , δ g . In particular,

$$\delta _ { g - 1 } = \frac { \delta _ { g } ( 2 g ^ { 2 } r _ { 2 } + g ( g + 1 ) r _ { 3 } + 2 z ) } { 2 ( 2 g - 1 ) r _ { 3 } }.$$

For a suitable δ g we have Q n = z g + α g -1 ( n z ) g -1 + . . . + α 0 ( n . ) So we proved that there exists Q n satisfying (9). Theorem 2 is proved.

In [5] it was proved that

$$\mathcal { L } _ { 4 } ^ { \ddagger } = ( \partial _ { x } ^ { 2 } + r _ { 3 } x ^ { 3 } + r _ { 2 } x ^ { 2 } + r _ { 1 } x + r _ { 0 } ) ^ { 2 } + g ( g + 1 ) r _ { 3 } x$$

commutes with a differential operator L /sharp 4 g +2 of order 4 g + 2. The operator L /sharp 4 is a discrete analogue of L /sharp 4 . At g = 1 the operators L /sharp 4 , L /sharp 6 were found by Dixmier [10]. The operators L /sharp 4 , L /sharp 4 g +2 define a commutative subalgebra in the first Weyl algebra.

Let us consider the algebra W generated by two elements p and q with the relation [ p, q ] = p. Since [ T, n ] = T , the algebra is isomorphic to the algebra of difference operators with polynomial coefficients. The algebra W has the following automorphisms

$$H \, \colon W \to W, \quad H ( p ) = p, \quad H ( q ) = q + G ( p ),$$

where G is an arbitrary polynomial. Operators L /sharp 4 , L /sharp 4 g +2 define the commutative subalgebra in W . Consequently, if we replace n → n + G T ( ) in L /sharp 4 , L /sharp 4 g +2 , then we obtain the new commuting difference operators with polynomial coefficients.

## 3.2 Theorem 3

Let V n = r a 1 n + r 0 , W n = ( a 2 g +1 -a g +1 -a g +1) r a 1 n -g , then (9) takes the form

$$Q _ { n + 2 } \left ( 2 r _ { 0 } + a ^ { n + 1 - g } r _ { 1 } + a ^ { n + g + 2 } r _ { 1 } - z \right ) - Q _ { n + 3 } \left ( r _ { 0 } + a ^ { n + 2 } r _ { 1 } \right ) = 0.$$

Let Q n = B a g gn + B g -1 a ( g -1) n + . . . + B a 1 n + B , B 0 i = B z . i ( ) We introduce the notation y = a n , then Q n = B y g g + · · · + B 0 , and (25) takes the form

$$Q _ { n - 1 } \left ( r _ { 0 } + a ^ { n } r _ { 1 } \right ) + Q _ { n } \left ( z - 2 r _ { 0 } - a ^ { n - g } r _ { 1 } - a ^ { n + g + 1 } r _ { 1 } \right ) + \\ Q _ { n + 2 } \left ( 2 r _ { 0 } + a ^ { n + 1 - g } r _ { 1 } + a ^ { n + g + 2 } r _ { 1 } - z \right ) - Q _ { n + 3 } \left ( r _ { 0 } + a ^ { n + 2 } r _ { 1 } \right ) = 0. \\ \varepsilon = B _ { g } a _ { \begin{smallmatrix} g ^ { n } \\ \varepsilon \end{smallmatrix} } ^ { g n } + B _ { g - 1 } a _ { \begin{smallmatrix} a ^ { ( g - 1 ) n } + \dots + B _ { 1 } a ^ { n } + B _ { 0 }, B _ { i } = B _ { i } ( z ). \text{ We introduce the nc} \end{smallmatrix} }$$

$$\sum _ { s = 0 } ^ { g } B _ { s } ( a ^ { - g - s } ( a ^ { g } - a ^ { s } ) ( a ^ { g + s + 1 } - 1 ) ( a ^ { 2 s + 1 } - 1 ) r _ { 1 } y ^ { s + 1 } - a ^ { - s } ( a ^ { 2 s } - 1 ) ( ( a ^ { s } - 1 ) ^ { 2 } r _ { 0 } + a ^ { s } z ) y ^ { s } ) =$$

$$\sum _ { s = 1 } ^ { g } y ^ { s } ( B _ { s } a ^ { - s } ( 1 - a ^ { 2 s } ) ( ( a ^ { s } - 1 ) ^ { 2 } r _ { 0 } + a ^ { s } z ) + B _ { s - 1 } a ^ { 1 - g - s } ( a ^ { g } - a ^ { s - 1 } ) ( a ^ { g + s } - 1 ) ( a ^ { 2 s - 1 } - 1 ) r _ { 1 } ) = 0. \\ \dots \dots$$

Hence we obtain

$$B _ { s - 1 } = B _ { s } \frac { a ^ { - s } ( a ^ { 2 s } - 1 ) ( ( a ^ { s } - 1 ) ^ { 2 } r _ { 0 } + a ^ { s } z ) } { a ^ { 1 - g - s } ( a ^ { g } - a ^ { s - 1 } ) ( a ^ { g + s } - 1 ) ( a ^ { 2 s - 1 } - 1 ) r _ { 1 } }, \quad s = 1, \dots, g.$$

Thus we found the polynomial Q , n satisfying (9). Theorem 3 is proved.

The operator L /check 4 is a discrete analogue of

$$\mathcal { L } _ { 4 } ^ { \vee } = ( \partial _ { x } ^ { 2 } + r _ { 1 } a ^ { x } + r _ { 0 } ) ^ { 2 } + g ( g + 1 ) r _ { 1 } a ^ { x }$$

from [26], which commutes with a differential operator of order 4 g +2.

## 3.3 Theorem 4

Let V n = r 1 cos( n ) + r , 0 W n = -4 r 1 sin( g 2 ) sin( g +1 2 ) cos( n + 1 2 ) . Equation (9) takes the form

$$& Q _ { n - 1 } \left ( r _ { 0 } + r _ { 1 } \cos ( n ) \right ) + Q _ { n } \left ( z - 2 r _ { 0 } - 2 r _ { 1 } \cos ( g + \frac { 1 } { 2 } ) \cos ( n + \frac { 1 } { 2 } ) \right ) - \\ Q _ { n + 2 } \left ( z - 2 r _ { 0 } - 2 r _ { 1 } \cos ( g + \frac { 1 } { 2 } ) \cos ( n + \frac { 3 } { 2 } ) \right ) - Q _ { n + 3 } \left ( r _ { 0 } + r _ { 1 } \cos ( n + 2 ) \right ) = 0. \\ & \text{Let us take the following ansatz}$$

Let us take the following ansatz

$$Q _ { n } = A _ { g } \cos ( g n ) + A _ { g - 1 } \cos ( ( g - 1 ) n ) + \dots + A _ { 1 } \cos ( n ) + A _ { 0 }, \quad A _ { i } = A _ { i } ( z ).$$

We substitute Q n in (26) and after some simplifications we obtain

$$A _ { 0 } = A _ { 1 } \frac { ( z - 2 r _ { 0 } + 2 r _ { 0 } \cos ( 1 ) ) \sin ( 1 ) } { 2 r _ { 1 } ( \cos ( g + \frac { 1 } { 2 } ) - \cos ( \frac { 1 } { 2 } ) ) \sin ( \frac { 1 } { 2 } ) },$$

$$A _ { s - 1 } = \frac { A _ { s } ( z - 2 r _ { 0 } + 2 r _ { 0 } \cos ( s ) ) \sin ( s ) + A _ { s + 1 } r _ { 1 } ( \cos ( s - \frac { 3 } { 2 } ) - \cos ( g + \frac { 1 } { 2 } ) ) \sin ( s - \frac { 3 } { 2 } ) } { r _ { 1 } ( \cos ( g + \frac { 1 } { 2 } ) - \cos ( s - \frac { 1 } { 2 } ) ) \sin ( s - \frac { 1 } { 2 } ) },$$

where 2 ≤ s ≤ g , A g +1 = 0, A g is a suitable constant. We found Q n satisfying (9). Theorem 4 is proved.

The operator L /natural 4 is a discrete analogue of

$$\mathcal { L } _ { 4 } ^ { \natural } = ( \partial _ { x } ^ { 2 } + r _ { 1 } \cos ( x ) + r _ { 0 } ) ^ { 2 } + g ( g + 1 ) r _ { 1 } \cos ( x )$$

from [29], which commutes with a differential operator of order 4 g +2. Let us consider several examples.

Example 1 We introduce the notation f ( n ) = r n 3 3 + r n 2 2 + r n 1 + r 0 . The operator

$$L _ { 4 } ^ { \mathfrak { z } } = ( T + f ( n ) T ^ { - 1 } ) ^ { 2 } + 2 r _ { 3 } n$$

commutes with

$$L _ { 6 } ^ { t } & = T ^ { 3 } + 3 ( f ( n ) + f ^ { \prime } ( n ) + f ^ { \prime \prime } ( n ) + 4 r _ { 3 } ) T + 3 ( f ( n ) + 3 r _ { 3 } n + r _ { 2 } ) T ^ { - 1 } + \\ & ( f ( n - 2 ) f ^ { \prime } ( n ) + 2 f ^ { \prime \prime } ( n ) - 8 r _ { 3 } ) ( f ( n ) - f ^ { \prime } ( n ) + 3 r _ { 3 } n - r _ { 3 } + r _ { 2 } ) f ( n ) T ^ { - 3 }.$$

The spectral curve is

$$w ^ { 2 } = z ^ { 3 } + ( 2 r _ { 2 } + 3 r _ { 3 } ) z ^ { 2 } + ( r _ { 1 } r _ { 3 } + ( r _ { 2 } + r _ { 3 } ) ( r _ { 2 } + 3 r _ { 3 } ) ) z + r _ { 3 } ( ( r _ { 2 } + r _ { 3 } ) ( r _ { 1 } + r _ { 2 } + r _ { 3 } ) - r _ { 0 } r _ { 3 } ).$$

Example 2 The operator

$$L _ { 4 } ^ { \breve { \cdot } } = ( T + ( r _ { 1 } a ^ { n } + r _ { 0 } ) T ^ { - 1 } ) ^ { 2 } + r _ { 1 } ( a ^ { 3 } - a ^ { 2 } - a + 1 ) a ^ { n - 1 }$$

commutes with

$$L _ { 6 } ^ { \cdot } = T ^ { 3 } + \left ( r _ { 0 } ( a + 1 + a ^ { - 1 } ) + r _ { 1 } a ^ { n - 1 } ( a ^ { 4 } + a ^ { 2 } + 1 ) \right ) T + ( a + 1 + a ^ { - 1 } ) ( r _ { 1 } a ^ { n } + r _ { 0 } ) \times \\ ( r _ { 1 } a ^ { n + 1 } - r _ { 1 } a ^ { n } + r _ { 1 } a ^ { n - 1 } + r _ { 0 } ) T ^ { - 1 } + ( r _ { 1 } a ^ { n } + r _ { 0 } ) ( r _ { 1 } a ^ { n - 1 } + r _ { 0 } ) ( r _ { 1 } a ^ { n - 2 } + r _ { 0 } ) T ^ { - 3 }. \\ \text{The spectral curve is $w^{2}=z^{3}+\frac{2r_{0}(a-1)^{2}} a z^{2}+\frac{r_{0}(a-1)^{4}} a z.$$

The spectral curve is a a

## Example 3 The operator

$$L _ { 4 } ^ { \natural } & = ( T + ( r _ { 1 } \cos ( n ) + r _ { 0 } ) T ^ { - 1 } ) ^ { 2 } - 4 r _ { 1 } \sin ( \frac { 1 } { 2 } ) \sin ( 1 ) \cos ( n + \frac { 1 } { 2 } ) \\ \dots$$

commutes with

$$L _ { 6 } ^ { \natural } = T ^ { 3 } + ( 2 \cos ( 1 ) + 1 ) ( r _ { 1 } ( 2 \cos ( 1 ) - 1 ) \cos ( n + 1 ) + r _ { 0 } ) \, T +$$

$$( 2 \cos ( 1 ) + 1 ) ( r _ { 1 } \cos ( n ) + r _ { 0 } ) ( r _ { 1 } ( 2 \cos ( 1 ) - 1 ) \cos ( n ) + r _ { 0 } ) T ^ { - 1 } +$$

$$( r _ { 1 } \cos ( n - 1 ) + r _ { 0 } ) ( r _ { 1 } \cos ( n - 2 ) + r _ { 0 } ) ( r _ { 1 } \cos ( n ) + r _ { 0 } ) T ^ { - 3 }.$$

The spectral curve is w 2 = z 3 -8 r 0 sin 2 ( 1 2 ) z 2 -8( r 2 1 (cos(1) + 1) -2 r 2 0 ) sin 4 ( 1 2 ) z.

Remark We see that the pairs of commuting operators L , L 4 4 g +2 and L 4 , L 4 g +2 have similar properties, and there are similar examples of such operators. It would be interesting to explain this duality. So far, our attempts to do so by some discretization were not successful.

Acknowledgements The authors are supported by a Grant of the Russian Federation for the State Support of Researches (Agreement No 14.B25.31.0029).

## Appendix

Consider the differential-difference system (13), (14).

Theorem 5 Let us assume that the potentials V n ( ) t , W t n ( ) of L 4 = ( T + V n ( ) t T -1 ) 2 + W t n ( ) satisfy (13), (14). We additionally assume that [ L , L 4 4 g +2 ] = 0 for some difference operator L 4 g +2 . Then Q n ( ) t associated with L 4 satisfies the evolution equation

$$\dot { Q } _ { n } = V _ { n } ( Q _ { n + 1 } - Q _ { n - 1 } ).$$

Equation (27) defines the symmetry of (8). At g = 1 functions V n ( ) t , W t n ( ) can be expressed via γ n ( ) using (9). t In this case the system (13), (14) and the equation (27) are reduced to one equation

$$\dot { \gamma } _ { n } = \frac { F _ { 1 } ( \gamma _ { n } ) ( \gamma _ { n - 1 } - \gamma _ { n + 1 } ) } { ( \gamma _ { n - 1 } - \gamma _ { n } ) ( \gamma _ { n } - \gamma _ { n + 1 } ) }.$$

This equation is a discrete analogue of the Krichever-Novikov equation, which appeared in the theory of rank two solutions of KP [1]. Equations similar to (13), (14) and (28) were considered in [40], [41].

Proof Using ( ∂ t -V n -1 ( ) t V n ( ) t T -2 ) ψ n = 0 , and (4) let us express ˙ ψ n -1 , ˙ ψ , ψ n ˙ n +1 , ψ n -2 , ψ n -3 in terms of ψ n -1 , ψ n , χ 1 ( n , χ ) 2 ( n )

$$\psi _ { n - 3 } \, \min \, \vee \, \psi _ { n - 1 }, \, \psi _ { n }, \, \lambda _ { 1 } \nwarrow, \, \lambda _ { 2 } \nwarrow \, \\ \dot { \psi } _ { n - 1 } = V _ { n - 2 } V _ { n - 1 } \psi _ { n - 3 }, \quad \dot { \psi } _ { n } = V _ { n - 1 } V _ { n } \psi _ { n - 2 }, \quad \dot { \psi } _ { n + 1 } = V _ { n } V _ { n + 1 } \psi _ { n - 1 }, \\ \psi _ { n - 2 } = \frac { \psi _ { n } - \psi _ { n - 1 } \chi _ { 2 } ( n - 1 ) } { \chi _ { 1 } ( n - 1 ) }, \\ \psi _ { n - 3 } = \frac { \psi _ { n - 1 } ( \chi _ { 1 } ( n - 1 ) + \chi _ { 2 } ( n - 2 ) \chi _ { 1 } ( n - 1 ) ) - \psi _ { n } \chi _ { 2 } ( n - 2 ) } { \chi _ { 1 } ( n - 2 ) \chi _ { 1 } ( n - 1 ) }. \\ \text{From } ( 4 ) \, \text{it follows that}$$

$$\dots$$

From (4) it follows that

$$\dot { \psi } _ { n + 1 } - \chi _ { 1 } ( n ) \dot { \psi } _ { n - 1 } - \dot { \chi } _ { 1 } ( n ) \psi _ { n - 1 } - \chi _ { 2 } ( n ) \dot { \psi } _ { n } - \dot { \chi } _ { 2 } ( n ) \psi _ { n } = \mathcal { A } _ { n } \psi _ { n } + \mathcal { B } _ { n } \psi _ { n - 1 } = 0,$$

where

$$\mathcal { A } _ { n } = V _ { n - 2 } V _ { n - 1 } \chi _ { 1 } ( n ) \chi _ { 2 } ( n - 2 ) - \chi _ { 1 } ( n - 2 ) ( V _ { n - 1 } V _ { n } \chi _ { 2 } ( n ) + \chi _ { 1 } ( n - 1 ) \dot { \chi } _ { 2 } ( n ) ),$$

$$\mathcal { B } _ { n } = V _ { n - 2 } V _ { n - 1 } \chi _ { 1 } ( n ) \left ( \chi _ { 1 } ( n - 1 ) + \chi _ { 2 } ( n - 2 ) \chi _ { 2 } ( n - 1 ) \right ) +$$

+ V χ n 1 ( n -2) ( V n +1 χ 1 ( n -1) + V n -1 χ 2 ( n -1) χ 2 ( n )) -χ 1 ( n -2) χ 1 ( n -1) ˙ χ 1 ( n . )

Consequently, we have A n = B n = 0. For χ 1 = -V n ( ) t Q n +1 ( ) t Q n ( ) t , χ 2 = w Q n ( ) t it follows from (8) and from A n = B n = 0 that Q n ( ) satisfies (27). t Theorem 5 is proved.

## References

- [1] I.M. Krichever, S.P. Novikov, Holomorphic bundles over algebraic curves and nonlinear equations , Russian Math. Surveys, 35 :6 (1980), 53-79.

- [2] I.M. Krichever, S.P. Novikov, Two-dimensional Toda lattice, commuting difference operators, and holomorphic bundles , Russian Math. Surveys, 58 :3 (2003), 473-510.

- [3] I.M. Krichever, Integration of nonlinear equations by the methods of algebraic geometry , Functional Anal. Appl., 11 :1 (1977), 12-26.

- [4] I.M. Krichever, Commutative rings of ordinary linear differential operators , Functional Anal. Appl., 12 :3 (1978), 175-185.

- [5] A.E. Mironov, Self-adjoint commuting differential operators , Inventiones Math. 197 :2 (2014), 417-431.

- [6] A.E. Mironov, Commuting higher rank ordinary differential operators , Proceedings of the 6th European Congress of Math., (2013), 459-473.

- [7] G. Wallenberg, ¨ ber die Vertauschbarkeit homogener linearer Differenzenausdr¨cke U u , Arch. Math. Phys. bd., 15 (1909), 151-157.

- [8] J.L. Burchnall, I.W. Chaundy, Commutative ordinary differential operators , Proc. Lond. Math. Soc. Ser., 21 :2 (1923), 420-440.

- [9] I.M. Krichever, Algebraic curves and non-linear difference equations , Russian Math. Surveys, 33 :4 (1978), 255-256.

- [10] J. Dixmier, Sur les alg`bres de Weyl e , Bull. Soc. Math. France, 96 (1968), 209-242.

- [11] V.G. Drinfel'd, Commutative subrings of certain noncommutative rings , Functional Anal. Appl., 11 :1 (1977), 9-12.

- [12] S.P. Novikov, Commuting operators of rank l > 1 with periodic coefficients , (Russian) Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR, 263 :6 (1982), 1311-1314.

- [13] F.Kh. Baichorova, Z.S. Elkanova, Commuting differential operators of order 4 and 6 , Ufa Math. J. 5 :3 (2013), 11-19.

- [14] P. Dehornoy, Op´ erateurs diff´rentiels et courbes elliptiques e , Compositio Math., 43 :1 (1981), 71-99.

- [15] P.G. Grinevich, Rational solutions for the equation of commutation of differential operators , Functional Anal. Appl., 16 :1 (1982), 15-19.

- [16] P.G. Grinevich, S.P. Novikov, Spectral theory of commuting operators of rank two with periodic coefficients , Functional Anal. Appl., 16 :1 (1982), 19-20.

| [17] | F. Grunbaum, Commuting pairs of linear ordinary differential operators of orders four and six , Phys. D, 31 :3 (1988), 424-433. |

|--------|-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|

| [18] | G. Latham, Rank 2 commuting ordinary differential operators and Darboux conju- gates of KdV , Appl. Math. Lett., 8 :6 (1995), 73-78. |

| [19] | G. Latham, E. Previato, Darboux transformations for higher-rank Kadomtsev- Petviashvili and Krichever-Novikov equations , Acta Appl. Math., 39 (1995), 405- 433. |

| [20] | E. Previato, G. Wilson, Differential operators and rank 2 bundles over elliptic curves , Compositio Math., 81 :1 (1992), 107-119. |

| [21] | A.E. Mironov, A ring of commuting differential operators of rank 2 corresponding to a curve of genus 2 , Sbornik: Math., 195 :5 (2004), 711-722. |

| [22] | A.E. Mironov, Commuting rank 2 differential operators corresponding to a curve of genus 2 , Functional Anal. Appl., 39 :3 (2005), 240-243. |

| [23] | A.E. Mironov, On commuting differential operators of rank 2 , Siberian Electronic Math. Reports., 6 (2009), 533-536. |

| [24] | D. Zuo, Commuting differential operators of rank 3 associated to a curve of genus 2 , SIGMA, 8 (2012), 044. |

| [25] | O.I. Mokhov, Commuting differential operators of rank 3 and nonlinear differential equations , Mathematics of the USSR-Izvestiya, 35 :3 (1990), 629-655. |

| [26] | V.N. Davletshina, On self-adjoint commuting differential operators of rank two , Siberian Electronic Math. Reports, 10 (2013), 109-112. |

| [27] | V.N. Davletshina, Self-adjoint commuting differential operators of rank 2 and their deformations given by the soliton equations , Math. Notes (to appear). |

| [28] | V.N. Davletshina, E.I. Shamaev, On commuting differential opetators of rank two , Siberian Math. J. 55 :4 (2014). |

| [29] | A.E. Mironov, Periodic and rapid decay rank two self-adjoint commuting differential operators , American Math. Soc. Translations: Ser. 2 (to appear). |

| [30] | O.I. Mokhov, On commutative subalgebras of the Weyl algebra related to commuting operators of arbitrary rank and genus , Math. Notes, 94 :2 (2013), 298-300. |

| [31] | O.I. Mokhov, Commuting ordinary differential operators of arbitrary genus and arbitrary rank with polynomial coefficients , American Math. Soc. Translations: Ser. 2 (to appear). |

- [32] D. Mumford, An algebro-geometric construction of commuting operators and of solutions to the Toda lattice equation, Korteweg-de Vries equation and related nonlinear equations , Proceedings of the International Symposium on Algebraic Geometry (Kyoto Univ., Kyoto, 1977), Kinokuniya, Tokyo, 1978, 115-153.

- [33] A.E. Mironov, Discrete analogues of Dixmier operators , Sbornik: Math., 198 :10 (2007), 1433-1442.

- [34] S.P. Novikov, The periodic problem for the Korteweg-de Vries equation , Functional Anal. Appl., 8 (1974), 236-246.

- [35] B.A. Dubrovin, Periodic problems for the Korteweg-de Vries equation in the class of finite-gap potentials , Functional Anal. Appl., 9 :3 (1975), 215-223.

- [36] A.R. Its, V.B. Matveev, Schr¨dinger operators o with finite-gap spectrum and Nsoliton solutions of the Korteweg-de Vries equation , Theoretical and Math. Phys., 23 :1 (1975), 343-355.

- [37] B.A. Dubrovin, V.B. Matveev, S.P. Novikov, Non-linear equations of Kortewegde Vries type, finite-zone linear operators, and Abelian varieties , Russian Math. Surveys, 31 :1 (1976), 59-146.

- [38] I.M. Gel'fand, L.A. Dikii, Asimptotic behaviour of the resolvent of Sturm-Liouville equations and of the Korteweg-de Vries equations , Russian Math. Surveys, 30 :5 (1975), 77-113.

- [39] A.E. Mironov, A. Nakayashiki, Discretization of Baker-Akhiezer Modulas and Commuting Difference Operators in Several Discrete Variables , Trans. Moscow Math. Soc., 74 :2 (2013), 261-279.

- [40] V.E. Adler, A.B. Shabat, First integrals of generalized Toda chains , Theoretical and Math. Phys., 115 :3 (1998), 339-346.

- [41] D. Levi, P. Winternitz, R. Yamilov, Symmetries of the Continuous and Discrete Krichever-Novikov Equation , SIGMA, 7 (2011), 097.

- G.S. Mauleshova , Novosibirsk State University, Russia e-mail: guna [email protected]

- A.E. Mironov , Sobolev Institute of Mathematics, Novosibirsk, Russia and Laboratory of Geometric Methods in Mathematical Physics, Moscow State University e-mail: [email protected] | null | [

"Gulnara S. Mauleshova",

"Andrey E. Mironov"

] | 2014-08-01T09:42:22+00:00 | 2014-08-01T09:42:22+00:00 | [

"nlin.SI"

] | Difference Krichever-Novikov operators | In this paper we study commuting difference operators of rank two. We

introduce an equation on potentials $V(n),W(n)$ of the difference operator

$L_4=(T+V(n)T^{-1})^2+W(n)$ and some additional data. With the help of this

equation we find the first examples of commuting difference operators of rank

two corresponding to spectral curves of higher genus. |

1408.0114v1 | ## A Real-Time Spatial Index for In-Vehicle Units

Magnus Lie Hetland 1 and Ola Martin Lykkja 2

1 Norwegian University of Science and Technology, [email protected] 2 Q-Free ASA, Trondheim, Norway, [email protected]

## Abstract

We construct a spatial indexing solution for the highly constrained environment of an in-vehicle unit in a distributed vehicle tolling scheme based on satellite navigation ( gnss ). We show that a purely functional implementation of a high-fanout quadtree is a simple, practical solution that satisfies all the requirements of such a system.

## 1 Introduction

Open road tolling is an increasingly common phenomenon, with transponder-based tolling proposed as early as in 1959 [1], and a wide variety of more complex technologies emerging over the recent decades [2]. One of the more recent developments is the use of satellite navigation ( gnss ), with geographical points and zones determining the pricing [see, e.g., 3]. In this paper, we examine the feasibility of maintaining a geographical database in an in-vehicle unit, which can perform many of the tasks of such a location-based system independently.

This is a proof-of-concept application paper. Our main contributions can be summed up as follows: ( i ) We specify a set of requirements for a spatial database to be used in the highly constrained environment of a real-time, low-cost in-vehicle unit in Section 2; ( ii ) we construct a simple data structure that satisfies these requirements in Section 3; and ( iii ) we tentatively establish the feasibility of the solution through an experimental evaluation in Section 4. In the interest of brevity, some technical details have been omitted. See the report by Lykkja [4] for more information.

## 2 The Problem: Highly Constrained Spatial Indexing

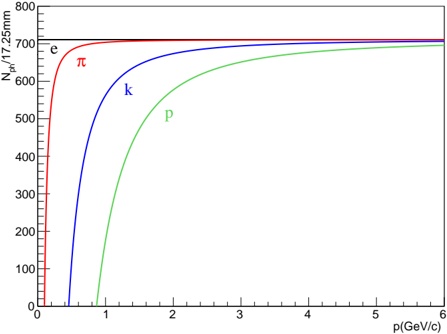

The basic functionality of our system is to retrieve relevant geographic (i.e., geometric) objects, that is, the tolling zones and virtual toll gantries that are within a certain distance of the vehicle. Given the real-time requirements and the limited speed of the available hardware, a plain linear scan of the data would be infeasible even with about 50 objects. A real map of zones and gantries would hold orders of magnitude more objects than that (c.f., Table 3). This calls for some kind of geometric or spatial indexing [5], although the context places some heavy constraints

This paper was presented at the NIK-2014 conference; see http://www.nik.no/ .

on the data structure used. One fundamental consideration is the complexity of the solution. In order to reduce the probability of errors, a simple data structure would be preferable. Beyond simplicity, and the need for high responsiveness, we have a rather non-standard hardware architecture to contend with.

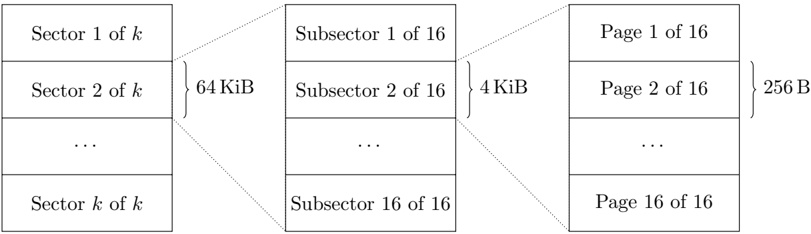

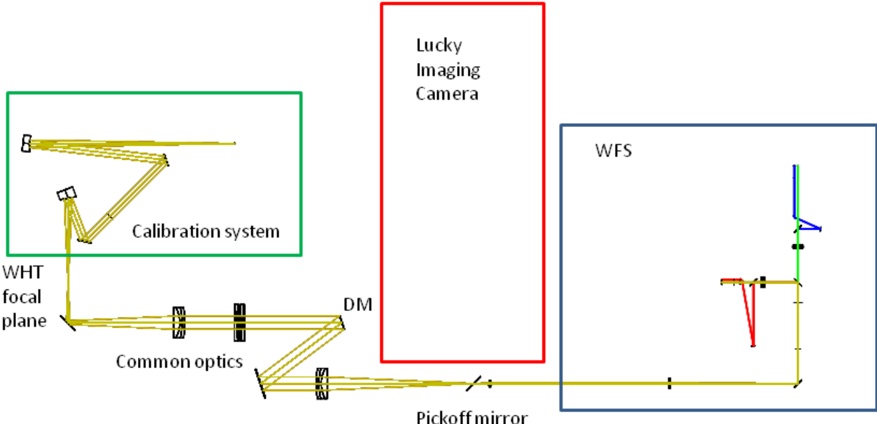

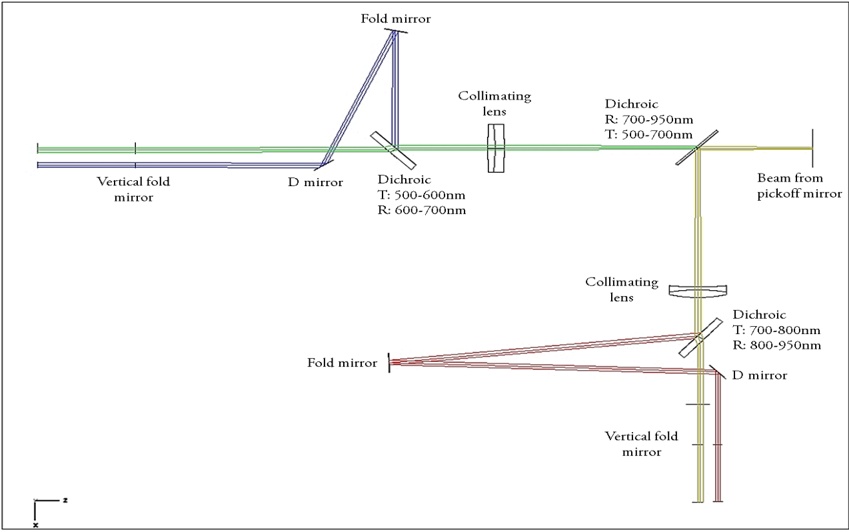

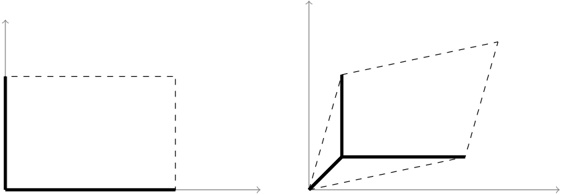

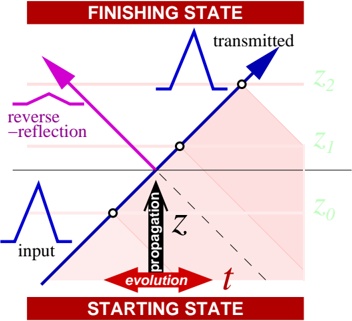

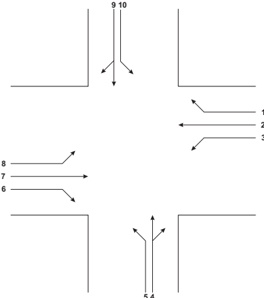

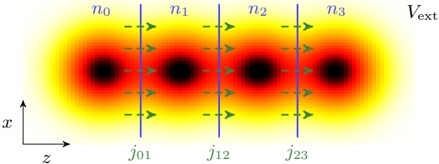

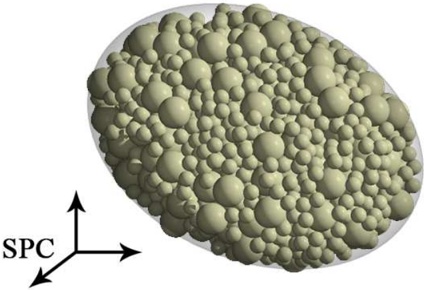

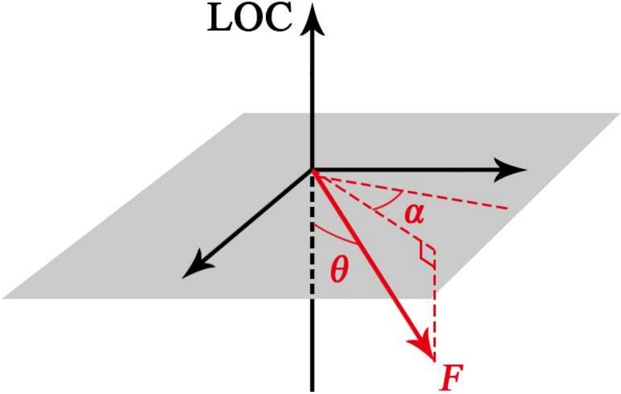

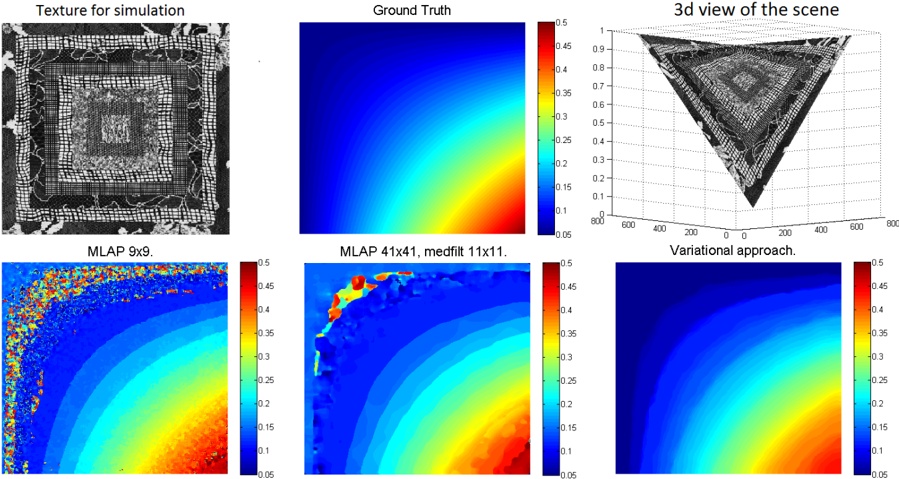

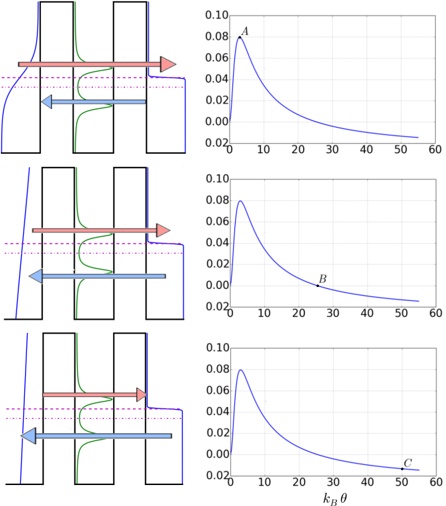

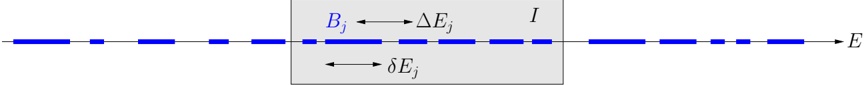

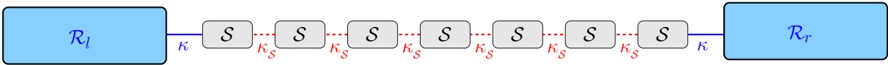

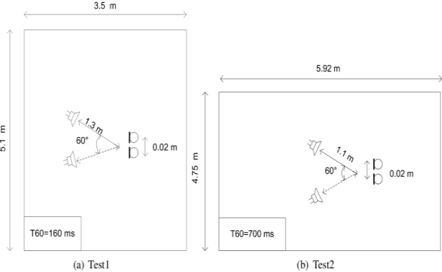

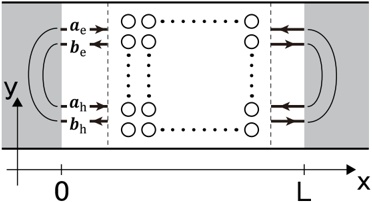

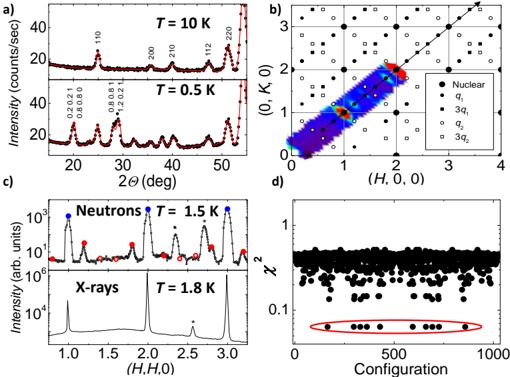

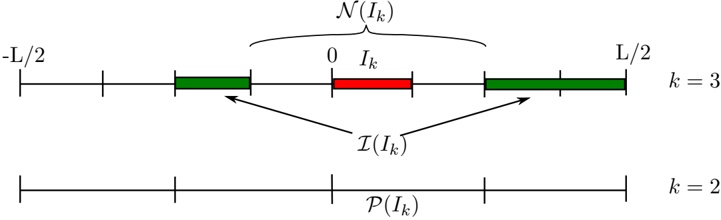

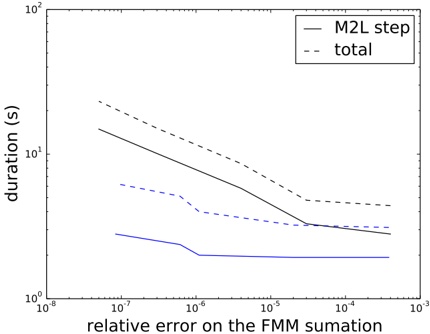

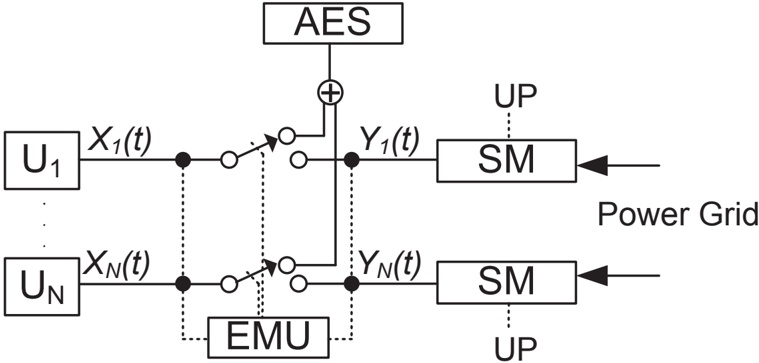

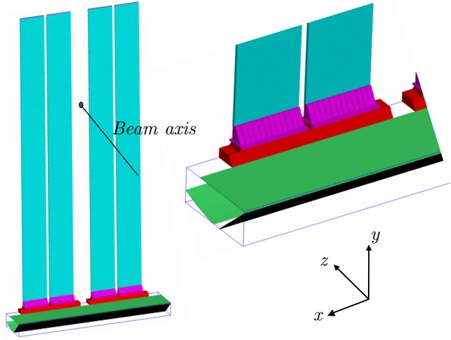

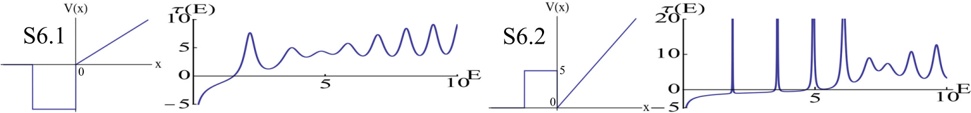

The memory of the on-board unit is assumed to be primarily flash memory with serial access. The scenario is similar to that of a desktop computer, where the index would be stored on a hard drive, with a subset in RAM and the L2 cache. For an overview of the hierarchical nature of the memory architecture, see Fig. 1 and Table 1. The serial nature of the memory forces us to read and write single bits at a time in a page. A read operation takes 50 µ s. A write operation takes 1 ms, and may only alter a bit value of 1 to a bit value of 0. A sector, subsector or page may be erased in a single operation, filling it with 1-bits in approximately 500 ms. One important constraint is also that each page may typically only be erased a limited number of times (about 100 000), so it is crucial that our solution use the pages cyclically, rather than simply modifying the current ones in-place, to ensure wear leveling.

Based on general needs of a self-contained tolling system, and on the hardware capabilities just described, we derive the following set of requirements:

- A. The system must accommodate multiple versions of the same index structure at one time. The information may officially change at a given date, but the relevant data must be distributed to the units ahead of time.

- B. It must be possible to distribute new versions as incremental updates, rather than a full replacement. This is crucial in order to reduce communication costs and data transfer times. It will also make it less problematic to apply minor corrections to the database.

- C. The memory footprint must be low, as the memory available is highly limited.

- D. The database must maintain 100 % integrity, even during updates, to ensure uninterrupted access. It must be possible to roll back failed updates without affecting the current database.

- E. The indexing structure must be efficient in terms of CPU cycles during typical operations. Both available processing time and energy is highly limited and must not be wasted on, say, a linear scan over the data.

k

= 16

. . .

64

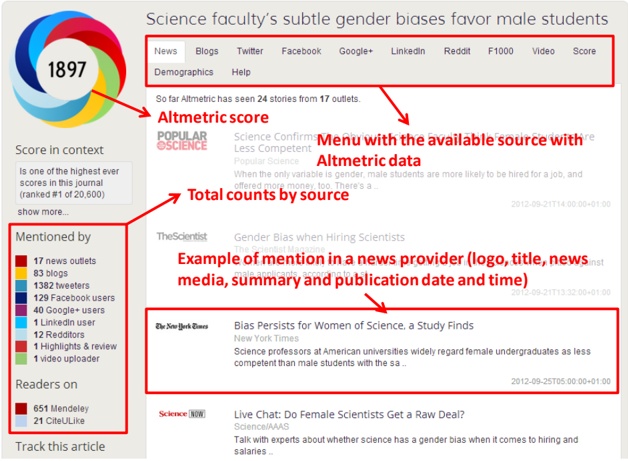

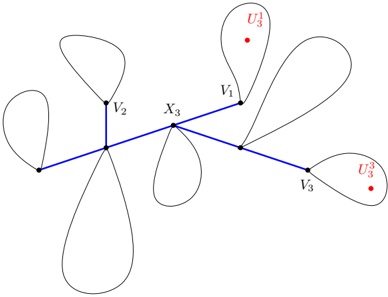

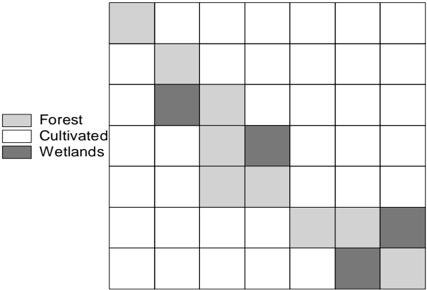

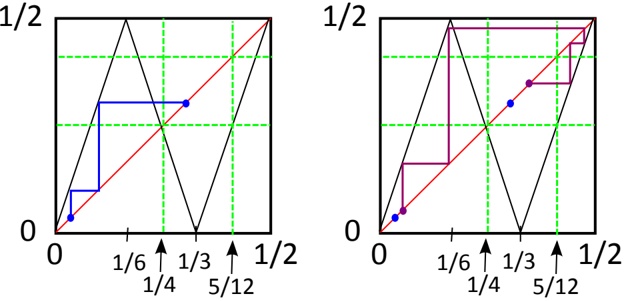

Figure 1: Flash memory architecture

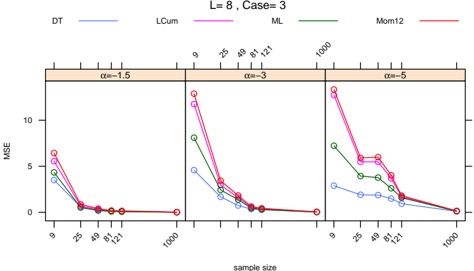

Table 1: Hierarchical memory architecture

| Description | Size | Access time | Persistent? |

|---------------------------|-----------------|----------------------|---------------|

| Processor internal memory | Ki-bytes | Zero wait state | No |

| External RAM | 100 KiB | Non-zero wait states | No |

| Serial Flash | 8, 16 or 32 MiB | See main text | Yes |

- F. The relevant data structure must minimize the number of flash page reads needed to perform typical operations, especially for search. Flash-page reads will be a limiting factor for some operations, so this is necessary to meet the real-time operation requirements.

- G. In order to avoid overloading individual pages (see discussion of memory architecture, above), wear leveling must be ensured through cyclic use.

- H. The typical operations that must be available under these constraints are basic two-dimensional geometric queries (finding nearby points or zones) as well as modification by adding and removing objects.

In addition, the system must accommodate multiple independent databases, such as tolling information for adjacent countries. Such databases can be downloaded on demand (e.g., when within a given distance of a border), cached, and deleted on a least-recently-used basis, for example. We do not address this directly as a requirement, as it is covered by the need for a low memory footprint per database (Req. C).

As in most substantial lists of requirements, there are obvious synergies between some (e.g., Reqs. E and F) while some are orthogonal and some seem to be in direct opposition to each other (e.g., Reqs. A and C). In Section 3, we describe a simple index structure that allows us to satisfy all our requirements to a satisfactory degree.

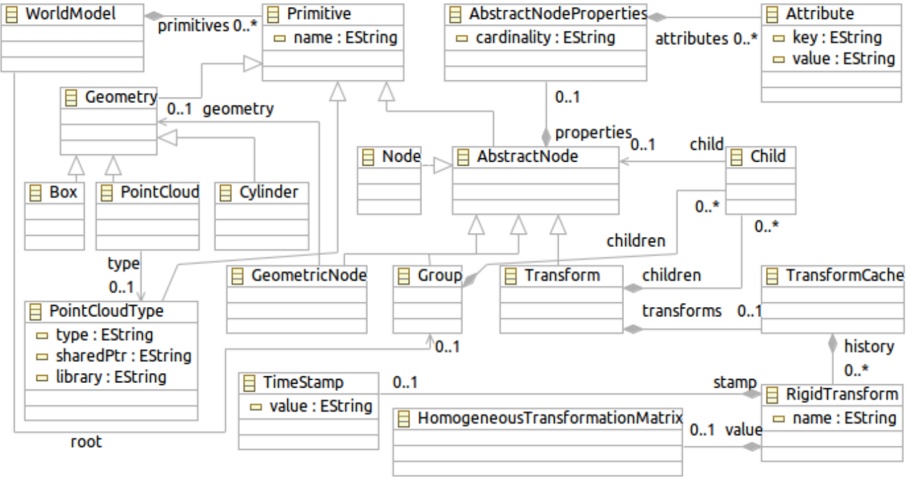

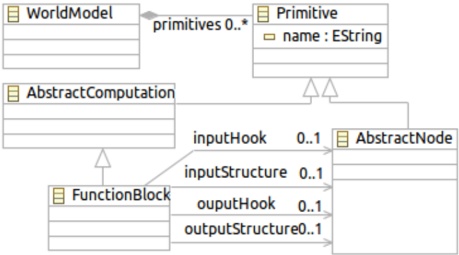

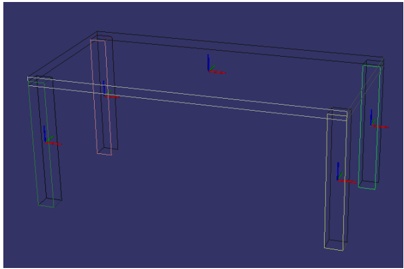

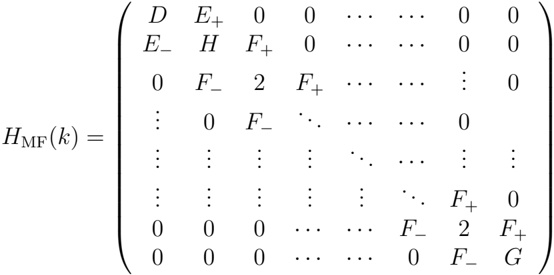

## 3 Our Solution: Immutable 9-by-9 Quadtrees

The solution to the indexing problem lies in combining two well-known technologies: quadtrees and immutable data structures.

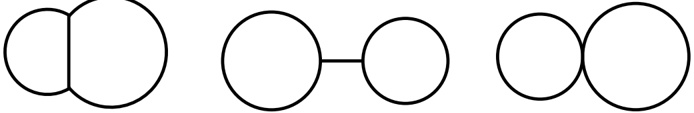

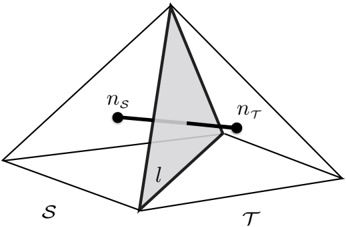

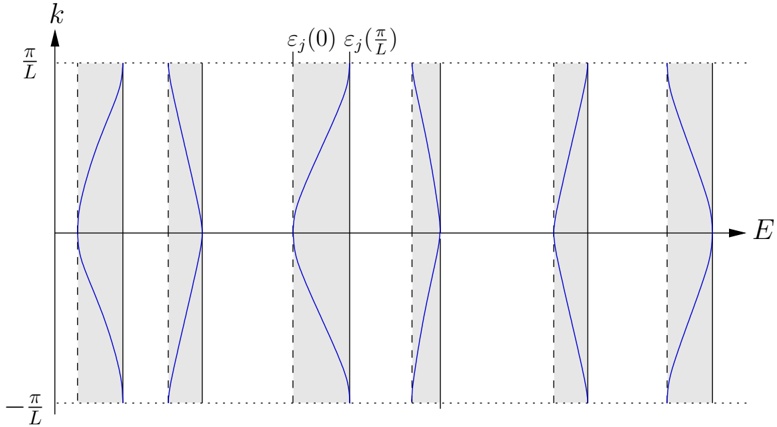

In the field of geographic and geometric databases, one of the simplest and most well-known data structures is the quadtree, which is a two-dimensional extension of the basic binary search tree. Just as a binary search tree partitions R into two halves, recursively, the quadtree partitions R 2 into quadrants. A difference between the two is that where the binary search tree splits based on keys in the data set, the quadtree computes its quadrants from the geometry of the space itself. ∗ In order to reduce the number of node (i.e., page) accesses, at the expense of more coordinate computations, we increase the grid of our tree from 2-by-2 to 9-by-9. The specific choice of this grid size is motivated by the constraints of the system. We need 3 bytes to address a flash page and with a 9-by-9 grid, we can fit one node into 9 · 9 · 3 = 243 bytes, which permits us to fit one node (along with some book-keeping data) into a 256 B flash page. This gives us a very shallow tree, with a fanout of 81, which reduces the number of flash page accesses considerably. For an example

∗ Technically, this is the form of quadtrees known as PR Quadtrees [5, § 1.4.2.2].

of the resulting node sizes (area of ground covered), see Table 2. The last three columns show the number of leaf nodes at the various levels in the experimental build described in Section 4.

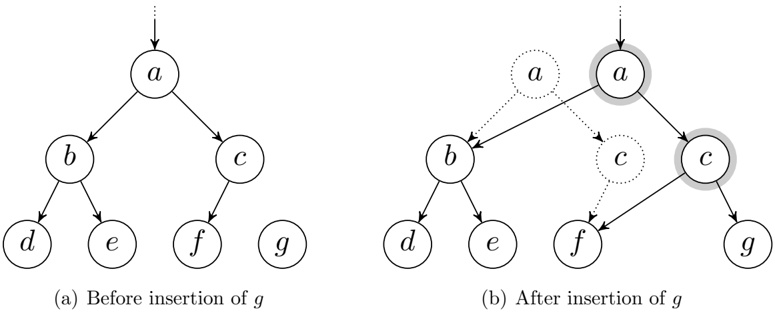

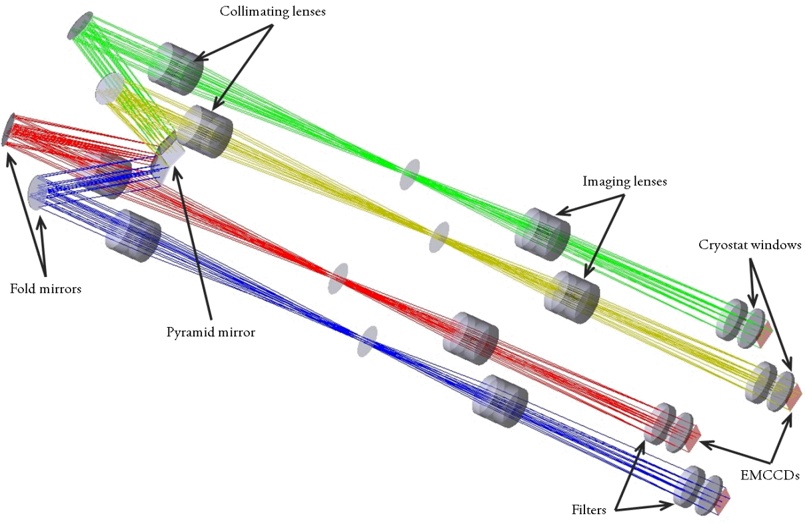

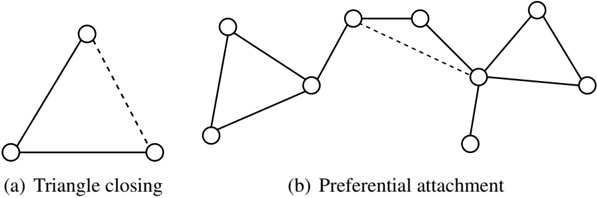

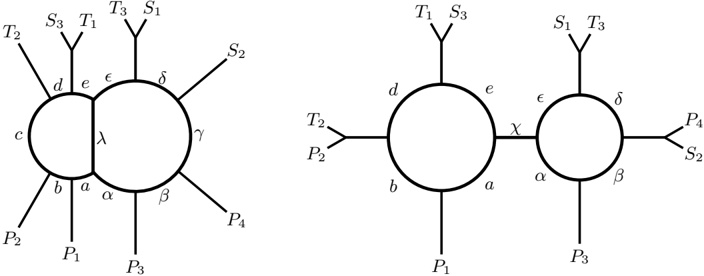

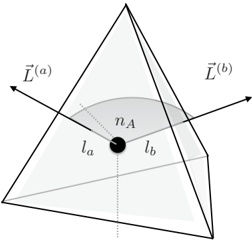

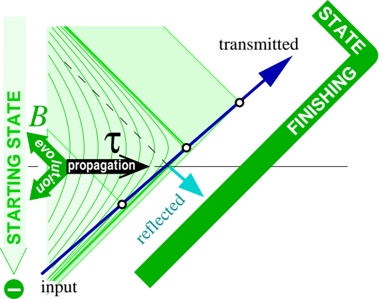

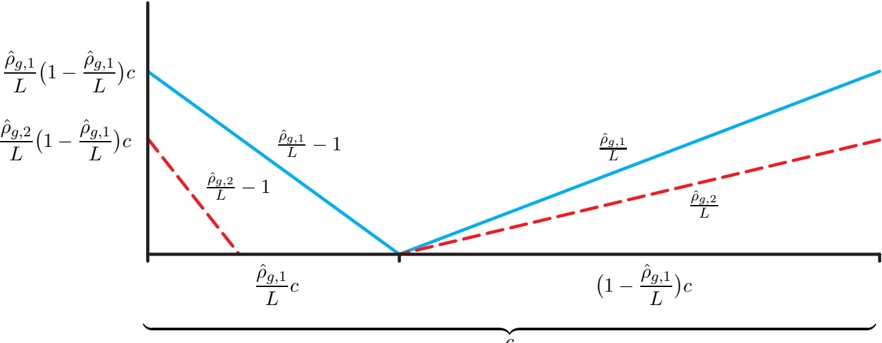

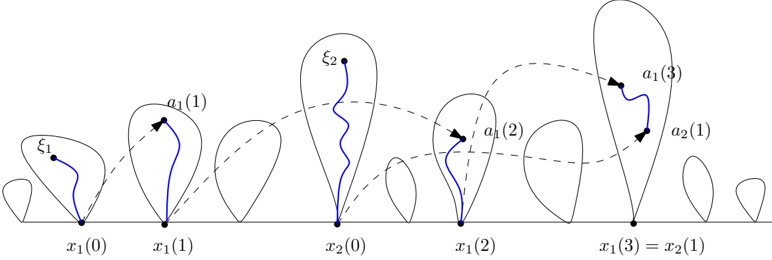

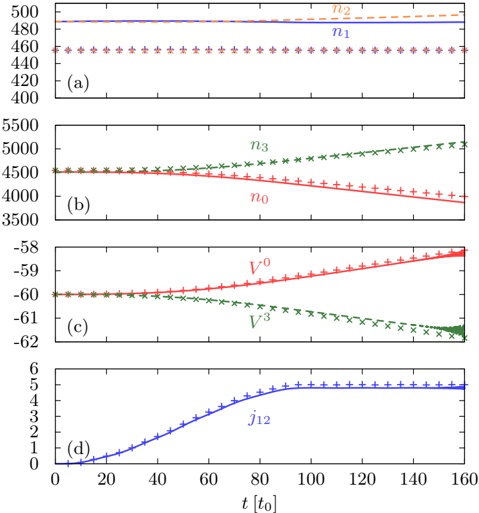

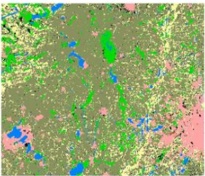

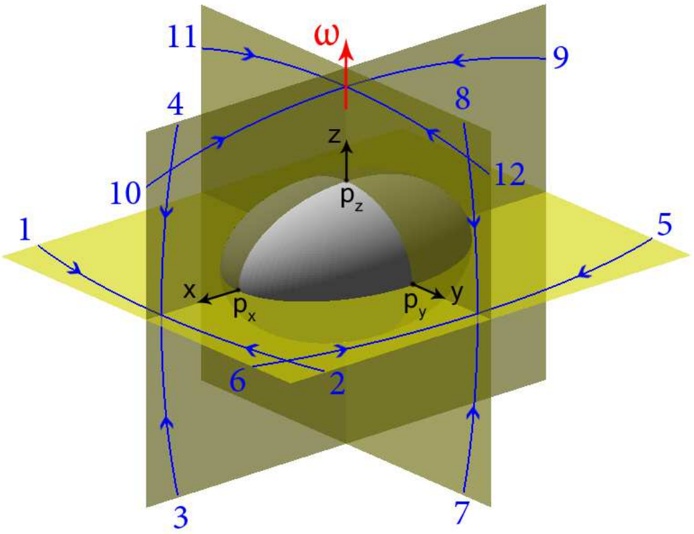

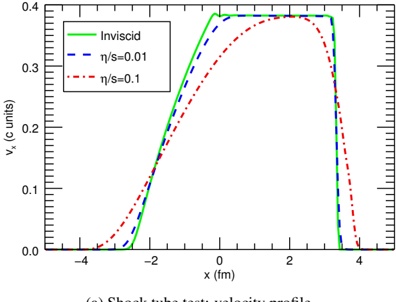

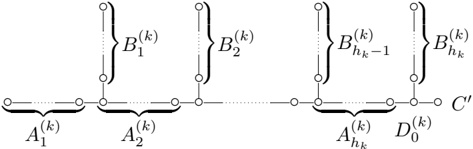

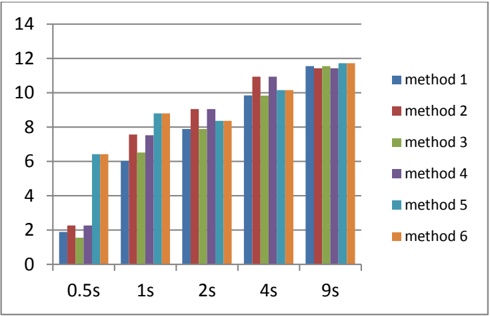

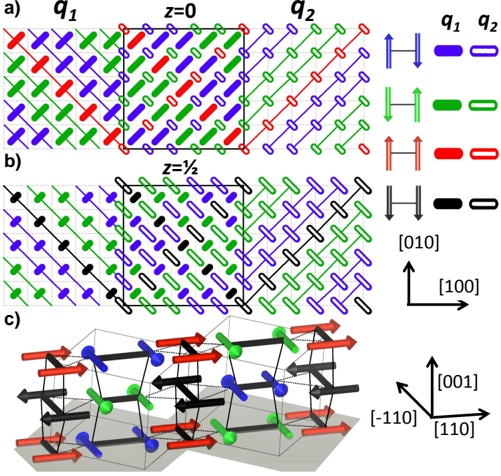

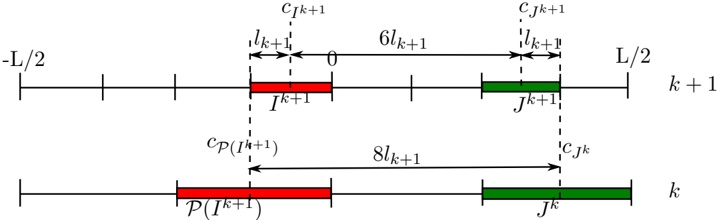

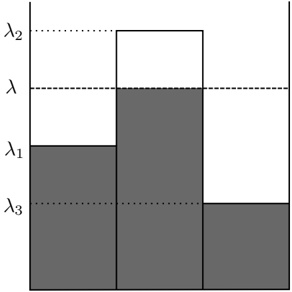

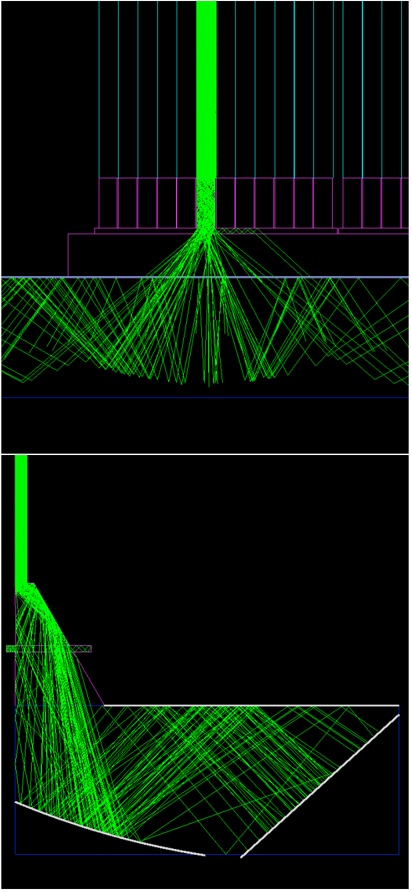

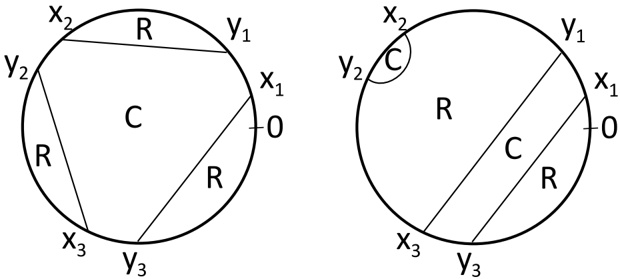

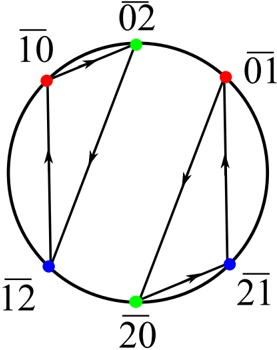

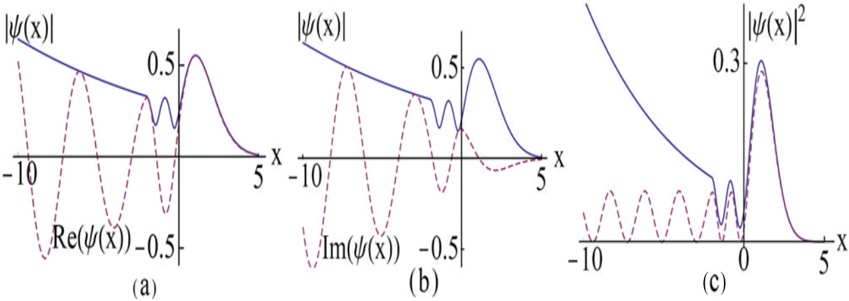

Immutable data structures have been used in purely functional programming for decades [see, e.g., 6], and they have recently become more well known to the mainstream programming community through the data model used in, for example, the Git version control system [see, e.g., 7, p. 3]. The main idea is that instead of modifying a data structure in place, any nodes that would be affected by the modification are duplicated. For a tree structure, this generally means the ancestor nodes of the one that is, say, added. Consider the example in Fig. 2. In Fig. 2(a), we see a tree consisting of nodes a through f , and we are about to insert g . Rather than adding a child to c , which is not permitted, we duplicate the path up to the root, with the duplicated nodes getting the appropriate child-pointers, as shown in Fig.2(b), where the duplicated nodes are highlighted. As can be seen, the old nodes (dotted) are still there, and if we treat the old a as the root, we still have access to the entire previous version of the tree.

## 4 Experimental Evaluation

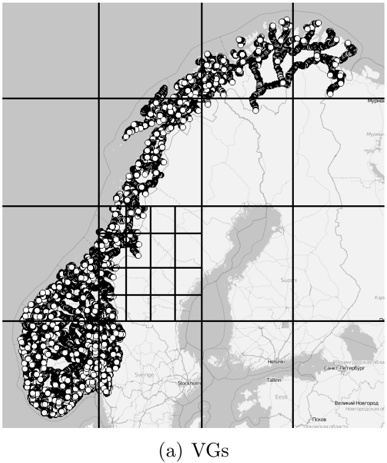

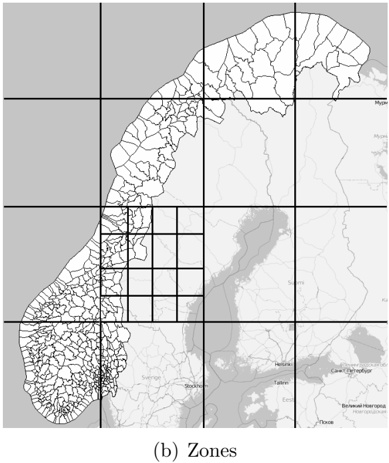

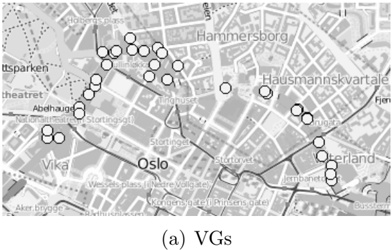

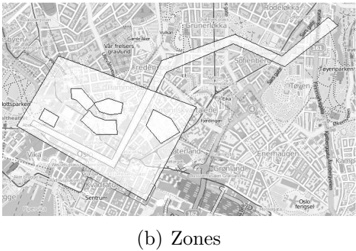

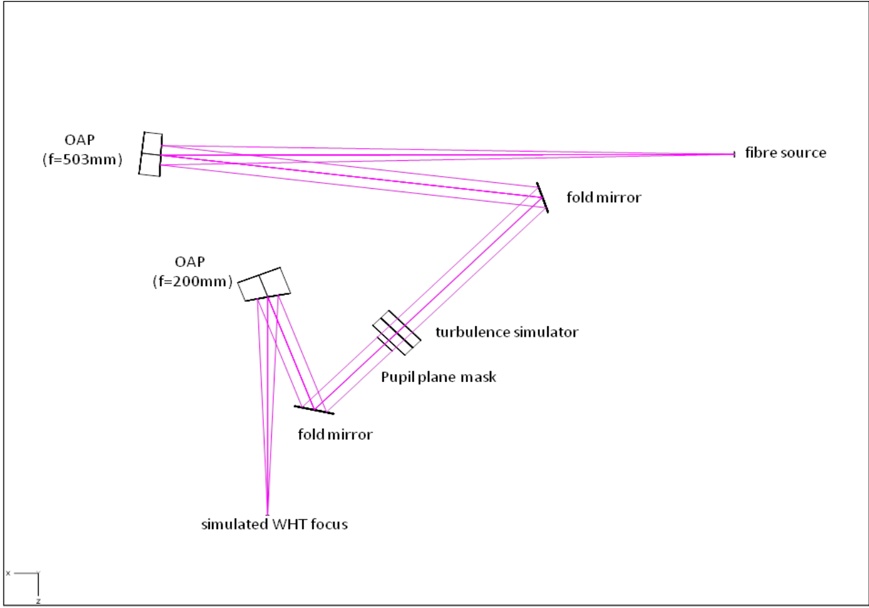

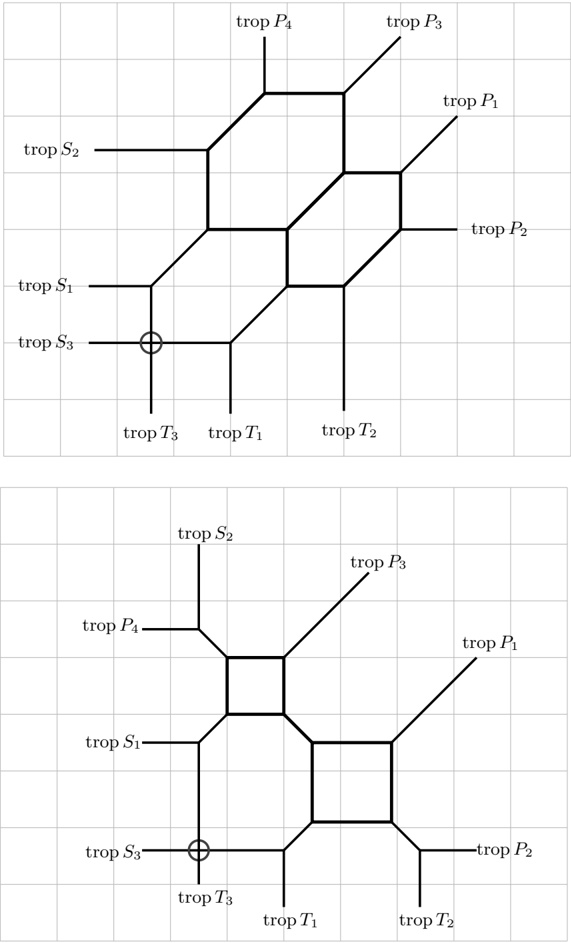

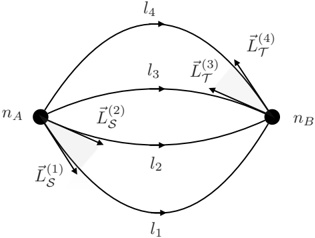

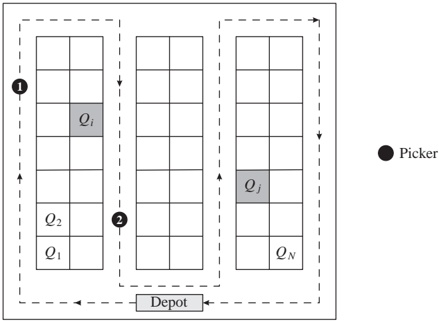

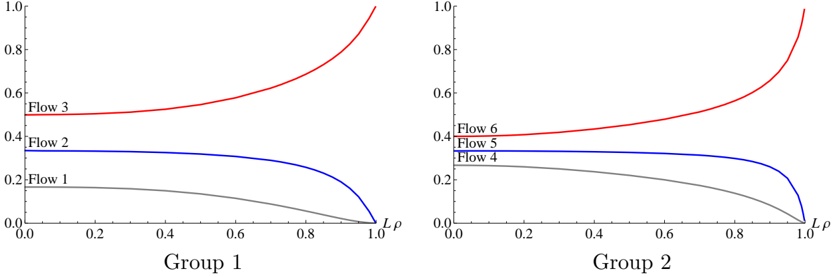

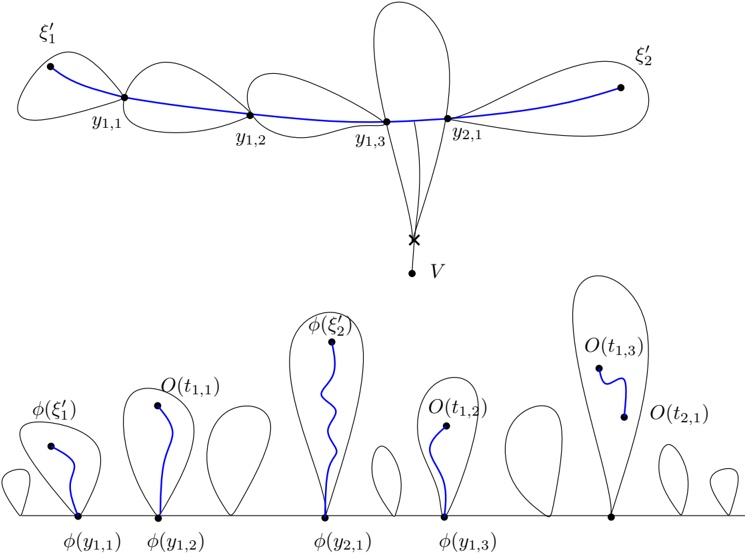

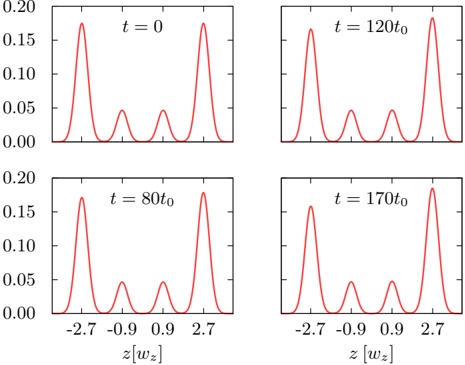

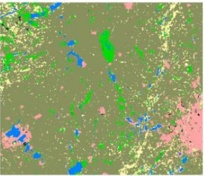

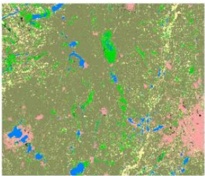

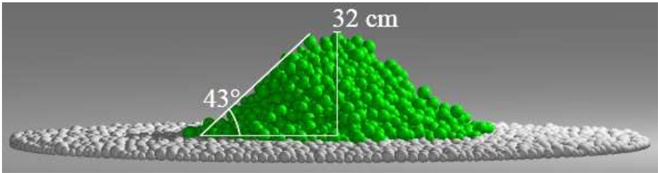

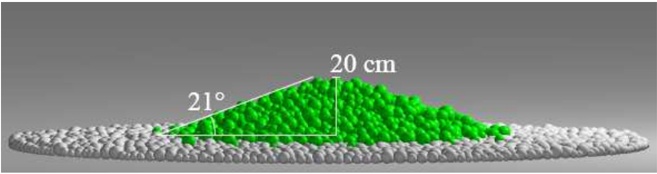

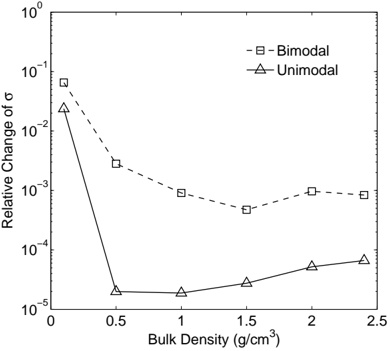

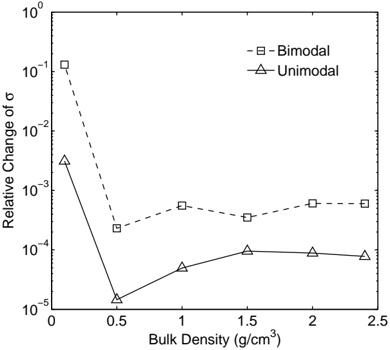

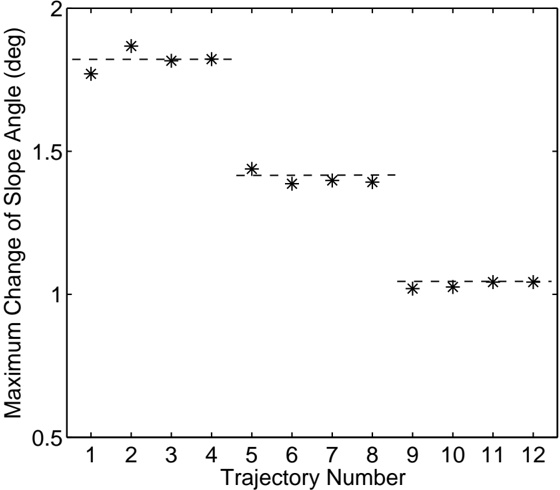

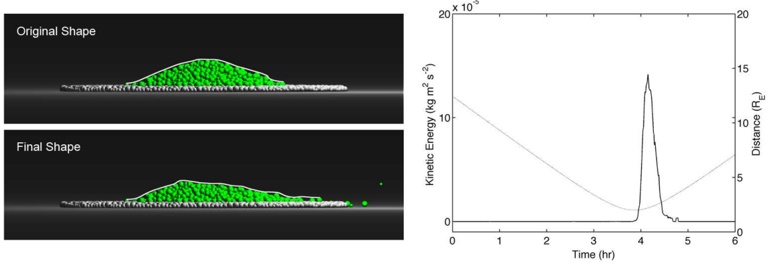

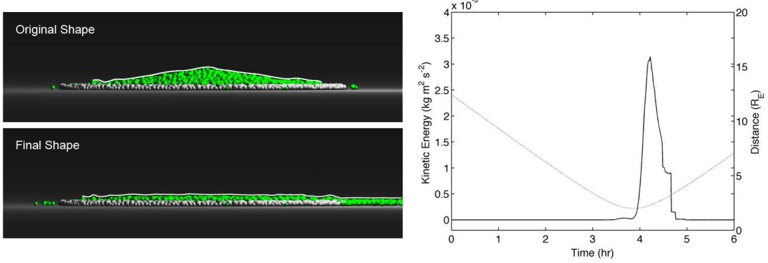

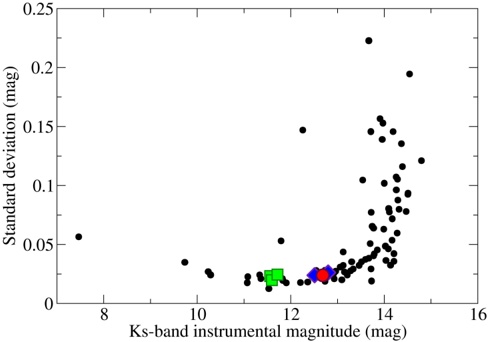

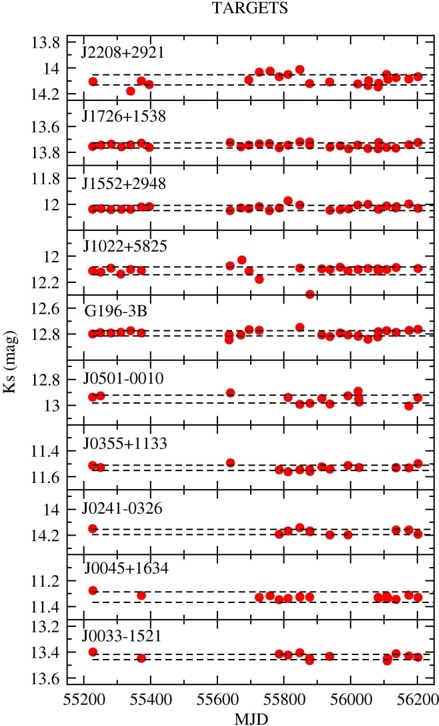

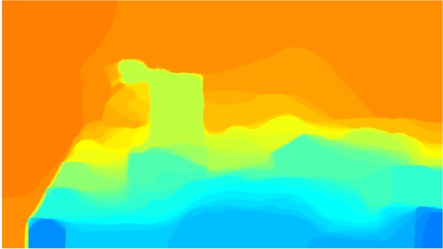

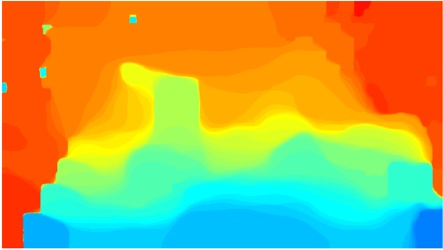

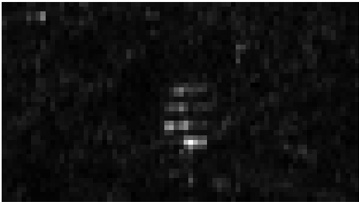

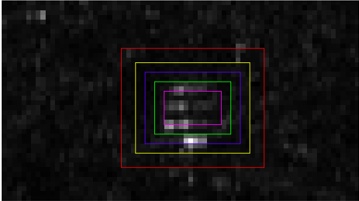

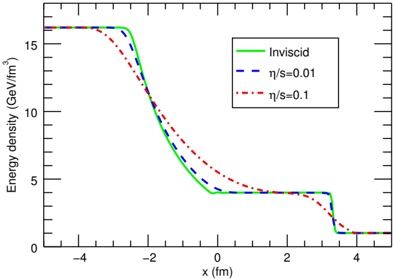

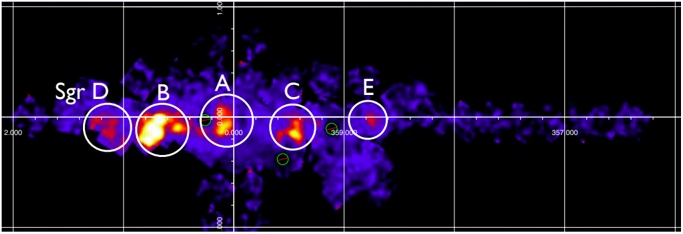

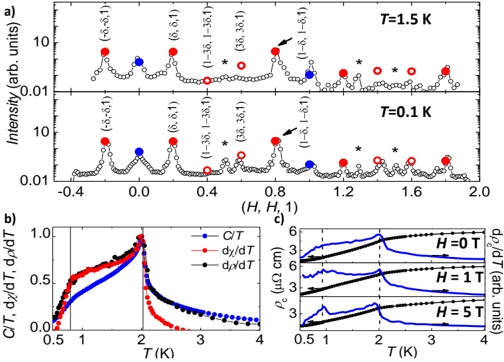

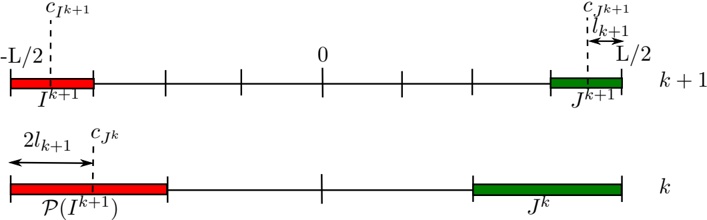

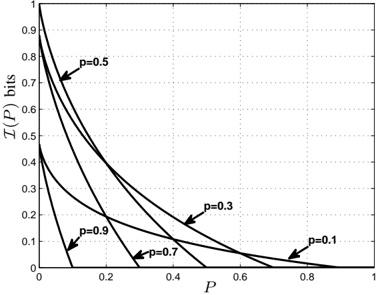

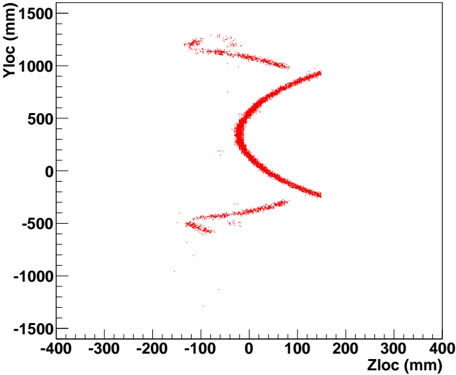

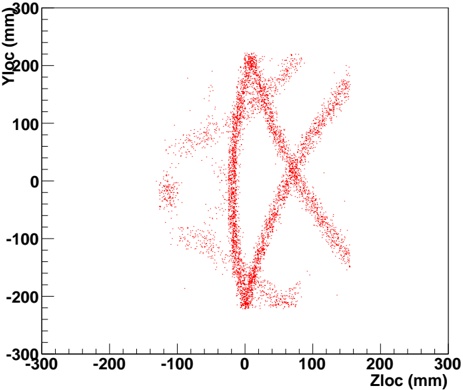

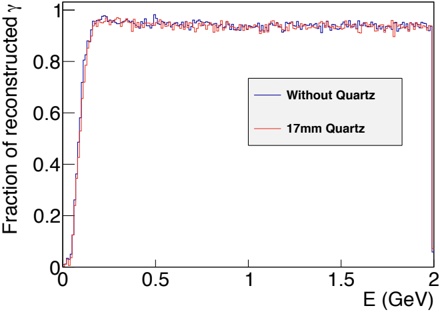

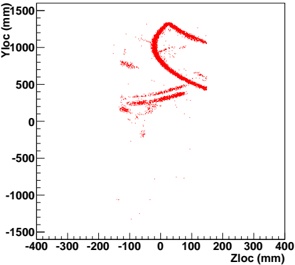

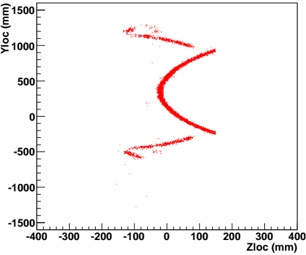

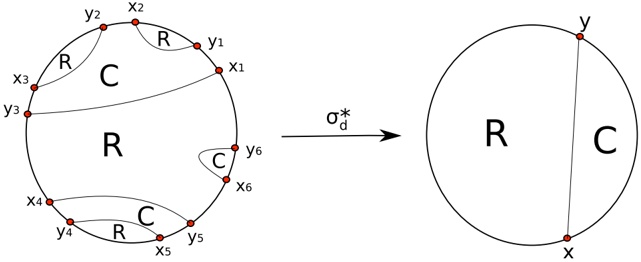

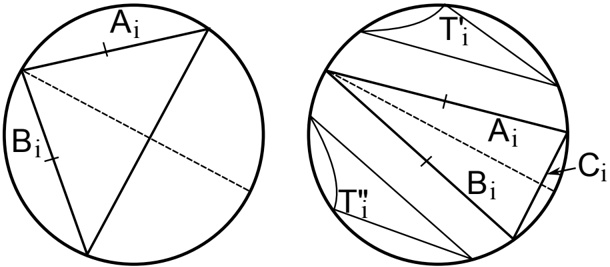

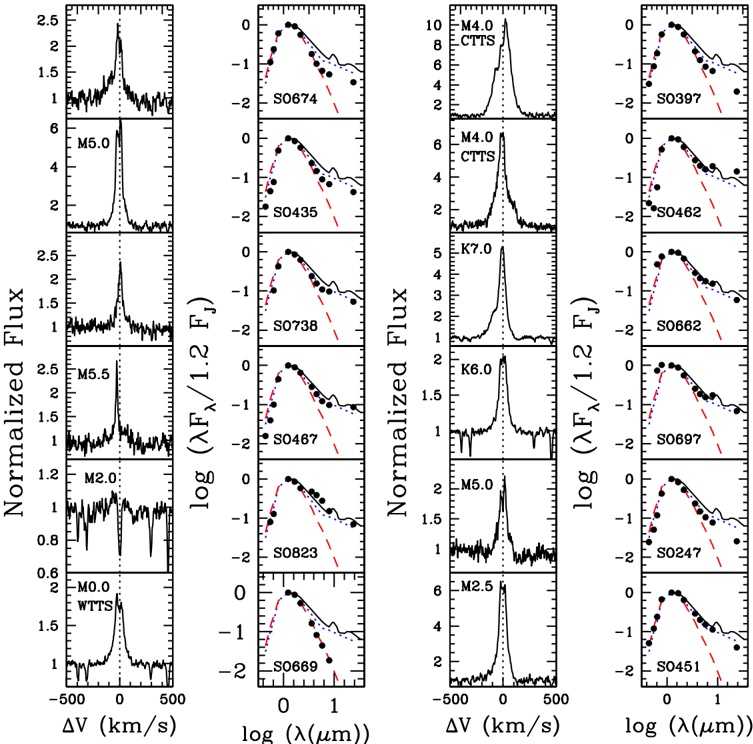

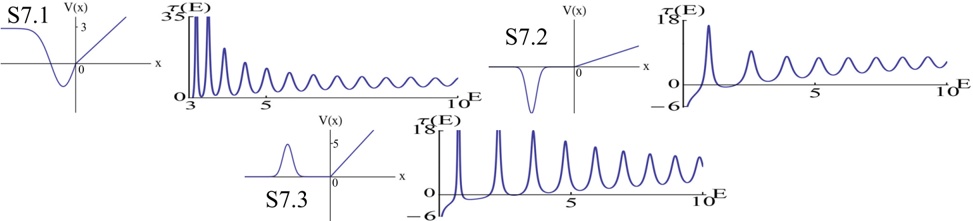

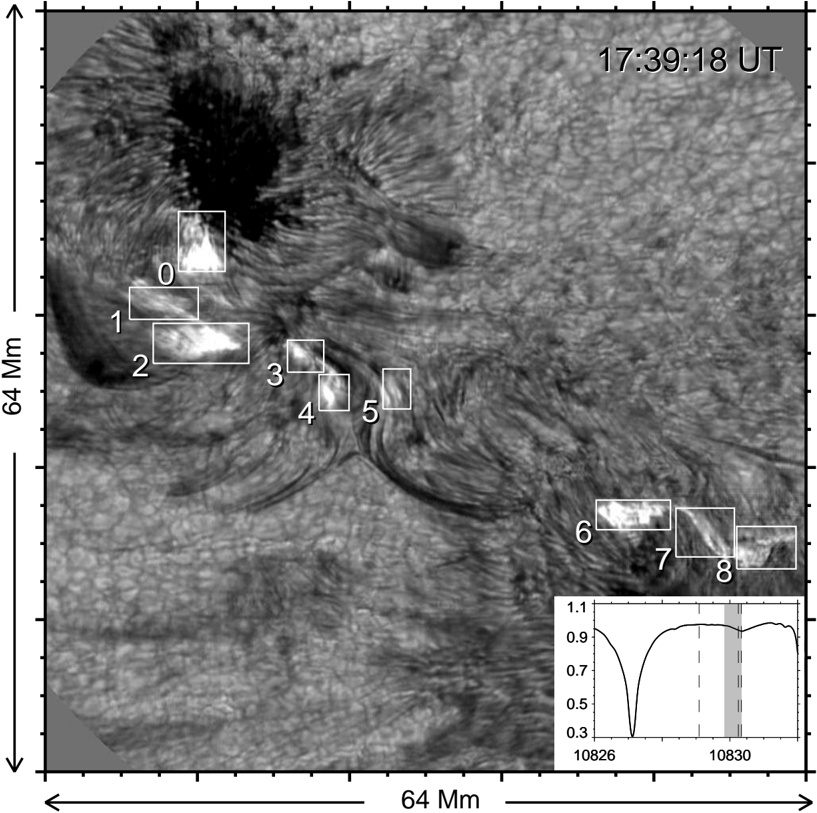

Our experiments were performed with a data set of approximately 30 000 virtual gantries (see Fig. 3(a)), generated from publicly available maps [8]. The maps describe the main roads of Norway with limited accuracy. Additionally, more detailed and accurate virtual gantries were created manually for some locations in Oslo and Trondheim. Fig. 4(a) shows the relevant virtual gantries in downtown Oslo, used in our test drive. There are about 35 virtual gantries on this route, and many of these are very close together. In general, there is one virtual gantry before every intersection.

Each local administrative unit ( kommune ) is present in the maps used [8], with fairly accurate and detailed boundaries. There are 446 such zones in total (see Fig. 3(b)). In addition, more detailed and accurate zones were created manually for some locations in the cities of Oslo and Trondheim. Some of these are quite small, very close together, and partially overlapping (see Fig. 4(b)).

## Data Structure Build

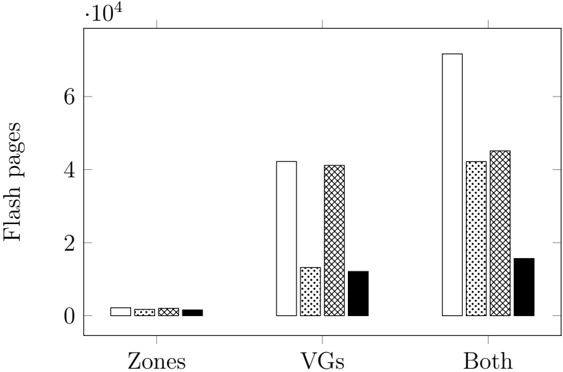

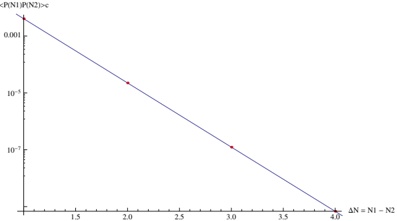

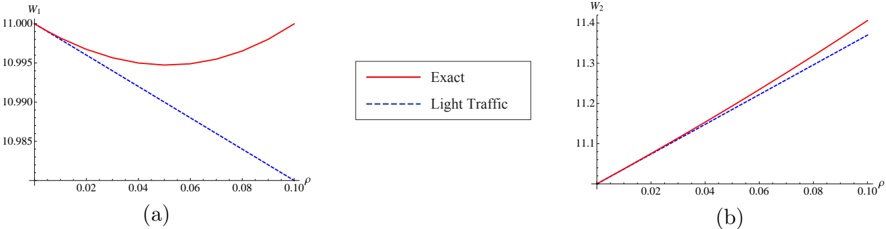

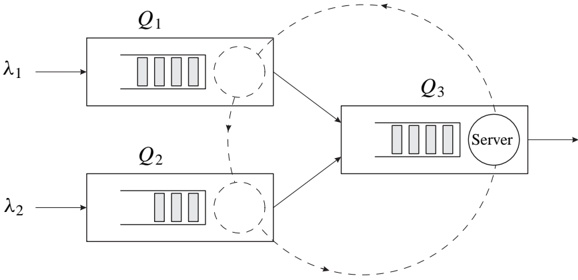

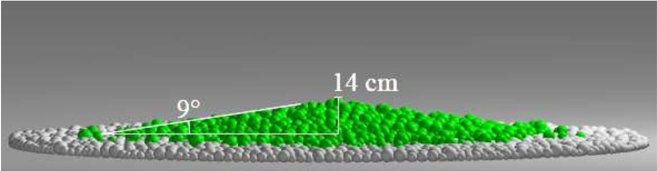

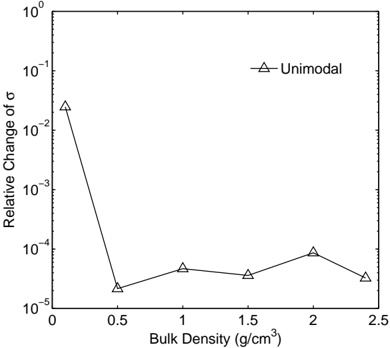

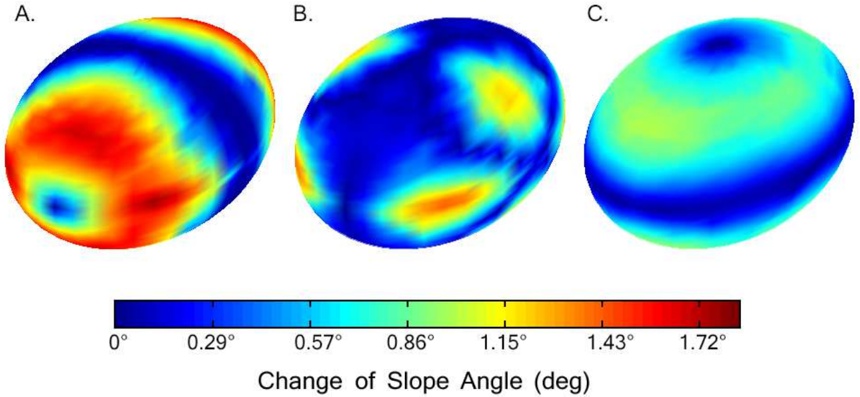

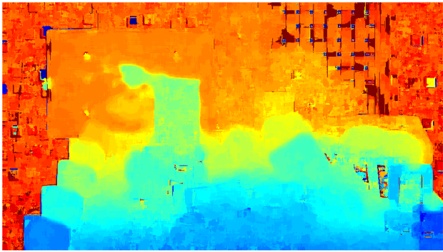

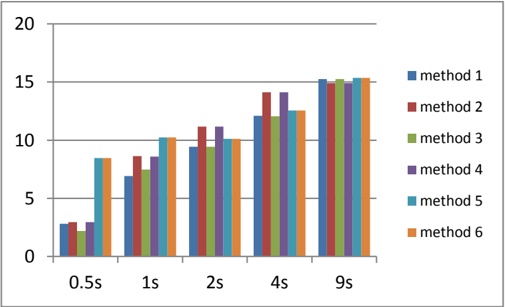

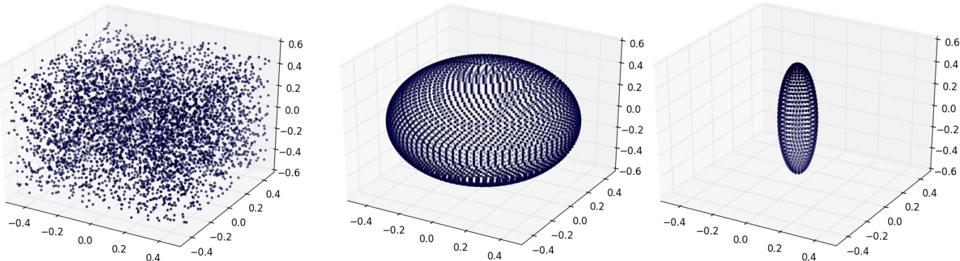

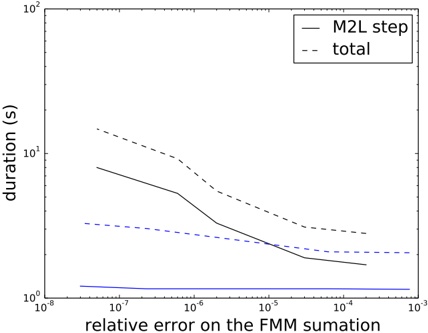

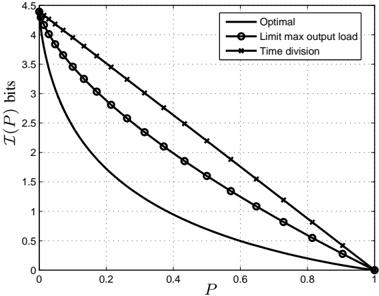

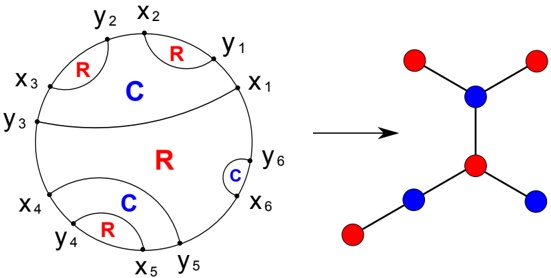

These test data were inserted into the quadtree as described in Section 3. Table 3 summarizes the important statistics of the resulting structure. The numbers for memory usage are also shown in Fig. 5, for easier comparison.

Table 2: Tree levels. Sizes are approximate

| Level | Size | Zone | VG | Both |

|---------|----------------|--------|--------|--------|

| Top | 2 . 0 × 10 6 m | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 2 . 1 × 10 5 m | 15 | 0 | 4 |

| 2 | 2 . 4 × 10 4 m | 625 | 168 | 471 |

| 3 | 2 . 5 × 10 3 m | 81 | 12 353 | 39 721 |

| 4 | 3 . 0 × 10 2 m | 0 | 157 | 486 |

| 5 | 3 . 0 × 10 1 m | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Figure 2: Node g is inserted by creating new versions of node a and c (highlighted), leaving the old ones (dotted) in place

Figure 3: Virtual gantries and zones of Norway, with an illustrative quadtree grid

Figure 4: Virtual gantries and overlapping zones in downtown Oslo

Table 3: Tree performance numbers

| | Description | Zones | VGs | Both |

|----|-----------------------------------|---------|---------|---------|

| a | Number of objects in database | 448 | 29 037 | 29 485 |

| b | Flash pages for index and data | 2164 | 42 217 | 71 675 |

| c | Size (MiB) | 0 . 53 | 10 . 31 | 17 . 50 |

| d | Flash pages for index | 1716 | 13 180 | 42 190 |

| e | Objects referenced by leafs | 2481 | 43 263 | 95 272 |

| f | Leaf nodes per object | 5 . 5 | 1 . 5 | 115 |

| g | Leaf entries not used, empty | 240 | 27 403 | 1319 |

| h | Leaf entries set | 733 | 13 179 | 41 207 |

| i | Max index tree depth | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| j | Zone inside entries | 57 | | 30 379 |

| k | Zone edge entries | 2406 | | 21 333 |

| l | Distinct leaf pages | 578 | 11 608 | 14 138 |

| m | Total leaf pages | 721 | 12 678 | 40 682 |

| n | Duplicate leaf pages | 143 | 1070 | 26 544 |

| o | Flash pages, dups removed | 2021 | 41 147 | 45 131 |

| p | Size, dups removed (MiB) | 0 . 49 | 10 . 05 | 11 . 02 |

| q | Index pages, dups removed | 1573 | 12 110 | 15 646 |

| r | Size of index, dups removed (MiB) | 0 . 38 | 2 . 96 | 3 . 82 |

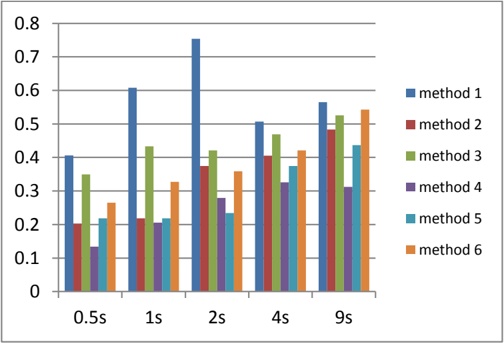

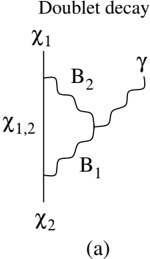

Figure 5: The plot shows total flash pages used ( ) and flash pages used for the index ( ), as well as the same with duplicates removed ( and , respectively) for a data base consisting of zones, virtual gantries, or both (c.f., Table 3)

Judging from these numbers (row r ), a database containing only zones would be quite small (about 0 38 MiB). . Each zone is referenced by 5 5 leaf nodes on average . (row f ). Also note that only 57 leaf nodes (squares) are entirely contained in a zone (row j ). This implies that the geometric inside/outside calculations will need to be computed in most cases.

This can be contrasted with the combined database of gantries and zones. The index is larger (3 82 MiB, row . r ), but the performance of polygon assessments is much better. Each polygon is referenced from 115 leaf nodes (row f ) and there are more inside entries than edge entries (30 379 vs 21 333). This indicates that the geometric computations will be needed much less frequently.

Each of the three scenarios creates a number of duplicate leaf pages. Many leaf pages will contain the same zone edge/inside information. In our implementation of the algorithm, this issue is not addressed or optimized. It is, however, quite easy to introduce a reference-counting scheme or the like to eliminate duplicates, in this scenario saving 6 MiB (as shown in rows o through r ).

The zone database contains very few empty leaf entries (row g ), because the union of the regions covers the entire country, with empty regions found in the sea or in neighboring countries.

## Flash Access in a Real-World Scenario

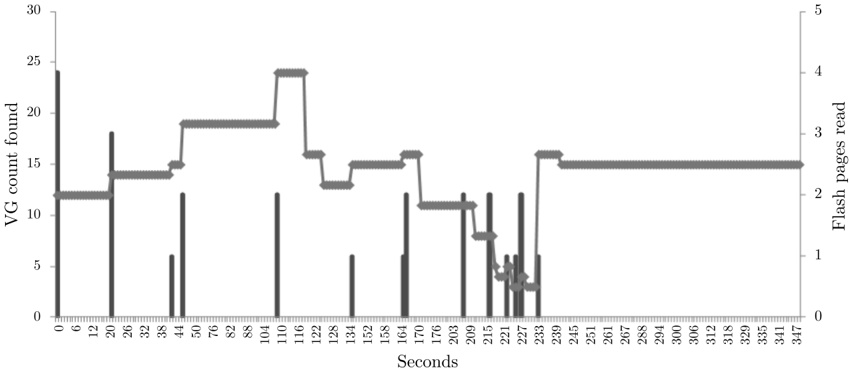

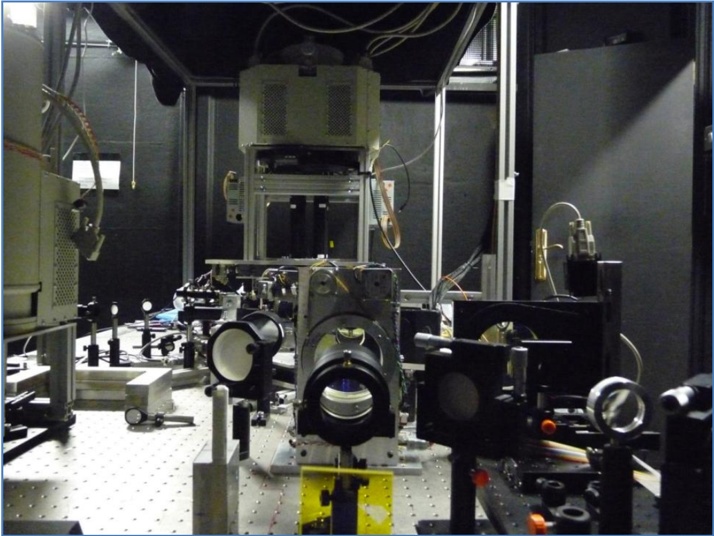

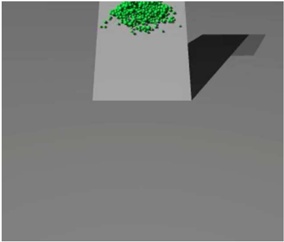

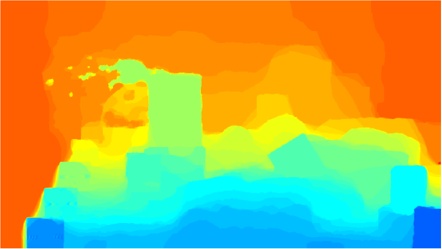

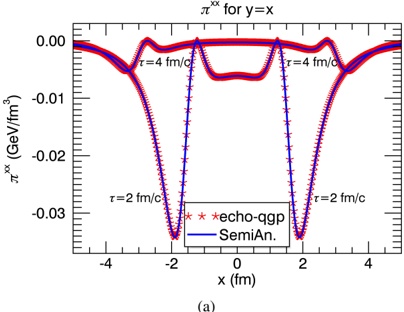

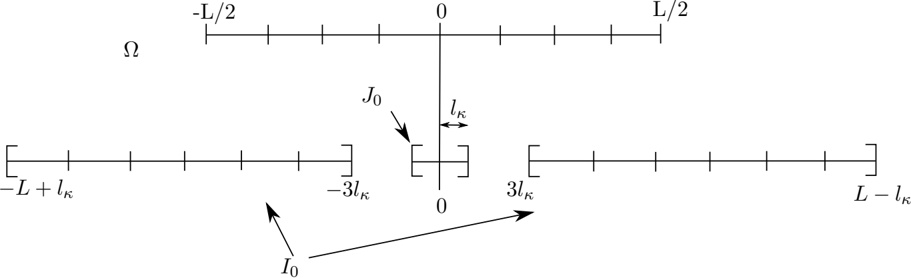

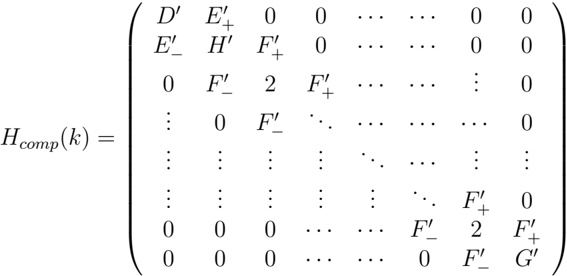

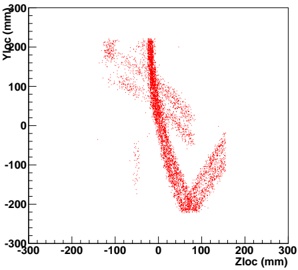

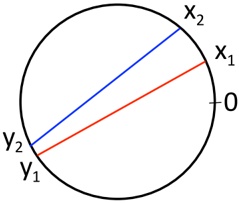

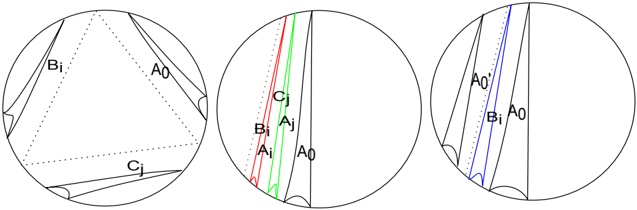

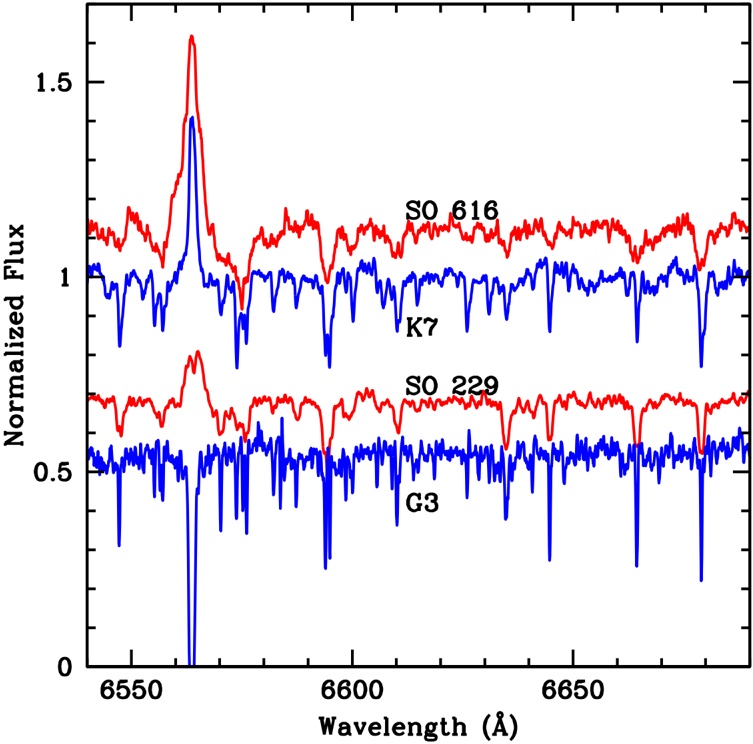

The index was also tested in a 2 km drive, eastbound on Ibsenringen, in downtown Oslo. The relevant virtual gantries are shown in the map in Fig. 4(a). The inmemory flash cache used was 15 pages (15 · 256 B), and the cache was invalidated before test start. Fig. 6 shows the result, in terms of flash accesses and the number of gantries found.

## 5 Discussion

To view our results in the context of the initial problem, we revisit our requirement list from Section 2. We can break our solution into three main features: ( i ) The use of quadtrees for indexing; ( ii ) purely functional updates and immutability; and ( iii ) high fanout, with a 9-by-9 grid. Table 4 summarizes how these features, taken together, satisfy all our requirements. Each feature is either partly or fully relevant for any requirement it helps satisfy (indicated by ◦ or · , respectively).

Our starting-point is the need for spatial (two-dimensional) indexing (Req. H), and a desire for simplicity in our solution. The slowness of our hardware made a straightforward linear scan impossible, even with a data set of limited size. This led us to the use of quadtrees, whose primary function, seen in isolation, is satisfying Req. E, CPU efficiency. It also supports Req. C (low memory footprint) by giving us a platform for reducing duplication. Lastly, it supports efficiency in terms of flash page accesses (Req. F), which is primarily handled by high fanout, using the nine-by-nine grid.

The purely functional updates, and the immutable nature of our structure, satisfies a slew of requirements by itself. Just as in modern version control systems such as Git [7], immutable tree structures where subtrees are shared between versions gives us a highly space-efficient way of distributing and storing multiple, incremental versions of the database (Reqs. A to C). This also gives us the ability to keep using the database during an update, and to roll back the update if an error occurs,

Figure 6: Flash access in an actual drive (Oslo Ring-1 Eastbound): flash pages read (vertical bars) and virtual gantries found (horizontal lines)

without any impact on the database use, as the original database is not modified (Req. D). Finally, because modifications will always use new flash pages, we avoid excessive modifiations of, say, the root node, and can schedule the list of free nodes to attain a high degree of wear leveling (Req. G).

In our tests, as discussed in the previous section, we found that the solution satisfied our requirements not only conceptually, but also in actual operation. It can contain real-world data within real-world memory constraints (Table 3), and can serve up results in real time during actual operation, with relatively low flash access rates (Fig. 6).

## 6 Conclusion & Future Work

We have described the problem of real-time spatial indexing in an in-vehicle satellite navigation ( gnss ) unit for the purposes of open-road tolling. From this problem we have elaborated a set of performance and functionality requirements. These requirements include issues that are not commonly found in indexing for ordinary computers, such as the need for wear-leveling over memory locations. By modifying the widely used quadtree data structure to use a higher fanout, and by making it immutable, using purely functional updates, we were able to satisfy our entire list of requirements. We also tested the solution empirically, on real-world data and in a real-world context of a vehicle run, and found that it performed satisfactorily.

Although our object of focus has been a rather limited family of hardware

Table 4: How components of the solution satisfy various requirements

| Feature | A | B | C | D | E | F | H |

|--------------------------------------------|-----|-----|-----|-----|-----|-----|-----|

| The use of quadtrees for indexing | | | ◦ | | • | ◦ | • |

| Purely functional updates and immutability | • | • | • | • | | | • |

| High fanout, with 9-by-9 grid | | | | | | • | |

architectures, the simple, basic ideas of our index chould be useful also for other devices and applications where real-time spatial indexing is required under somewhat similar flash memory conditions. Possible extensions of our work could be to test the method under different conditions, perhaps by developing a simulator for in-vehicle units with different architectures and parameters. This could be useful for choosing among different hardware solutions, as well as for tuning the index structure and database.

Disclaimer & Acknowledgements Magnus Lie Hetland introduced the main design idea of using immutable, high-fanout quadtrees for the database structure. He wrote the majority of the text of the current paper, based in large part on the technical report of Lykkja [4]. Ola Martin Lykkja implemented and benchmarked the database structure and documented the experiments [4]. Neither author declares any conflicts of interest. Both authors have revised the paper and approved the final version. The authors would like to thank Hans Christian Bolstad for fruitful discussions on the topic of the paper. This work has in part been financed by the Norwegian Research Council (BIA project no. 210545, 'SAVE').

## References

- [1] Frank Kelly. Road pricing: addressing congestion, pollution and the financing of britain's roads. Ingenia , 29:34-40, December 2006.

- [2] Peter Hills and Phil Blythe. For whom the road tolls? Ingenia , 14:21-28, November 2002.

- [3] Bern Grush. Road tolling isn't navigation. European Journal of Navigation , 6 (1), February 2008.

- [4] Ola Martin Lykkja. SAVE tolling objects database design. Technical Report QFR01-207-1492 0.7, Q-Free ASA, Trondheim, Norway, 2012.

- [5] Hanan Samet. Foundations of Multidimensional and Metric Data Structures . Morgan Kaufmann, 2006.

- [6] Chris Okasaki. Purely Functional Data Structures . Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- [7] Jon Loeliger and Matthew McCullough. Version Control with Git . O'Reilly, second edition, 2012.

- [8] Kartverket. N2000 kartdata. Available from http://www.kartverket.no/Kart/ Kartdata/Vektorkart/N2000 , 2012. | null | [

"Magnus Lie Hetland",

"Ola Martin Lykkja"

] | 2014-08-01T09:42:45+00:00 | 2014-08-01T09:42:45+00:00 | [

"cs.DS"

] | A Real-Time Spatial Index for In-Vehicle Units | We construct a spatial indexing solution for the highly constrained

environment of an in-vehicle unit in a distributed vehicle tolling scheme based

on satellite navigation (GNSS). We show that an immutable, purely functional

implementation of a high-fanout quadtree is a simple, practical solution that

satisfies all the requirements of such a system. |

1408.0115v1 | ## Gauge-covariant extensions of Killing tensors and conservation laws

J.W. van Holten a

## Nikhef

Science Park 105, Amsterdam NL

and

Lorentz Institute, Leiden University

Niels Bohrweg 2, Leiden NL

## Abstract

In classical and quantum mechanical systems on manifolds with gauge-field fluxes, constants of motion are constructed from gauge-covariant extensions of Killing vectors and tensors. This construction can be carried out using a manifestly covariant procedure, in terms of covariant phase space with a covariant generalization of the Poisson brackets, c.q. quantum commutators. Some examples of this construction are presented.

a e-mail: [email protected]

## 1 Noether's theorem

This paper discusses symmetries and conservation laws in the context of hamiltonian dynamics. The discussion is framed predominantly in the language of classical dynamics, but the use of Poisson brackets and their correspondence with quantum commutators, guarantees that many results also apply to the operator formulation of quantum dynamics. The main difference is the operator ordering to be implemented in quantum theory, the technicalities of which are not relevant to the issues I focus on.

The connection between continuous symmetries and conservation laws is established by Noether's theorem [1]. I briefly review the theorem by considering infinitesimal transformations on phase-space variables ( x, p ) obtained from a generating function G x, p ( ) through the Poisson brackets

$$\delta x = \{ x, G \} = \frac { \partial G } { \partial p }, \quad \delta G = \{ p, G \} = - \frac { \partial G } { \partial x }.$$

Observe, that these variations are defined such that G itself is an invariant:

$$\delta G = \delta x \frac { \partial G } { \partial x } + \delta p \frac { \partial G } { \partial p } = \{ G, G \} = 0.$$

Under such transformations the hamiltonian of the system changes by

$$\delta H = \{ H, G \} = - \frac { d G } { d t },$$

the change of G along the phase-space trajectory ( x t , p ( ) ( )) t generated by the hamiltonian H . It follows immediately, that G is a constant of motion if the hamiltonian is invariant under the transformations (1).

It is also of some interest to consider the variation of the action

$$S = \int _ { 1 } ^ { 2 } d t \left ( p \, \frac { d x } { d t } - H ( x, p ) \right ).$$

Applying the variations (1)

$$\delta S = \int _ { 1 } ^ { 2 } d t \left [ \frac { d } { d t } \left ( p \, \frac { \partial G } { \partial p } - G \right ) - \{ H, G \} \right ] = \left [ p \frac { \partial G } { \partial p } - G \right ] _ { 1 } ^ { 2 }.$$

Thus variations under which the hamiltonian is invariant, leave the action invariant modulo boundary terms. This is sufficient for G to be a constant of motion.

## 2 Isometries of manifolds

On a manifold with (local) co-ordinates x µ and metric g µν ( x ) the geodesics can be obtained as the trajectories of test-particles with proper-time hamiltonian

$$H = \frac { 1 } { 2 } \, g ^ { \mu \nu } p _ { \mu } p _ { \nu }.$$

Indeed, using the overdot notation for proper-time derivatives, the hamilton equations take the form

$$\dot { x } ^ { \mu } = g ^ { \mu \nu } p _ { \nu }, \quad \dot { p } _ { \mu } = - \frac { 1 } { 2 } \, \frac { \partial g ^ { \nu \lambda } } { \partial x ^ { \mu } } \, p _ { \nu } p _ { \lambda } = \frac { 1 } { 2 } \, \frac { \partial g _ { \nu \lambda } } { \partial x ^ { \mu } } \, \dot { x } ^ { \nu } \dot { x } ^ { \lambda }.$$

The last expression is equivalent to the geodesic equation

$$\ddot { x } ^ { \mu } + \Gamma _ { \lambda \nu } ^ { \ \mu } \, \dot { x } ^ { \lambda } \dot { x } ^ { \nu } = 0.$$

In this language, isometries of the manifold are found as constants of motion which are linear in the momentum:

$$J ( x, p ) = J ^ { \mu } ( x ) p _ { \mu }, \quad \left \{ J, H \right \} = ( \nabla _ { \mu } J _ { \nu } ) \, p ^ { \mu } p ^ { \nu } = 0,$$

where (in a somewhat hybrid notation) the contravariant components of the momentum are p µ = ˙ x µ . Hence the covariant coefficient functions J µ form a Killing vector, a solution of the Killing equation

$$\nabla _ { \mu } J _ { \nu } + \nabla _ { \nu } J _ { \mu } = 0 \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad J ^ { \lambda } \frac { \partial g _ { \mu \nu } } { \partial x ^ { \lambda } } + \frac { \partial J ^ { \lambda } } { \partial x ^ { \mu } } \, g _ { \lambda \nu } + \frac { \partial J ^ { \lambda } } { \partial x ^ { \nu } } \, g _ { \mu \lambda } = 0. \quad \ \ ( 1 0 )$$

The second (contravariant) form of the equation states that the Lie-derivative of the metric w.r.t. the vector J µ vanishes, which is the usual definition of an isometry. Also note, that the constants of motion defined by Killing vectors are precisely those, for which

$$p \, \frac { \partial G } { \partial p } = G,$$

and therefore generates transformations under which the action is strictly invariant. This is to be expected for an isometry which by construction leaves the line element ds 2 = g µν dx dx µ ν invariant.

Although the coordinate transformations δx µ generated by Killing vectors thus have an elegant interpretation, this does not hold for the corresponding transformations of the canonical momenta p µ :

$$\delta p _ { \mu } = A _ { \mu } ^ { \nu } ( x ) p _ { \nu }, \quad A _ { \mu } ^ { \nu } = - \frac { \partial J ^ { \nu } } { \partial x ^ { \mu } }.$$

This transformation rule is not general covariant; as A ν µ ( x ) is point-dependent, covariance requires δp to be corrected for the parallel displacement generated by

the translation δx µ . Thus a set of covariant transformations in phase space is defined by

$$\Delta x ^ { \mu } = \delta x ^ { \mu }, \quad \Delta p _ { \mu } = \delta p _ { \mu } - \delta x ^ { \lambda } \Gamma _ { \lambda \mu } ^ { \ \nu } p _ { \nu }.$$

In order for these transformations to respect the Poisson brackets (2) and (3), it is then necessary to introduce a covariant derivative

$$\mathcal { D } _ { \mu } G = \frac { \partial G } { \partial x ^ { \mu } } + \Gamma _ { \mu \nu } ^ { \ \lambda } p _ { \lambda } \, \frac { \partial G } { \partial p _ { \nu } } = - \Delta p _ { \mu },$$

such that

$$\Delta G = \Delta x ^ { \mu } \mathcal { D } _ { \mu } G + \Delta p _ { \mu } \frac { \partial G } { \partial p _ { \mu } } = \{ G, G \} = 0,$$

and

$$\Delta H = \Delta x ^ { \mu } \mathcal { D } _ { \mu } H + \Delta p _ { \mu } \frac { \partial H } { \partial p _ { \mu } } = \{ H, G \} = - \frac { d G } { d \tau }.$$

Thus we have constructed a covariant expression for the Poisson bracket of two arbitrary scalar phase-space functions:

$$\{ G, K \} = \mathcal { D } _ { \mu } G \, \frac { \partial K } { \partial p _ { \mu } } - \frac { \partial G } { \partial p _ { \mu } } \, \mathcal { D } _ { \mu } K.$$

## 3 Killing tensors

The metric postulate guarantees that the geodesic hamiltonian (6) is covariantly constant:

$$\nabla _ { \lambda } g _ { \mu \nu } = 0 \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad \mathcal { D } H = 0.$$

The condition for a constant of geodesic motion then takes the simple form

$$\{ G, H \} = p ^ { \mu } \mathcal { D } _ { \mu } G = 0.$$

Applying this to a general expression of homogeneous rank n in the momenta

$$G ( x, p ) = G ^ { \mu _ { 1 } \dots \mu _ { n } } ( x ) p _ { \mu _ { 1 } } \dots p _ { \mu _ { n } } \quad \Rightarrow \quad p ^ { \mu } \mathcal { D } _ { \mu } G = \left ( \nabla _ { \mu _ { n + 1 } } G _ { \mu _ { 1 } \dots \mu _ { n } } \right ) p ^ { \mu _ { 1 } } \dots p ^ { \mu _ { n + 1 } }, \ \ ( 2 0 )$$

the condition for a constant of motion becomes a generalization of the Killing equation (10):

$$\nabla _ { ( \mu _ { n + 1 } } G _ { \mu _ { 1 } \dots \mu _ { n } ) } = 0.$$

The solutions of these equations are therefore known as Killing tensors [3, 4].

The geometrical interpretation of the transformations generated by constants of motion constructed from Killing tensors of rank 2 or higher, is more complicated than for Killing vectors. They do not generate transformations in the manifold, but in the tangent bundle, the physical phase-space:

$$\Delta x ^ { \mu } = \frac { \partial G } { \partial p _ { \mu } } = n G ^ { \mu \mu _ { 1 } \dots \mu _ { n - 1 } } p _ { \mu _ { 1 } } \dots p _ { \mu _ { n - 1 } },$$